An Archive within an Archive

Mamboury's Notebook

German Archaeological Institute Istanbul Online Exhibition

The main subject of this exhibition is one of Mamboury’s notebooks that we came across while digitizing the legacy of Wolfgang Müller-Wiener.

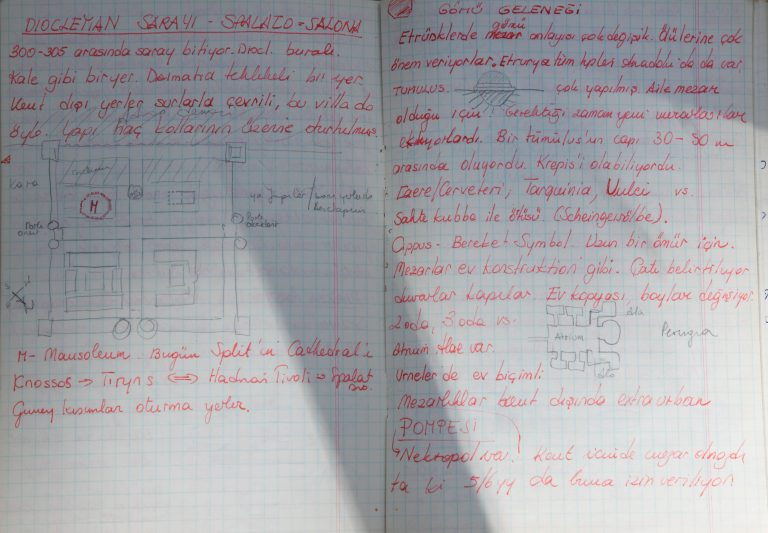

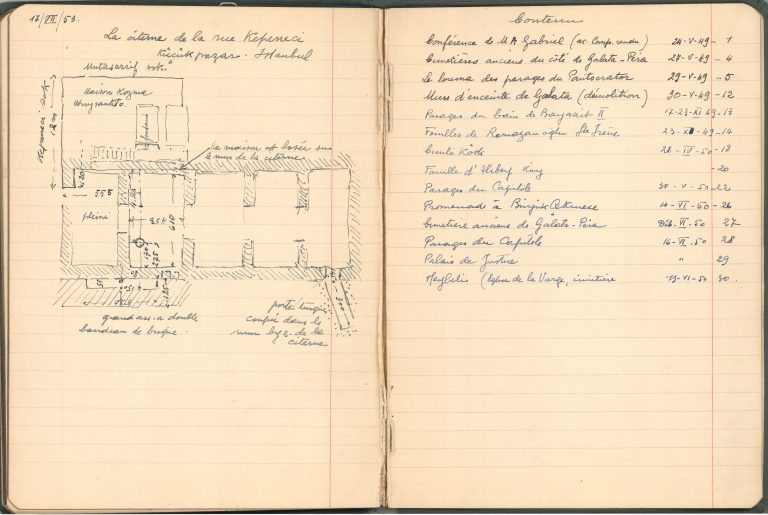

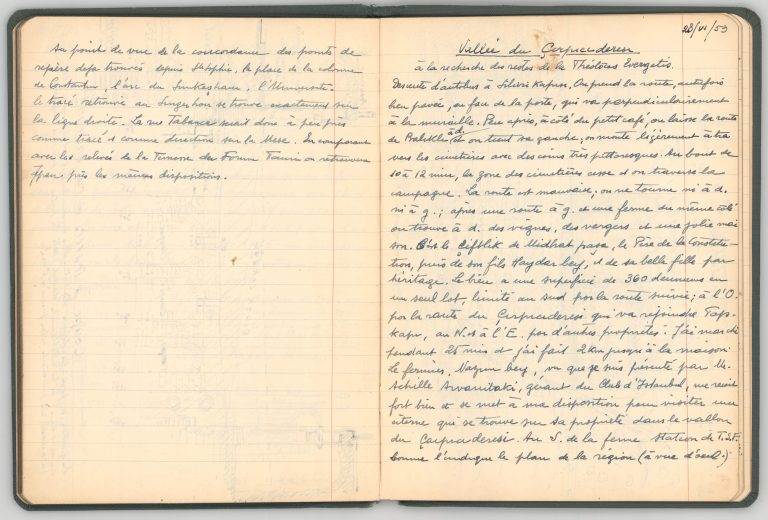

It is a relatively small notebook of 74 pages. It contains his handwritten notes in French and some very detailed drawings and sketches. It is an archive within an archive.

Recollections from Mamboury‘s Notebook

Müller-Wiener’s archive shows the background of his works and contains, among other things, his personal notes, drawings, maps, letters, scholarly articles, newspaper clippings and documents of the personal relationships that he forged in many years. Mamboury’s notebook is just one of the thousands of documents that formed a source for Müller-Wiener’s studies and publications. We do not have any evidence how this notebook reached Müller-Wiener. Perhaps he just took the notebook from the Mamboury archive at our institute, worked with it, and forgot to put it back. A Turkish postage stamp which is kept in the notebook may be a tiny clue that the notebook might have been sent to Müller-Wiener by somebody else. We know that Müller-Wiener like an archivist never kept anything for no reason and never put two unrelated things side by side.

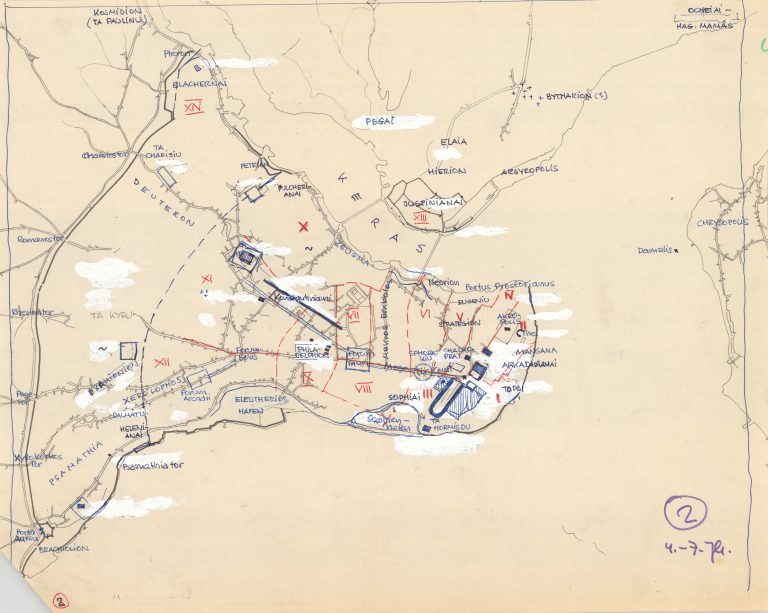

Müller-Wiener, like Mamboury, devoted a significant part of his works to Istanbul’s historical heritage. Right after he was appointed director of the Istanbul Branch of the German Archaeological Institute in 1975, beside all his archaeological works he rolled up his sleeves to complete his two major works: Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn des 17. Jahrhunderts (1977) and Die Häfen von Byzantion, Konstantinupolis (1994).

There are many documents in the Müller-Wiener archive showing the background of his book Die Häfen von Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul.

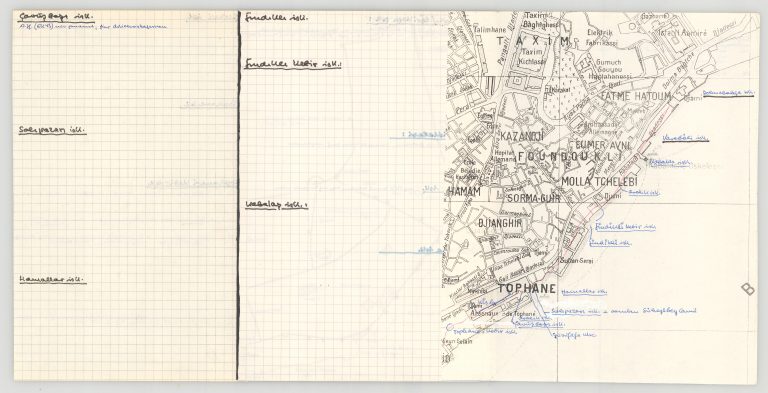

This sheet shows how Müller-Wiener studied the coastline of Istanbul, stretching from Tophane to Beşiktaş. Left side of the page is reserved for further notes

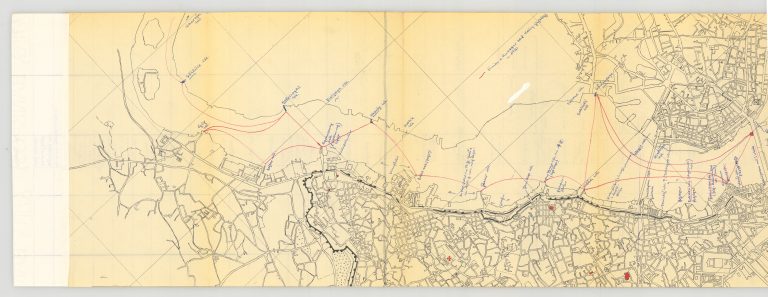

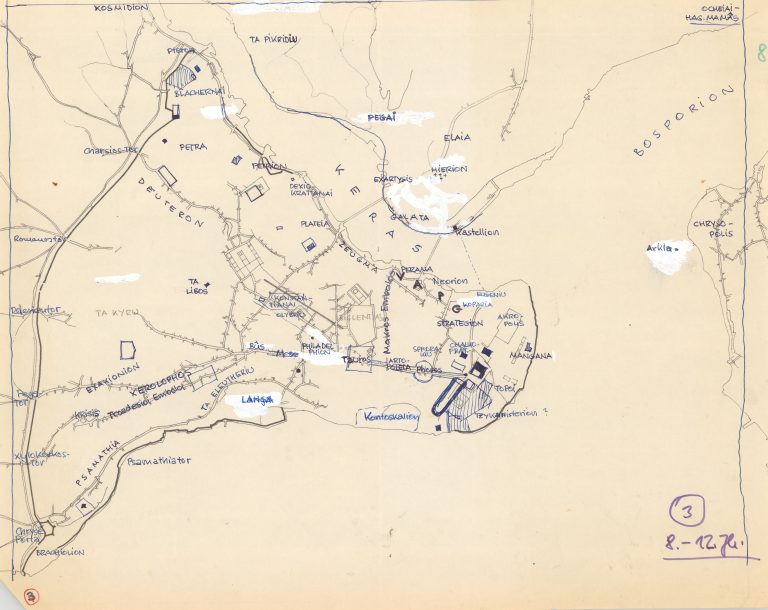

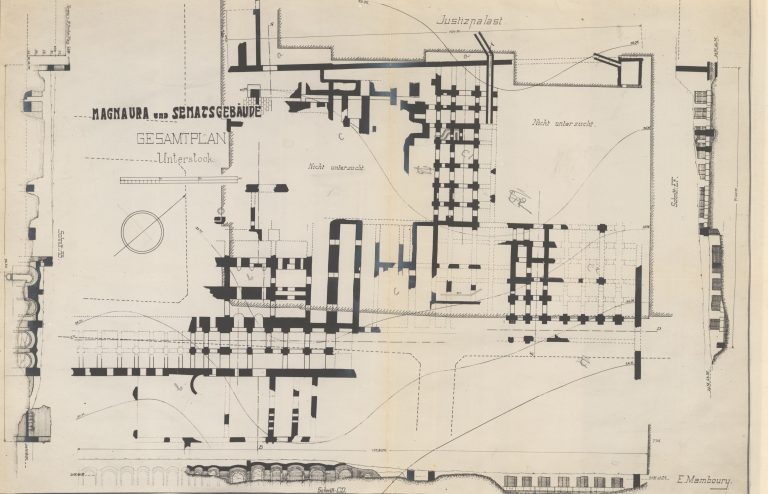

For his book Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls, Müller-Wiener used numerous sources to design new historical maps. The documents from his legacy show this multi-layered work of collecting and organising information, which Müller Wiener as an architect often accomplished in the form of drawings and sketches.

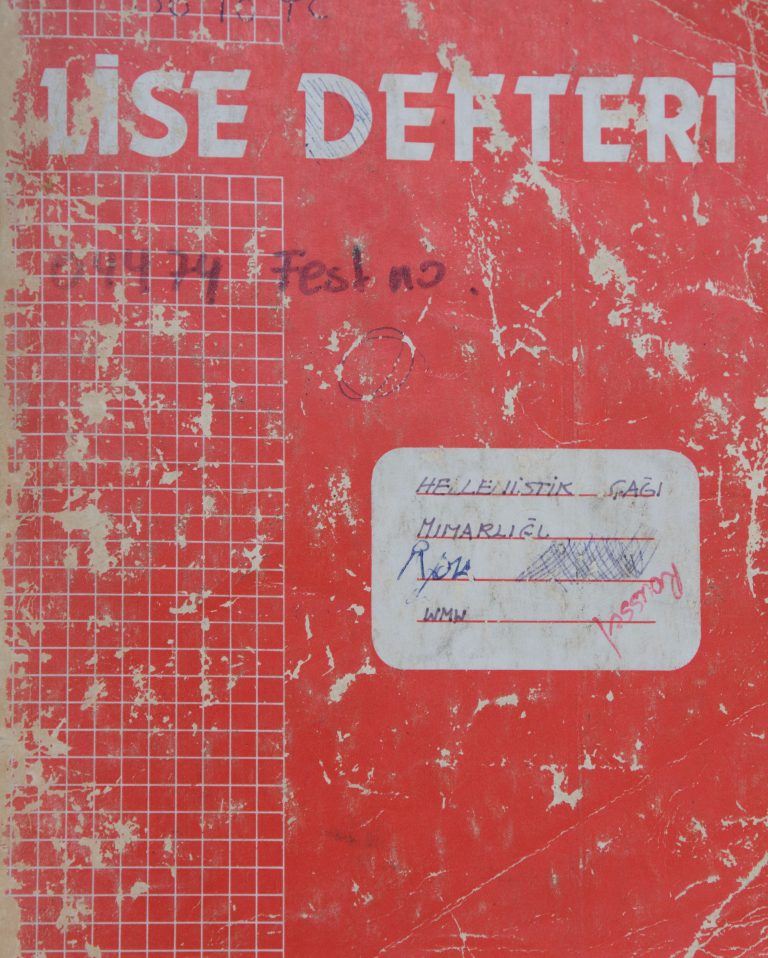

Like Mamboury, Müller-Wiener taught architectural history at Istanbul University in the Department of Classical Archaeology between 1976-1986.

Zeynep Kuban is a professor of the history of architecture at the Istanbul Technical University. She had attended the lectures of Müller-Wiener. She says she switched from archaeology to the history of architecture thanks to him, and narrates her encounters with Müller-Wiener:

“He used to give his lessons in Turkish. He was lucky in our class, because that year were many students who spoke German. When he couldn’t find the proper Turkish words we helped him. I remember one example that made us smile. While describing the Ionian column, he said blonde instead of thin and tall.

One day I went to Priene with a group of students in the late 1980s, and as I was wandering around the Athena temple, I saw him drawing some blocks and he said: “Was machen Sie denn hier?” Many years after this encounter, when I visited the same place again I found a measure angle from steel that Müwie (as we called him informally) had probably dropped. The steel angle remained there between the blocks for a long time even after Müwie already had passed away. Each spring when we came to Priene with the students and I saw it, I felt he was greeting me.”

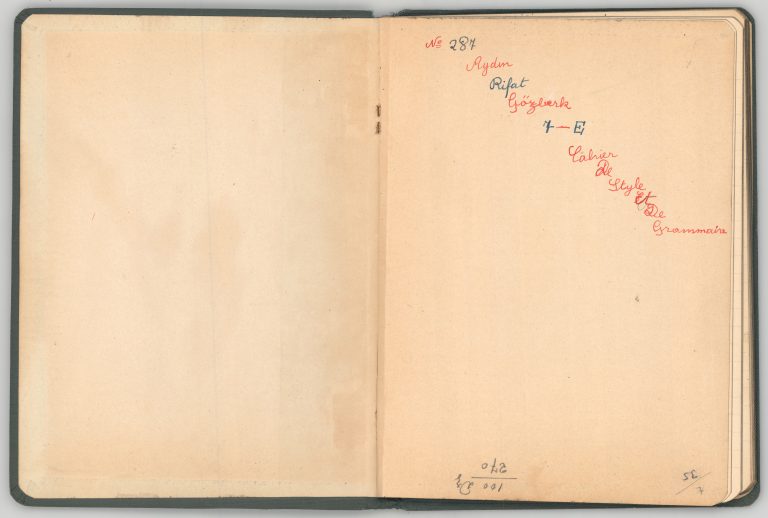

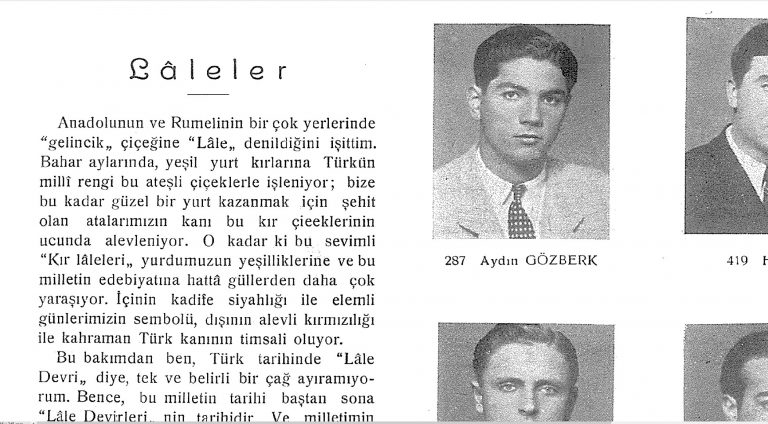

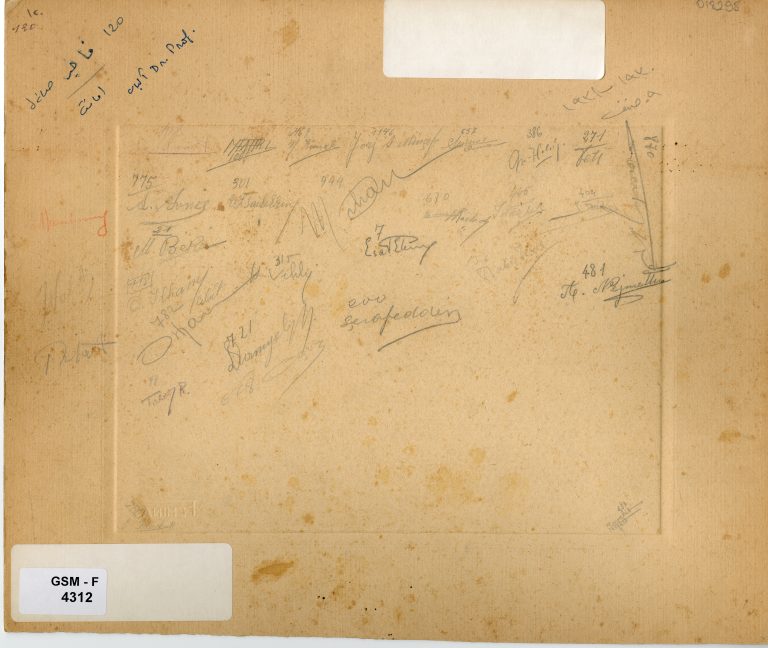

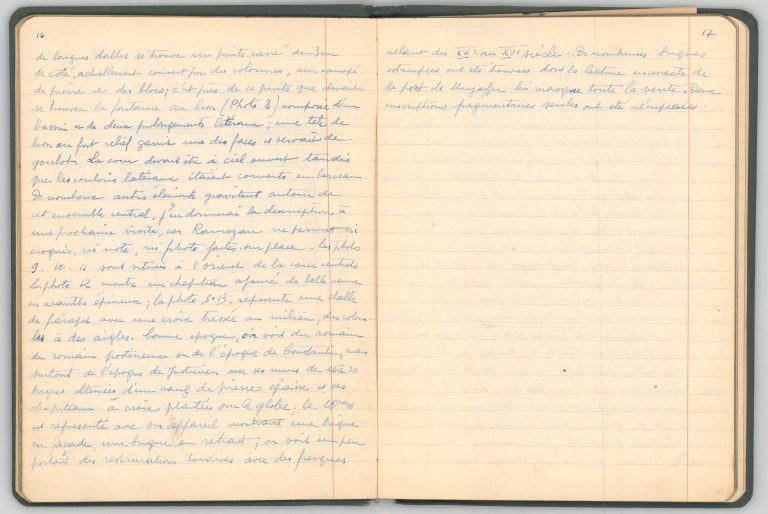

This notebook, which presents a just small part of Mamboury’s extensive works on Istanbul, is also a reminder from the years he was a teacher at Galatasaray High School. When we examined the physical condition of the notebook, we discovered that the first owner of the notebook was a certain Aydın Rıfat Gözberk, a student at Galatasaray High School in the class 7E. He was also in the student club of philosophy. It is obvious that Aydın used the notebook for his French grammar lessons for a while. Later that notebook reached Mamboury in some way. After carefully cutting the pages on which Aydın may have taken his notes, Mamboury reused the notebook by starting to write from the back. Maybe these notes which we do not have now since they were carefully cut, may have been written by Aydın during the French lessons that Mamboury taught; who knows… Aydin graduated from Galatasaray High School in 1944. And Mamboury retired from Galatasaray High School, where he had started teaching in 1923, in 1949 or 1951.

Mamboury‘s Notebook

The contents of Mamboury’s notebook can be listed, briefly, as follows:

His review of Albert Gabriel’s conference on Bursa at Istanbul University, his observations on old tombs in Galata and Pera, his observations on the Pantokrator Church (Zeyrek Camii), his notes on Galata fortification walls that were intended to be demolished to make room for a parking lot, detailed drawings of the Hippodrome, a historical bath in Bayezid Square and the Ibrahim Pasha Palace, notes on Hagia Eirene excavations, news about the restoration of Ҫiniliköşk, his visit to Alibeyköy excavations, his Büyükçekmece tour, and notes on a trip to a Byzantine church in Heybeliada.

Archaeological and Historical Diary,

by E. Mamboury

Istanbul

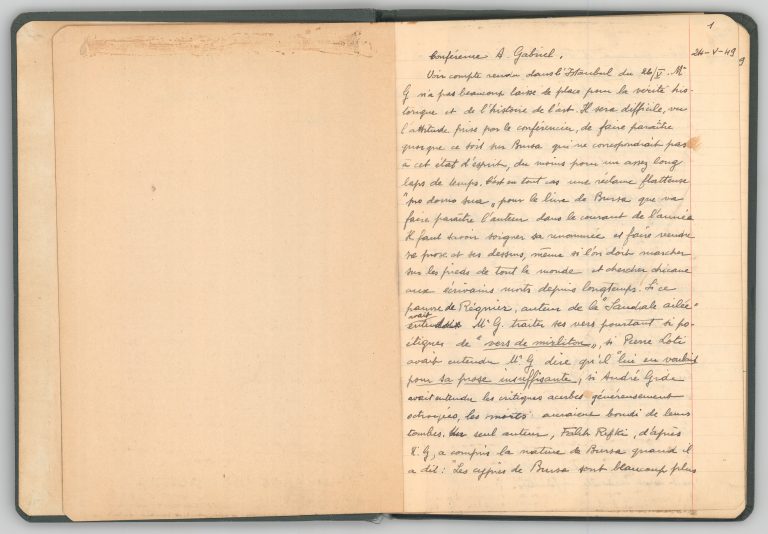

Conference of A. Gabriel, 24 May 1949

Albert Gabriel’s conference on Bursa at Istanbul University obviously upsets Mamboury a little. His notebook includes many archaeological and historical details, but the first two pages are the most passionate account where Mamboury half-mockingly criticizes Albert Gabriel:

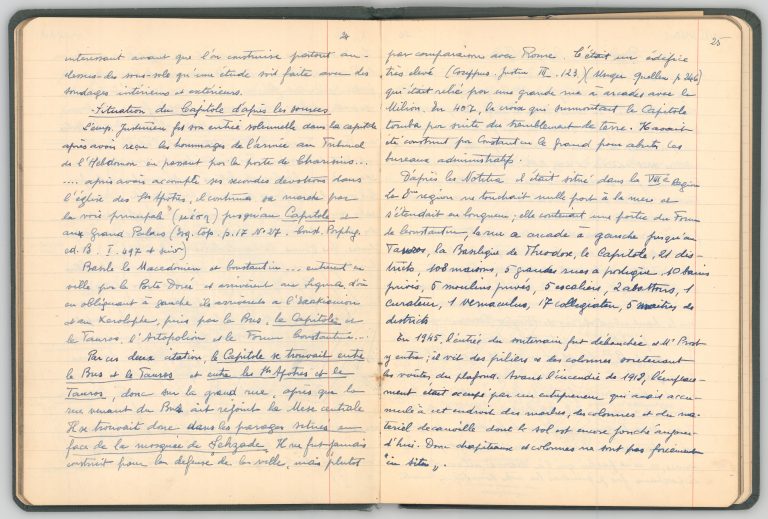

“At this eloquent conference, enriched by colourful slides, we were able to experience the author’s extraordinary talent for documentation. When he spoke about the mihrab of the Yeşil Mosque, which contains the names of the ceramic masters, he had no doubt that they were from Tebriz, because on the right pillar it says ›üstadan-e Tebriz‹ (masters from Tebriz). ′Nevertheless′ he added, ′who knows how many Turks have spread all over Eastern Anatolia, so we can believe that these masters were Turks.′ We can take our hats off to him, for it could not have been explained better. It is a good example of flattery and sycophancy. But I doubt if the Turks, who have common sense and know their way around, would take this bold claim seriously.”

Nevertheless the writer of a newspaper article about the same conference disagrees with Mamboury. Apparently Mamboury clipped the newspaper article and stored it in his diary. According to the article, the conference hall was crowded with Turkish and French students although the weather was too hot. Albert Gabriel was speaking without looking his notes. Buildings and landscape of Bursa were presented with colourful slides and his remarks below were acclaimed in the hall:

“First of all we have to debunk certain ideas, which are entertained in the West and are still generally accepted, like Turks did not play a role in the design and construction of their buildings during the foundation period of the Ottoman Empire. If we study history and observe the intellectual and social environment we can see that these opinions are false. When I directly examined Ottoman buildings I came to agree with the ideas of my esteemed friend Fuad Köprülü, who perfectly demonstrated that the origins of the Ottoman Empire cannot be reduced to a simple scheme that argues that the conquerors made use only of Byzantine institutions. We now better understand the situation of Anatolia, and the role played by the religious mystics and guilds at that time thanks to the efforts of this orientalist scholar. Archaeological studies also strengthen certain hypotheses which, underlining continuity, link the beginning of the Ottoman art to the Seljukid art.”

Mamboury writes the date of this French article as “Istanbul, 26 Mai 1949”. The passionate tone in his notes in the diary may indicate that he was also present at the conference.

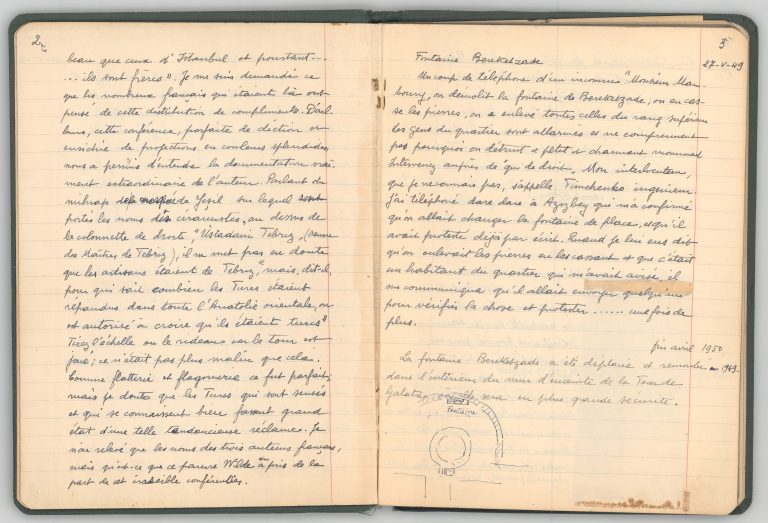

Bereketzade Fountain, 27 May 1949

This page begins with exciting news:

“Received a phone call from a stranger: ′Mr. Mamboury they are demolishing the Bereketzade Fountain, or breaking its stones. They have already removed the stones in the upper row. The inhabitants of the neighbourhood are alarmed and they do not understand why this small and charming monument is being destroyed. Please intervene in the situation by talking to the authorities.′

Later he learned that the person who called him was a certain Timchenko, an engineer.

“I immediately telephoned to Aziz Bey and he told me that they were moving the fountain to another place, and that he protested it in writing. When I told him that an inhabitant of the neighbourhood called me and informed me that they were breaking the stones, he said that he would send a man to check the current situation, and protest once more.”

Mamboury follows the fate of the fountain; one year later he recorded:

End of April, 1950

»The Bereketzade Fountain was moved and rebuilt inside the walls of the Galata Tower in 1949. It will be more secure there.“

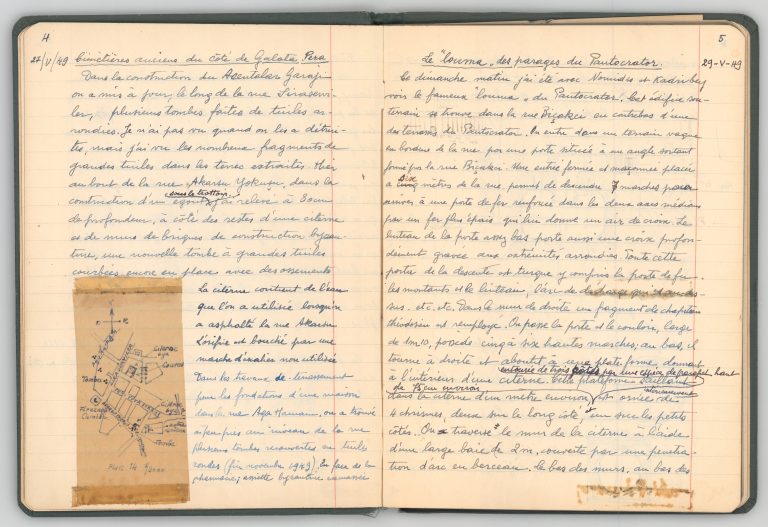

Old graveyards on the side of Galata-Pera, 27 May 1949

Mamboury rushes to Galata, after the phone call from Timchenko. He writes in this page that he finds many ruined graves in a construction site. Apparently the construction workers destroyed the graves before Mamboury reached the site and it seems there was a graveyard there once:

“Yesterday, during the construction of a sewer at the end of Akarsu Yokuşu street, I came across a new grave with large curved tiles, bones still in it. It was under the sidewalk and 80 cm deep, and next to the remains of a cistern and those of the brick walls of Byzantine construction. The water in the cistern was used in the asphalting Akarsu Street. The hole is blocked by an unused stair step. Several other graves with Roman tiles were found at approximately street level at the foundation of a house in Ağa Hamamı Street (end of November, 1949). Opposite of the chemist’s in the neighbourhood some Byzantine plates were discovered.”

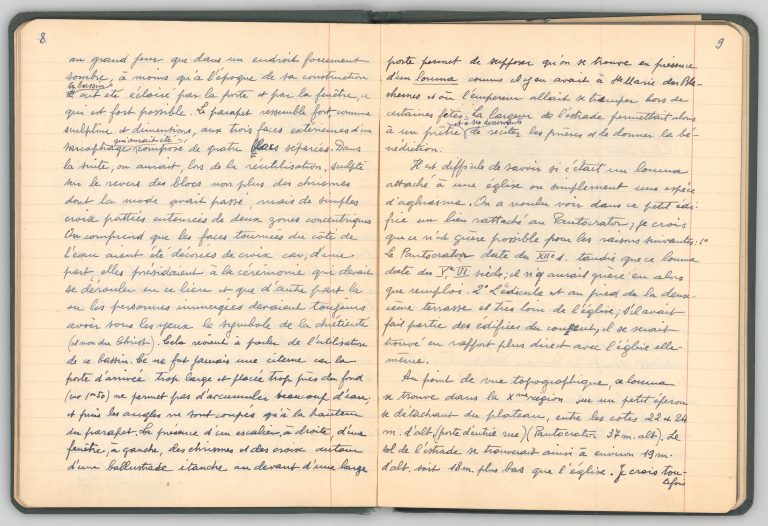

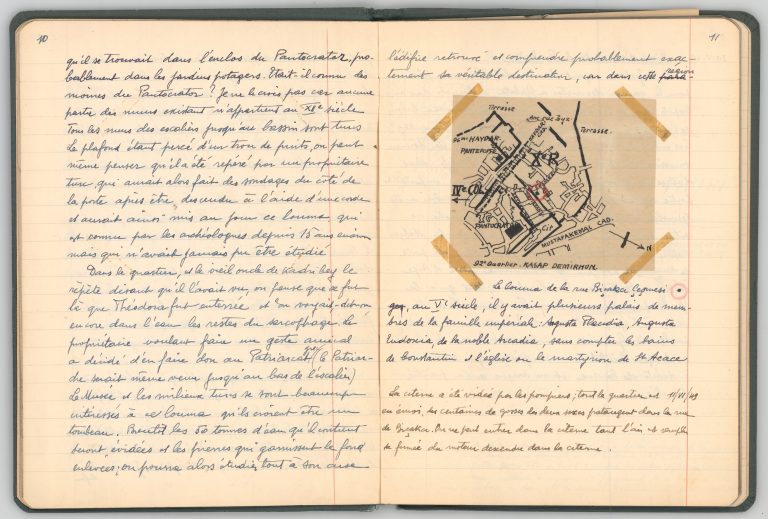

“Louma“ Near Pantocrator, 29 May 1949

A Sunday morning. Mamboury goes to see the famous louma of Pantocrator together with Nomidis Bey and Kadri Bey. They enter the louma through an iron door below a staircase. It is situated on Bıçakçı Road, under one of the terraces of Pantocrator. When they slightly bend down at the narrow door something draws Mamboury’s attention:

“On the rather low door lintel is a deeply engraved cross with rounded ends.”

Although a fragment of a column capital belonging to the Theodosian Period can be seen on the wall on the right, according to Mamboury, the entire entrance section, including the iron door, was made by the Turks.

“We pass the door and proceed through the corridor, which is 1,10 m wide; there are five-six high steps and below it turns right and ends up in a platform looking inside a cistern.”

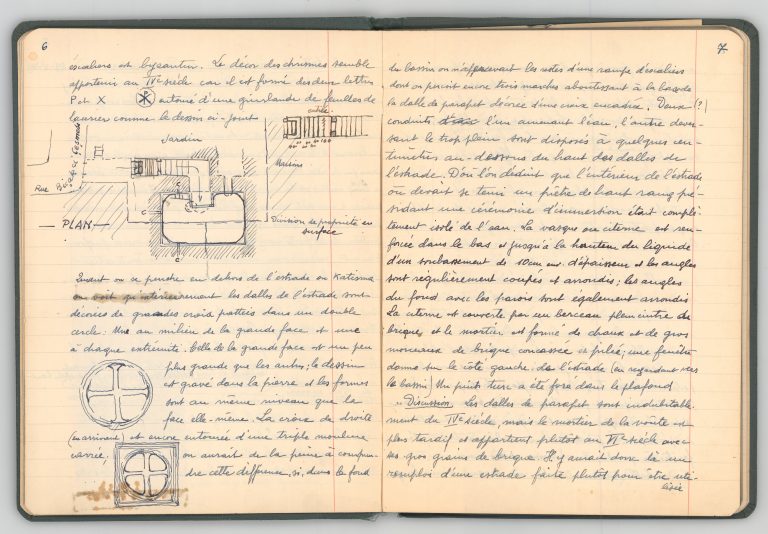

Inside the cistern they see a platform enclosed by a balustrade on which are four christograms. It is a combination of Greek letters X and P, adorned with laurels. Mamboury thinks these are from the 4th century, judging by the shape of the laurels. He draws small sketches of these christograms in his diary. There is also a podium or a kathisma, and when he leans out of it he sees large crosses engraved on the slabs of the platform. He draws a sketch of these crosses as well. They also find two water conduits at the slabs of the platform; one is bringing the water in, the other discharging the overflow. This discovery leads Mamboury to interpret for certain that this is a place where baptism with full immersion once took place.

His description of the structure of the louma near the Pantocrator is the most extensive part of his diary. Yet his notes are sometimes ambiguous and patchy. He names, for instance, what he describes before as cistern, as a pool or sarcophagus this time. Mamboury starts a rhetorical discussion:

“Discussion: The slabs of the balustrade are without doubt from the 4th century, but the brick works and the mortar of the vault can be dated to a later period, to the 6th century.”

After a lengthy consideration Mamboury decides that this place is actually a baptistery.

“The presence of a staircase on the right and a window on the left, and that of the christograms and crosses around a watertight balustrade in front of a large door leads us to suppose that we are in a louma; like the one at the Church of the Virgin Mary of Blachernae, in which Byzantine emperors, at certain feasts, immersed themselves. The width of the podium (or the kathisma) would allow a priest and his subordinates to recite the prayers and give the blessing.”

Mamboury and his friends wonder whether there was a connection between this small structure and the monastery of Pantocrator. Might this louma have been a part of the monastery? Mamboury does not think so, and he explains his reasons:

“The Pantocrator is dated to the 12th century, but this louma is from the 5th to 6th centuries. There cannot be a connection, but the louma was just reused at a later time.

The Aedicula is at the lower levels of the second terrace, hence it is far away from the Pantocrator. Had it been one of the parts of it then a connection would have been supposed.”

As it is far from the Pantocrator, nevertheless it is still inside the boundaries of the monastery. He remarks in his diary:

“I assume, however, that the louma was inside the enclosure of the monastery, probably in the part of the fruit and vegetable gardens. Did the monks of the Pantocrator know its existence? I do not think so.”

Mamboury visits the same louma 13 days later again.

11 June 1949

This time Mamboury writes about a sarcophagus in the water. Yet this sarcophagus is actually the baptistery that he mentions a couple of paragraphs above. It is understood from his writings that the plot of land which also includes the louma actually belongs to a private owner. The person who owns the land decides, as a gesture of goodwill, to donate the sarcophagus to the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Unfortunately we do not know whether the Patriarch visited the place or the sarcophagus was donated. There are not further notes in the diary about this donation and its consequences.

“The Istanbul Museum Administration and the Turks are very interested in this louma which they believe also includes an imperial graveyard. 50 tons of water that it contains will be emptied and the stones at the bottom will be removed, and then we can study the foundation of the structure easily and probably understand the real purpose of usage of this place for certain. There were palaces of the members of the imperial families of the 5th century, here in Bıçakçı Çeşmesi street.“

11 June 1949

For the same day he records that:

“The fire brigade started to discharge the water. All the children in the neighbourhood invade Bıçakçı Street to have fun. We cannot go into the cistern. Air is full of smoke coming from the engines“

These are the last entries that the Mamboury’s notebook has under this heading.

Galata Walls, 30 May 1949

Mamboury is especially interested in brick stamps as well. Maybe that’s why he visits Galata quarter so often where he, occasionally, finds bricks from graves. He passes the demolished parts of the Genoese walls:

“Coming from Karaköy following Gümrük street and turning to Mumhane street, I was walking along the Genoese walls which are on the right hand side of the street and I arrived at the demolished part of the walls.”

We understand from the notes that there was nothing left to do but describe the location of the wall.

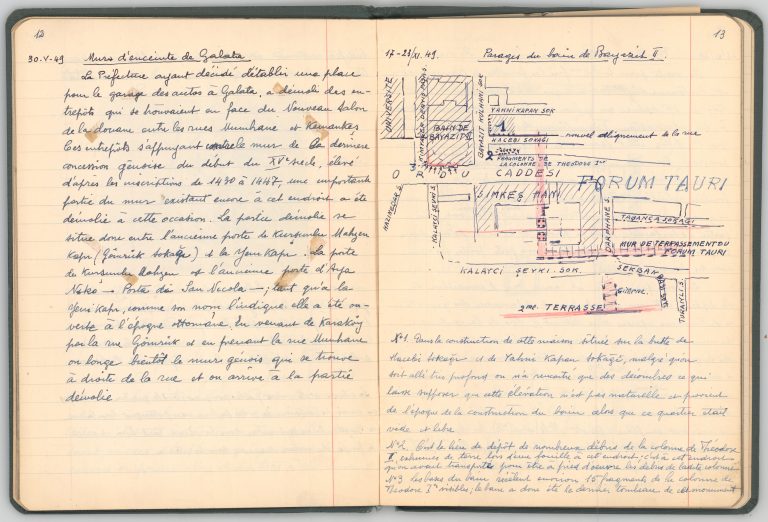

Area around the Bayezid Bath, 17-23 November 1949

Mamboury documents in his diary the multi-layered structure of the site. It seems pieces of the column of Thedosius I had been excavated once and piled up. Now these column pieces have come to light again and with them the remains of the bath. Mamboury remarks:

“The basement of the bath contains some 15 fragments of the Column of Theodosius I; therefore we can assume that the bath is the last grave of the monument.”

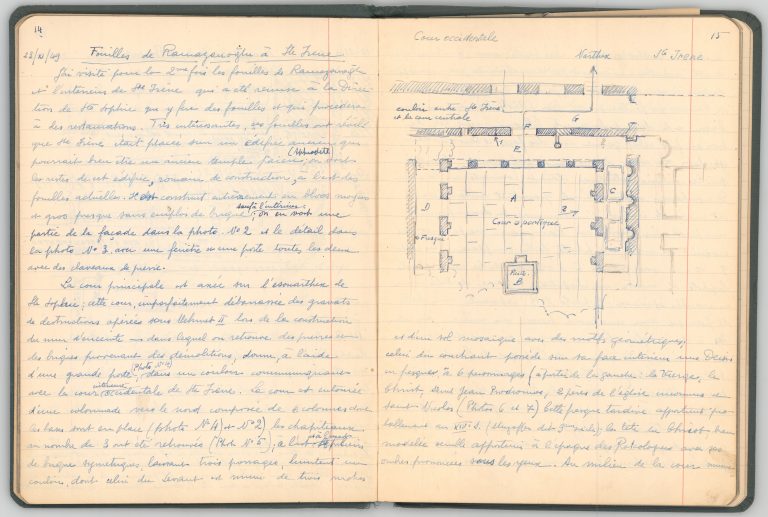

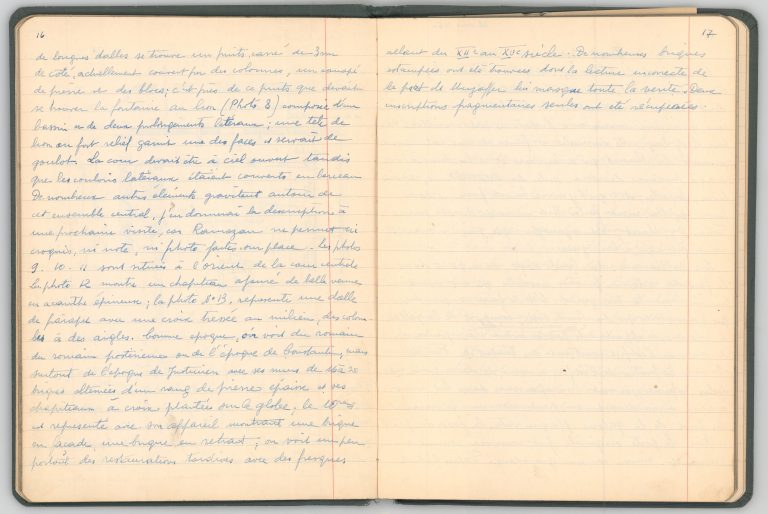

Excavation by Ramazanoğlu of Hagia Eirene, 23 November 1949

According to his diary Mamboury visited the excavation of Hagia Eirene, after he had seen the area of the Bayezid Bath at the same day. The excavation director is the museum archaeologist Mr. Ramazanoğlu. Mamboury is excited to see that a pagan temple was found under Hagia Eirene. He notes that there is a courtyard with a big gate, debris had been cleaned, which faces a corridor towards the inner western courtyard of the church, four columns in the courtyard with the big gate, three column capitals and a deesis fresco with six persons: Virgin Mary, Christ, St. John the Baptist, two unidentified priests and St. Nicholas. Ramazanoğlu dates the fresco to the 9th century but Mamboury thinks it is from the 14th century. Apparently there is a great tension between them:

“Ramazanoğlu does not allow me to take pictures in the excavation site; he even doesn’t let me to take notes and draw sketches.”

Ramazanoğlu was evidently unfriendly to Mamboury. Nevertheless Mamboury managed to take photographs and drew a plan of what he observed. He even decided to visit the site again. He writes the unfriendly behavior of Ramazanoğlu’s in his diary, with resentment:

“Many brick stamps were found, but the incorrect reading of them by Muzaffer [Ramazanoğlu] obscured the whole truth. Only two fragments with inscriptions were taken and stored.”

After this entry Mamboury does not write in his diary for five months.

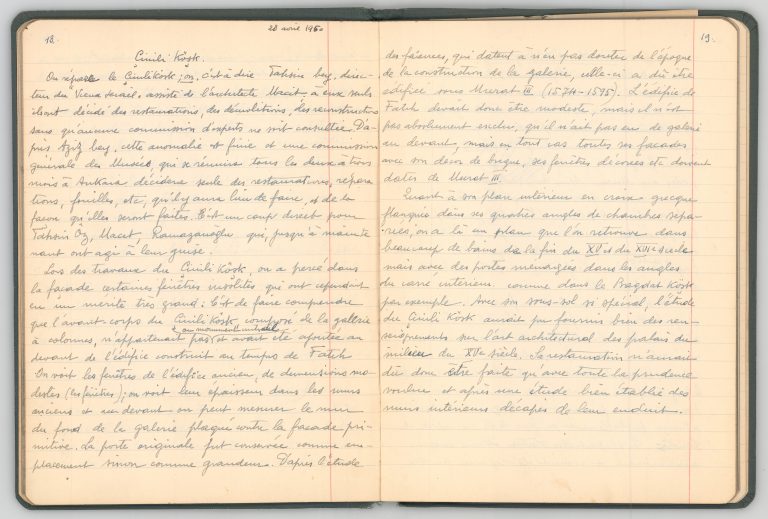

Çinili Köşk, 28 April 1950

Although there were some problems with the museum staff in the excavation site, this time Mamboury is inside the museum.

“Çinili Köşk is being repaired; I mean Tahsin Bey, director of the ’Old Palace’, assisted by the architect Macit decide alone the restorations, demolitions, and reconstructions without consulting any commission of experts. But Aziz Bey says this anomaly should be over and a general commission of museums, which will meet every two or three months in Ankara, will alone decide on the restorations, repairs, excavations, etc.; this is the right thing and this is how the things should be done. It is a direct blow to Tahsin Öz, Macit, and Ramazanoğlu who, until now, have done what they wanted.”

Despite his angry words Mamboury also notes his positive views about the repair works. He likes very much that certain windows on the façade of the building, which remained blocked so far, were uncovered. He emphasises that the restoration works should be done after the building is examined carefully. This statement shows his modern understanding of restoration.

Excavations at Alibeyköy

Mamboury visits this enclave because of illegal house-building activities in the neighbourhood. Istanbul Archaeological Museums directed a rescue excavation in the district between 1949 and 1950, and a group of famous statues called Silahtaraga that were found during the excavations were exhibited in the museums. Mamboury lists the finds:

“After their restorations we noticed Artemis, without head and arm. A torso of Neptune (Poseidon), Apollo without arms and feet, a nymph without head and arms, parts of Nike, parts of legs and arms belonging to a statute of a child, and part of a head of a statue of a dog.”

Mamboury thinks this place is the “Altar of Semystra”. He also mentions that there was a Byzantine necropolis there.

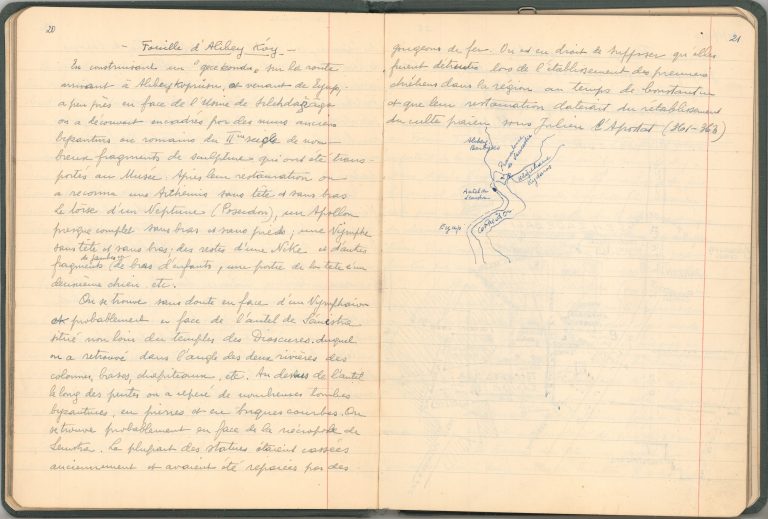

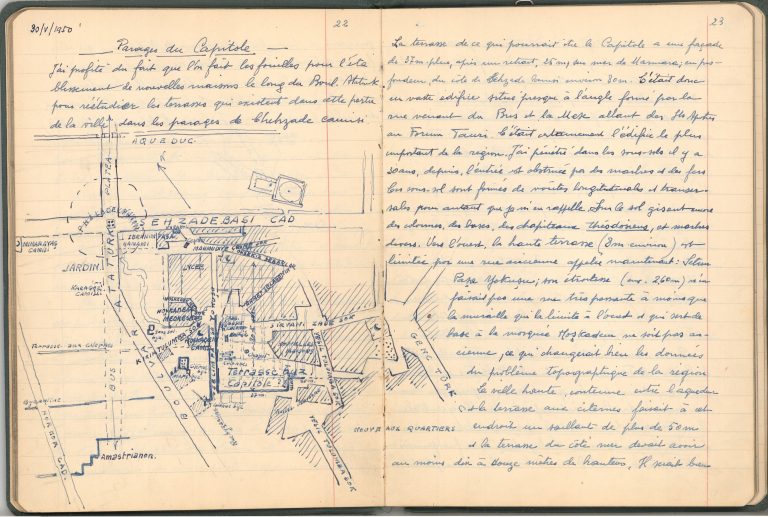

Capitol Area, 30 May 1950

Intensive construction activities around the newly opened Atatürk Boulevard create a study area for Mamboury. He revisits the basement of a building, where he had been thirty years ago for the first time. He enters the premises by passing the doorway which is blocked by randomly placed marbles and iron. He finds the place as it was thirty years ago:

“There are still columns and slabs, and column capitals of Theodosius and various marbles.”

He did what he could; writes and draws in his notebook what he observes:

“The facade of the terrace that may have belonged to the Capitol is more than 37 m long. 25 m of which is over the sea level. It is around 80 m. deep around the Şehzade Mosque. This may indicate that it was once a large site at the intersection of Mese and the road that stretching from the Church of Holy Apostles towards the Forum Tauri. It was beyond doubt the most important structure in the area.”

He thinks exploratory drilling should have been done before building activity started on top of the structure. He needs to read in order to fully understand what he observes and writes a new title in his notebook: “The Situation of Capitol according to the Sources.” He notes his readings from ancient sources and his interpretations.

A Tour around Büyükçekmece, 4 June 1950

Mamboury started to study the Çekmece region in 1930s. Moreover he identified the region as Rhegion, as mentioned by ancient sources. We understand from his notes that he visits the area this time for just sightseeing: “I will take more detailed touristic notes next time.”

His tour starts with a car then he continues on a donkey’s back. He sees various ruins which he thinks might have been religious structures. We don’t know whether these belong to the ancient city of Bathonea. Mamboury is still impressed by the area although he often visits the place.

“Culture is various and pretty good. We pass through places date back to a couple of millennia.”

And he rejects the assumption that Sinan was the architect of a bridge there:

“Two long inscriptions at the entrance of the bridge indicate that Sinan couldn’t have been the architect of this bridge.“

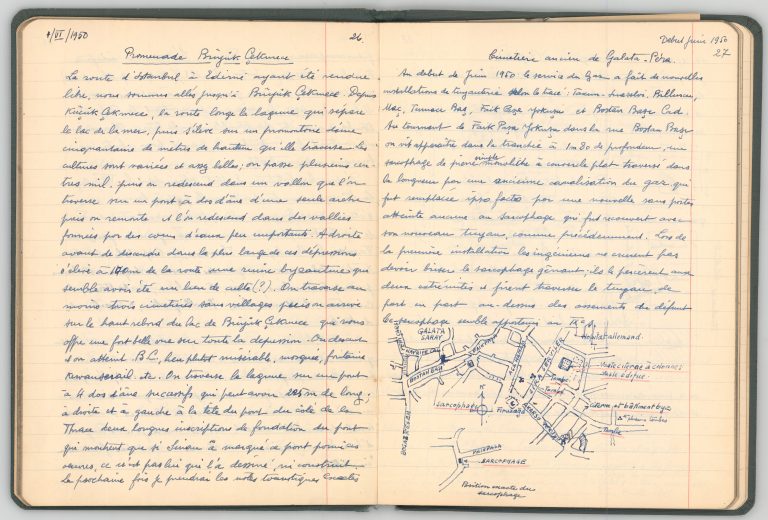

Old Graveyards of Galata-Pera, June 1950

This time Mamboury strolls through different streets of Galata. Engineers are about to install gas pipeline. During the digging a sarcophagus is found in 1,80 m deep in Bostanbaşı street. Carved out of one-piece plain stone, this unfortunate sarcophagus is about to suffer yet another pipeline operation:

“During the first installation, the engineers did not think about the sarcophagus, drilled the stone at both ends and placed the pipeline through the sarcophagus; just above the bones of the deceased. This sarcophagus seems to belong to the 9th century.“

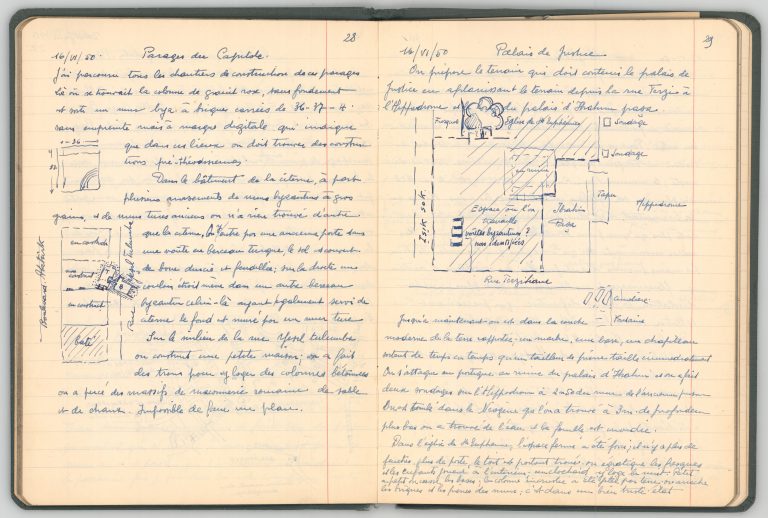

Capitol Area, 16 June 1950

Mamboury is in the Şehzade Mosque area again, one month after his last visit. We understand from his notes that he came here often but he didn’t take notes every time:

“I visited all the construction sites in the area.”

He arrives at a place which he calls cistern. He measures bricks (without stamps) and notes his measurements: 36/37/4. Byzantine and Ottoman walls mixed together. He tries to analyse the walls and the mortar. Above his head are holes that were drilled to place the concrete pillars of a house:

“Countless Byzantine walls of sand and limestone were pierced. It is impossible to draw a plan of the site.”

Palace of Justice, 16 June 1950

Mamboury witnesses the construction of the Palace of Justice. The area just behind the Palace of Ibrahim Paşa is being levelled:

“Whenever marbles, bases and column capitals surface a stonemason cuts them immediately.”

The Church of St. Euphemia has its share of these wild construction activities:

“The closed space inside the Church of St. Euphemia was broken in; there are no windows or doors. The roof was drilled and the frescoes were scraped. Children play inside in the morning and a certain tramp stays there at night. They slowly break the floor; an encrusted column was thrown to the ground, and the bricks and stones were torn from the walls. It is in a very gloomy state.”

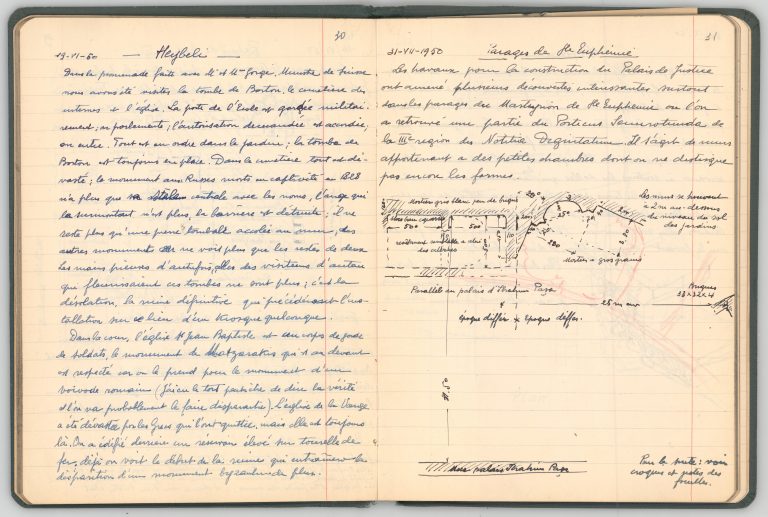

Island of Heybeli, 19 June 1950

Mamboury’s sadness continues. He visits the island of Heybeli along with the Swiss consul, Mr. Forge and his wife. They are allowed to enter the military school there. They see the graveyard and the Monastery of St. John the Baptist inside the premises. The graveyard is in a sad condition.

In the face of the remains of the chapel of St. Mary surmounted by modern construction he summarized:

“Behind it, a water reservoir was built on an iron tower, indicating the beginning of the disappearance of another Byzantine monument.”

The Area of St. Euphemia, 31 July 1950

Mamboury seems to recover from the shock of his first visit to the Hippodrome:

“Several interesting discoveries were made during the work for the construction of the Palace of Justice. In the vicinity of the Martyrion of St. Euphemia, parts of the Porticus Semirotunda in the III. Region, about which are information in the Notitia Dignitatum, were found. There are walls belonging to small rooms whose shapes we are unable to distinguish.”

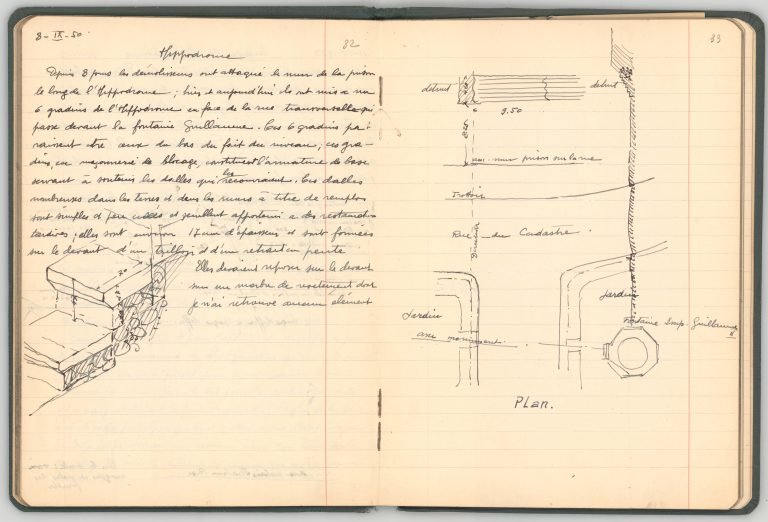

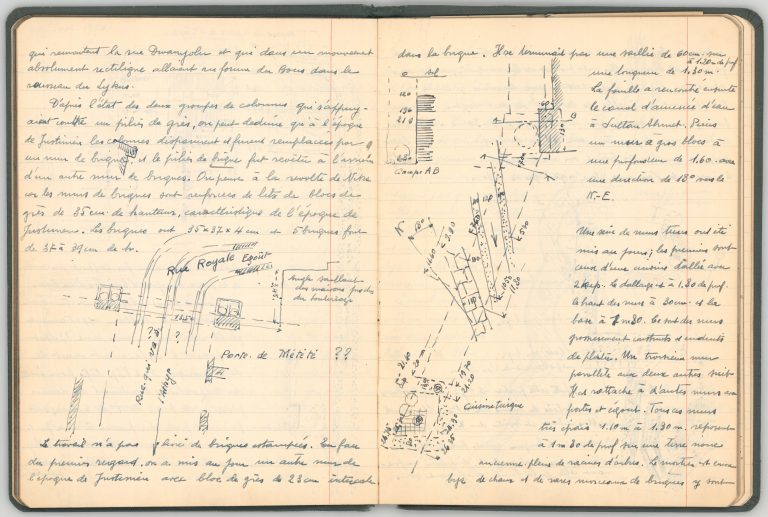

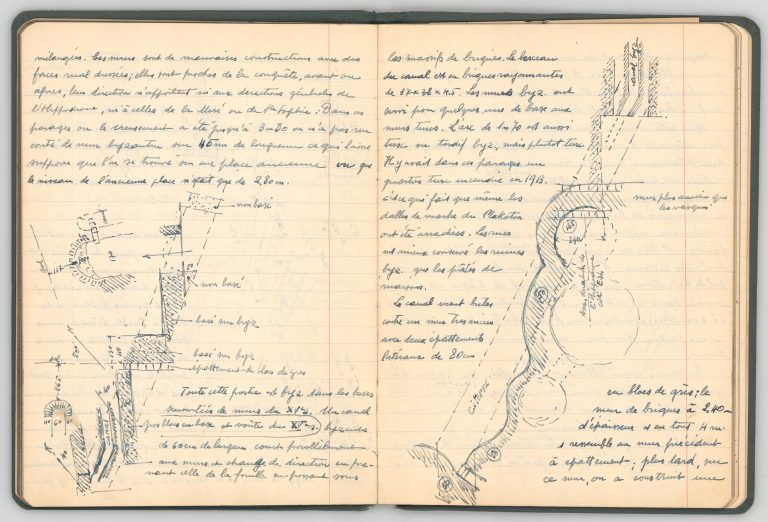

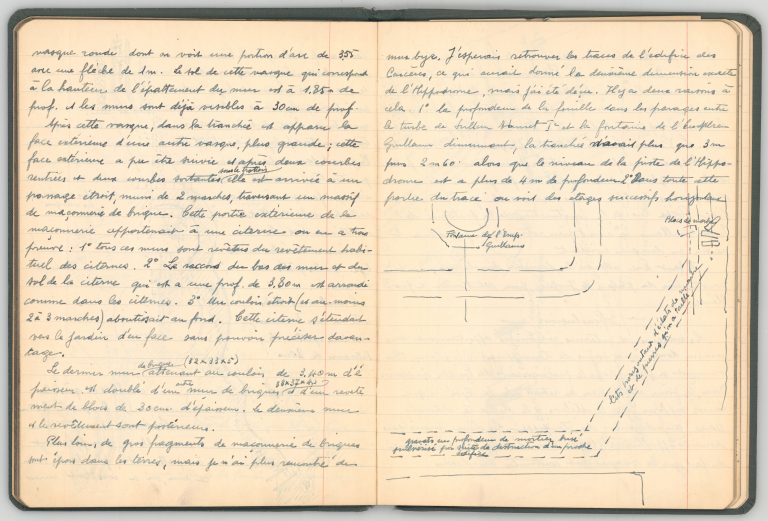

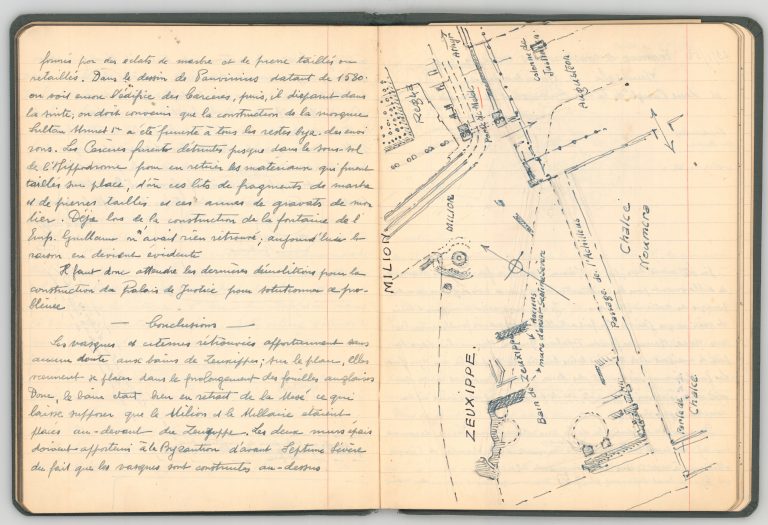

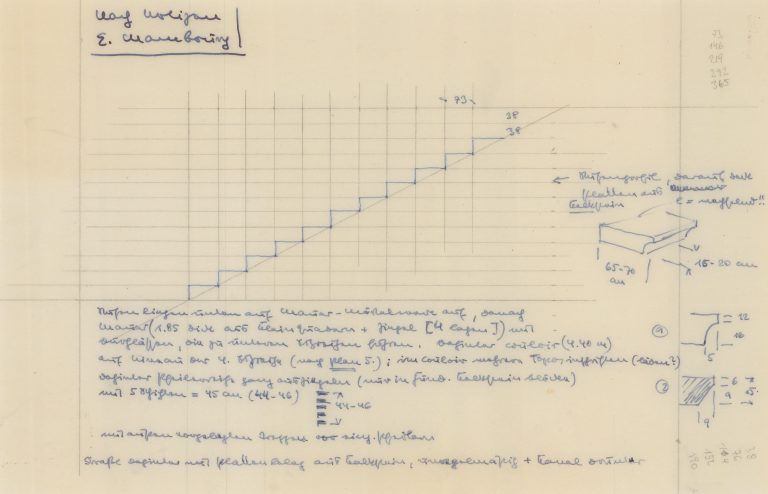

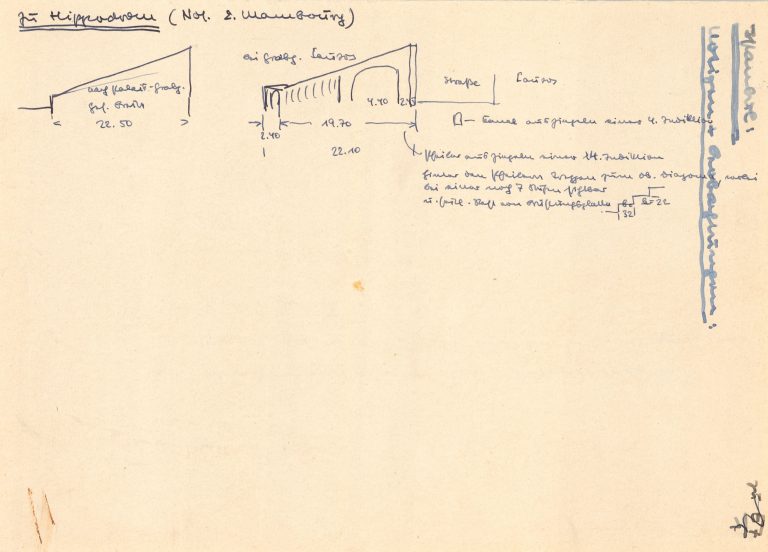

Hippodrome, 8 September 1950

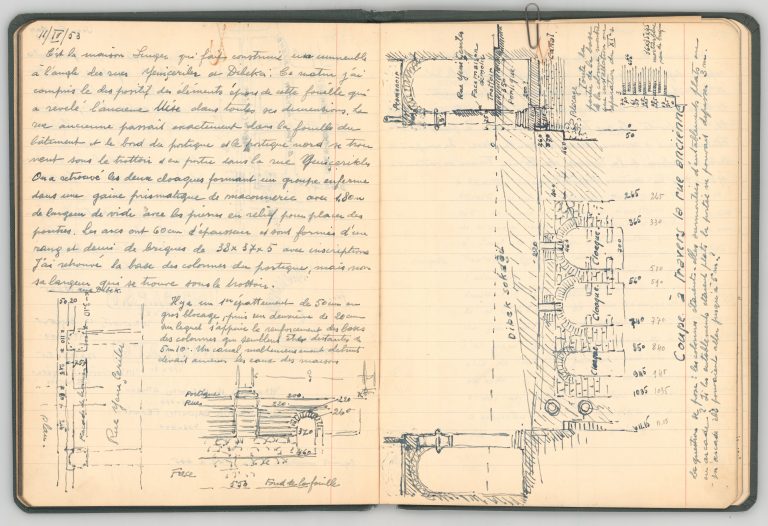

Mamboury reserves the rest of his notebook for the excavation in the Hippodrome (except two headings). Background of the Mamboury’ notes are his excavation along with the principal of the French School in Athens R. Demangel in the eastern sector of the Topkapı Palace between 1921 and 1923, and another excavation along with Theodor Wiegand (director of the Antiquities Department of the Berlin Museums) in the Hippodrome in 1918 and 1932. This time he visits the area because of the new excavations carried out by Rüstem Duyuran, vice president of the Istanbul Archaeological Museums, in the site of the Palace of Justice construction. Mamboury regularly visits the excavations.

He writes that a team has been demolishing the walls of the old prison for eight days. Six steps on the street which intersects the German Fountain horizontally have been uncovered. Mamboury thinks that these steps are the basis for a floor covering. His later drawings demonstrate that these are the seats on top of a substructure with corridors which were found in the earlier excavations. Mamboury’s drawings of the Rüstem Duyuran excavations are so precise that it is still possible to create a three-dimensional imagination of the Hippodrome seats.

Following ten pages in his notebook are blank. Perhaps he intended to write something there at a later time.

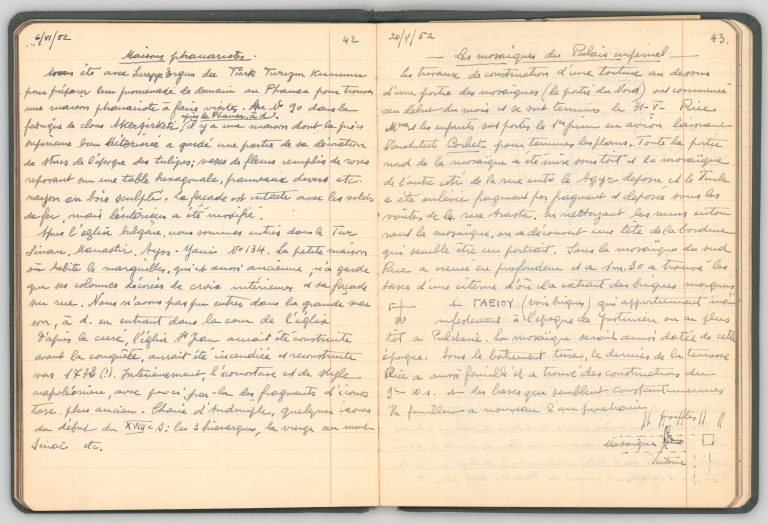

After a long time Mamboury visits Fener district for preparations of a sightseeing trip.

Fener Houses, 6 June 1952

Mamboury is also an author of scholarly tourist guides. His Istanbul Tourist Guide was first published in 1925. It is different than our modern tourist guides in a couple of respects: it includes drawings, plans, maps, photographs along with scholarly explanations and interpretations. It was published many times in French, English, German and Turkish. He also published an Ankara Tourist Guide in 1933. He worked very hard to prepare a general Turkey Tourist Guide until his death. His notes here are about his visit, along with Süreyya Ergün (director of tourism office), of a wooden house, Bulgarian church and the house of the church official. His notes end with an enigmatic count:

“Chain of Adrianople, a couple of icons of 18th century, three high priests, Virgin in the Mount Sinai etc.“

Mosaics of the Imperial Palace, 20 May 1952

The construction of the roof over the mosaics is finished. British archaeologist Talbot Rice has left Istanbul with his family. Corbet will draw the plans during the absence of Rice. Mamboury describes detailed finds of the excavations:

“While cleaning the walls surrounding the mosaic, a head, resembling a portrait was discovered. Rice excavated deep under the surface of the southern mosaic and found, 1,80 m deep, the basement of a cistern. There he extracted bricks, marked TAEIOY, which clearly belong to the time of Justinian or maybe to Pulcheria. The mosaic can also be dated to the same period. Rice also excavated under the Turkish building, behind the terrace and found structures from 9th-10th centuries, and bases from the time of Constantine. He will continue his excavations next year as well.”

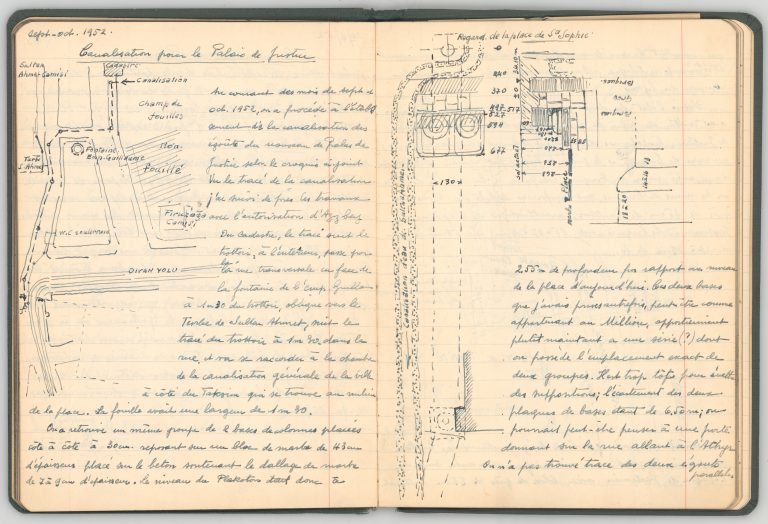

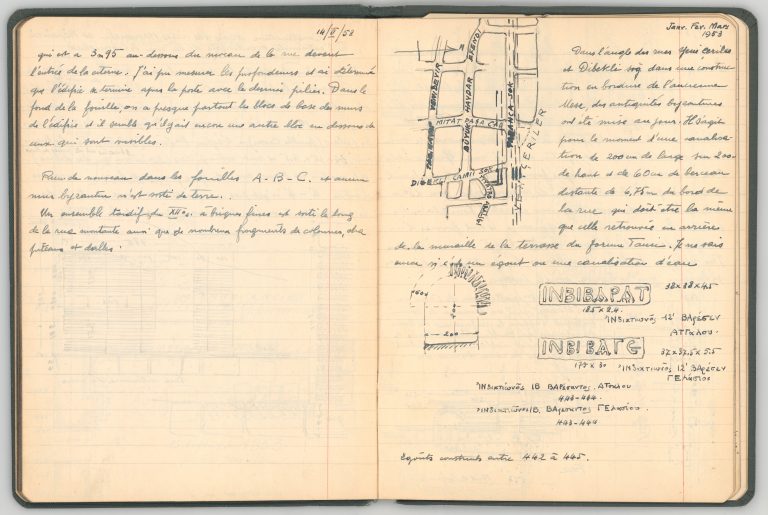

Canalization for the Palace of Justice, September-October 1952

Having heard about the canalization works for the Palace of Justice, Mamboury visits the site with the permission of Aziz Bey, and records what he observes. In these months the Hippodrome area practically resembles to a construction site. He follows nearly every building activity in the district. His mind is full of architectural plans and he tries to place new finds into these plans. These finds include walls, cistern and pools, column capitals, bricks, floor coverings, “Turkish walls” which are upheld by Byzantine bases.

“There was a Turkish neighbourhood which was destroyed in a fire in 1913. That’s why even the marble slabs of the Plakoton were even taken away. The streets have preserved the Byzantine ruins better than the houses.”

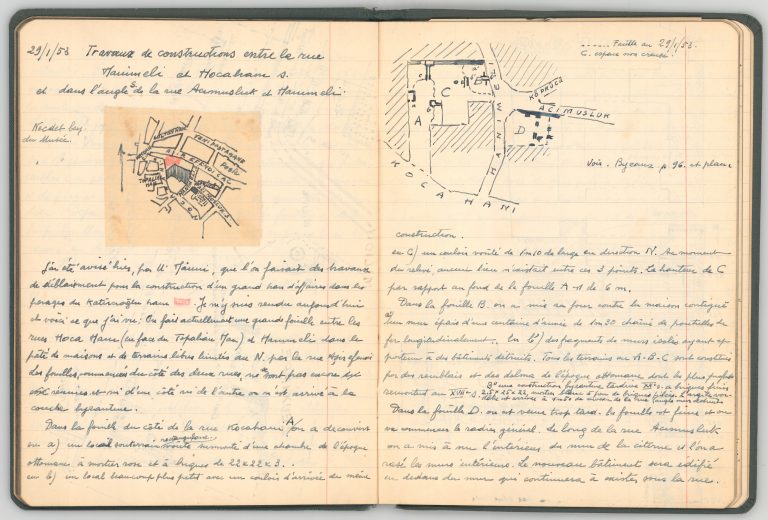

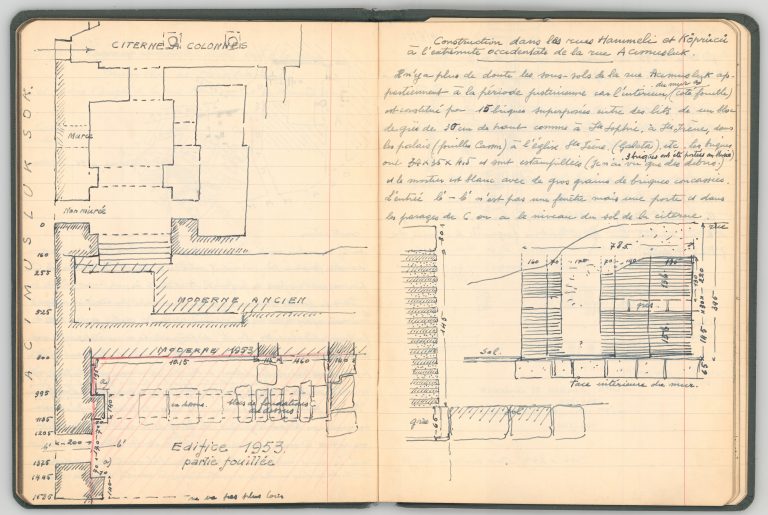

He was always in the area, his notebook in his hand, with the museum officials. Mr. Maumi tells Mamboury that new business blocks were constructed in the vicinity of the Katırcıoğlu Han. He rushes there with Necdet Bey from the museum.

Sometimes he was not able to make observations anymore:

“When we arrived there it was too late. The excavation is over and they are going to construct the foundation of the building. They razed the inner walls of the cistern along Acımusluk street. The new building will be built within the wall which will continue to exist under the street.”

Mamboury’s last entry is about the Çırpıcı Stream.

Çırpıcı Valley, 28 June 1953

“In search of the ruins of Theotokos Evergetis”

After the hectic works in and around Hippodrome his visit to the Çırpıcı Stream apparently softens his nerves and gives him pleasure. He records the orchards, vineyards, several places where he could find spring water, and graveyards:

“We gently leave the graveyard which has very picturesque corners.”

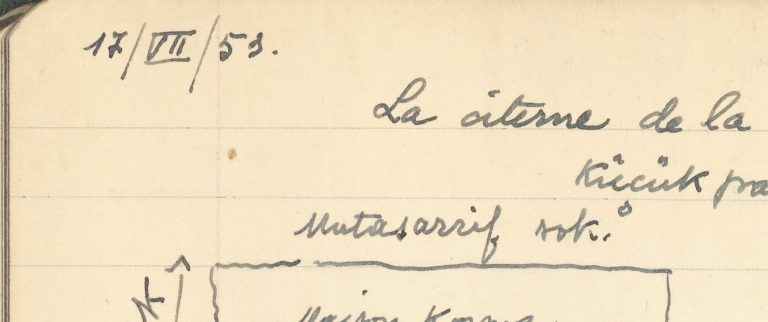

Finally he arrives at the çiftlik (farmstead) of Midhat Paşa. He carries the reference of the manager of the Istanbul Club, Mr. Achille Arvanitaki, so Mamboury is received by the housekeeper warmly. He wants to see the hagiasma-cistern inside the premises. He takes the measurements and makes drawings as usual. He appears to be certain that the cistern was once part of a monastery.

“Might this have been Theotokos Evergetis that once Janin mentioned? He places this monastery around the Çırpıcı Stream or Haznedar Stream, 2 miles (3.304 m) away. Nevertheless Silivri Kapı is 2.500 m away from the hagiasma, not 3.304 m away. At the other side of the Çırpıcı Stream there is another hagiasma which fits better to the description of the monastery. Which one might have belong to the monastery?”

He cannot think without measurements.

Mamboury within Müller-Wiener archive

Müller-Wiener refers to Mamboury‘s notebook as “Grünes Notizbuch“ (Green Notebook).

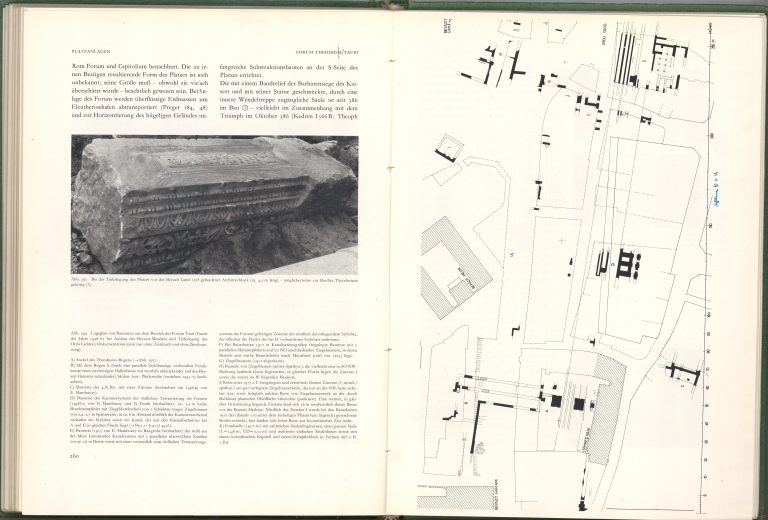

This drawing and Müller-Wiener‘s notes aside depend on Mamboury‘s notebook, page 33, dated 30 May 1950 where Mamboury made notes on the Capitol area.

Müller-Wiener’s handwriting on top left corner reads: “Byzantinische Gewölbebauten (nach Mamboury, Capitol)”

“…. im grünen Notizbuch E. Mamboury!“

At the top left corner Müller-Wiener‘s handwriting reads: „According to the notes of E. Mamboury“.

He is describing masonry like mortar, tiles, and small squared blocks. There is also a small corridor (couloir) with Topos-Inscriptions. The statements about the staircase or the building itself are unreadable. We couldn’t identify which building it might be.

Müller-Wiener draws a plan of certain Byzantine remains in Uzunçarşı Street, Istanbul. Mamboury had published his notes about the same remains. Unsatisfied of Mamboury‘s assessment, Müller-Wiener notes, on top right corner: “Location is not specified in Mamboury, Byzantion 11 (1936), p. 255. Are the ruins on Ismetiye Street??“

After the Notebook

Three years after his retirement (March 19, 1991), Müller-Wiener came to Istanbul for the last time with his book’s layout, Die Häfen von Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, which he brought in his suitcase to be published in Turkish. Sadly he died in the same year Istanbul.

Mamboury’s notebook and Müller-Wiener’s last book tell us that these two scholars were busy with Istanbul until the end of their lives. This small notebook which connects the archive of Mamboury to that of Müller-Wiener demonstrates that scholarly works stem from accumulation of knowledge and research. Besides, this notebook is also in the intersection of the works of Alfons Maria Schneider, Theodor Wiegand, Kurt Bittel, Jonathan Bardill, and Cyrill Mango.

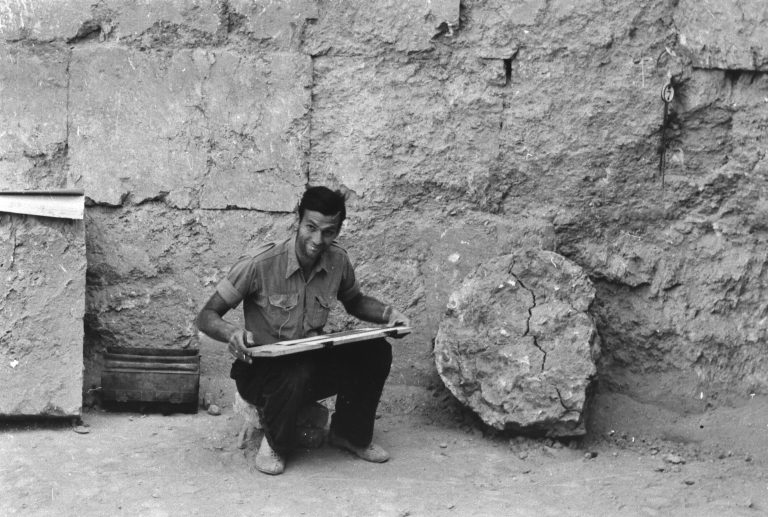

Mamboury‘s archive contains numerous drawings. What is noteworthy is that Mamboury always took measurements for his sketches. These drawings are sometimes our only source for archaeological remains and many of which have dissapeared. Mamboury participated in various archaeological works of Istanbul Archaeological Museums with the Turkish scholars, as well as with the teams consisted of German, British, and French scholars. This wide network might be a sign of his vast experience and ability to draw accurate sketches.

Müller-Wiener‘s great archive also includes diverse materials on specifically Istanbul; such as architectural drawings, topographical information, articles, travellers‘ accounts, drafts of his conference papers, and photographs. Yet one striking feature of his archive is that his opinion was consulted in relation with city planning of Istanbul by the authorities.

Report of the German Archaeological Institute, Istanbul Branch Vierteljahres und Jahresberichte der Abteilung Istanbul includes a report of the field trip of Mamboury and Aziz Ogan to Küçük Çekmece in 1939.

This demonstrates the cosmopolitan nature of Istanbul as well as cooperation of scholars of various nationalities who worked together. Mamboury became an influencial person in this cosmopolitan world with his skills.

The hands of these two researchers, who have made unique contributions to the history of Istanbul, have touched this notebook. These two people focused on Istanbul’s disappearing heritage; it is very likely that they strolled through the same streets and they both wrote and nourished their stamina for the same objective: I must document before the remains disappear and keep them in an archive!

Curators

Alkiviadis-Alexandros Ginalis

Berna Güler

Murat Köroğlu

Text

Berna Güler

Editorial Work

Ulrich Mania

Exhibiton Technical Works

Engin Dikkulak

Mareke-Johanne Ubben

We thank to

Ali Akkaya

Beyoğlu Galatasaray Müzesi

Galatasaray Lisesi

Duygu Erözbek

Emir Alışık

İstanbul Araştırmaları Enstitüsü

Jesko Fildhuth

Nathalie Defne Gier

Zeynep Kuban

![2- D-DAI-IST-R15409 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/2-D-DAI-IST-R15409-scaled-ptk2i9j8osaz9ty2enlwdng8l3u1e8tucbm4dncumy.jpg)

![3- DAI_IST_Archiv_NL_Mamboury_0073_13 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/3-DAI_IST_Archiv_NL_Mamboury_0073_13-scaled-e1661026028235-ptk2xhj1pmx8u43lgpc8yl1zg9g26gefsee3yvcow0.jpg)

![4- D-DAI-IST-1020 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/4-D-DAI-IST-1020-scaled-ptk348zdr569ywtw3zwha2qpf18it9cdbg0al2plm6.jpg)

![5- Kartvizit [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/5-Kartvizit-ptlrhuvqyzgcqeczue1cqjnuf5k5txnks44y4fty26.jpg)

![6- defterin ilk sayfasi [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/6-defterin-ilk-sayfasi-scaled-ptlro0pnrvw0uderv1xb2zomm36sai48am3jdqp1ms.jpg)

![21- 16 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/21-16-scaled-ptltqwim5gmx5sgvojahtk0xnuqx94nrtf0ox8aakg.jpg)

![23- D-DAI-IST-10081c [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/23-D-DAI-IST-10081c-scaled-ptltx0gukp00mjle06d710iso0mtaawynnob7z864g.jpg)

![25- D-DAI-IST-KB01519 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/25-D-DAI-IST-KB01519-scaled-ptlu22tq3r31dttbdo705re2vtwaptdsfpvl7z2kkk.jpg)

![30- D-DAI-IST-R28872 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/30-D-DAI-IST-R28872-scaled-ptluiqikiuqz9q6f6thimi9b6ah52ljgsmarx9l340.jpg)

![35- D-DAI-IST-R6127 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/35-D-DAI-IST-R6127-scaled-ptluw0yf5ix2qcv12y9xkzrwynanzpc2e6465o39q8.jpg)

![36- D-DAI-IST-R6146 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/36-D-DAI-IST-R6146-scaled-ptluxyih79kali1zsscbpi80x5rttb07bqe3o584xs.jpg)

![41- D-DAI-IST-R30453 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/41-D-DAI-IST-R30453-scaled-ptlv95r8n6vg9brtw0ml4ipr6ovzmmi9yy0niettds.jpg)

![55- DAI_IST_Archiv_NL_Mamboury_0722v_Merged [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/55-DAI_IST_Archiv_NL_Mamboury_0722v_Merged-scaled-ptmdy4bmij4oxxhw2xdp7m0irfz5af5vac0e1lgr74.jpg)

![57- D-DAI-IST-R9395 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/57-D-DAI-IST-R9395-scaled-ptme2qox8sg3yiw0mhack52retmilrfq25c2n2p4ao.jpg)

![69- DAI_IST_Archiv_NL_Mamboury_0498_3 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/69-DAI_IST_Archiv_NL_Mamboury_0498_3-scaled-ptmeoa5rv3xo0tlluahk77e1hpgc01ya0rjnkcrbpc.jpg)

![71- Drawing_Mamboury_Box_45_Ist.Einzelbauten_29 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/71-Drawing_Mamboury_Box_45_Ist.Einzelbauten_29-scaled-ptmew61172pz6rh4mnununu8p5d2xp9mh1tdhfsydc.jpg)

![72-Drawing_Mamboury_Box_45_Ist-Einzelbauten_29 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/72-Drawing_Mamboury_Box_45_Ist-Einzelbauten_29-scaled-ptmexiwn2gkvyhi4p8z9gbi7l6o61ynnzrqmftshds.jpg)

![74- Capitol [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/74-Capitol-scaled-ptmf007b3pzp218pjw9a2at0emw8n3hclj7l22n18g.jpg)

![77- 53 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/77-53-scaled-ptmf4hvjr850iypvbu53z60akwrdf1b6jrf3lnzbi8.jpg)

![78- 54-MüWi_Box26_F6_2 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/78-54-MuWi_Box26_F6_2-scaled-ptmf5qzsv9us08wc0dn7aumf3ekzoiaapyqemy4f7k.jpg)

![79- 55-MüWi_Box26_F6_4 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/79-55-MuWi_Box26_F6_4-scaled-ptmf6otzpb53m7j6is9rsm30h9y7dm0mum7vwwq8zk.jpg)

![80- 58 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/80-58-scaled-ptmf7qfjaokkim0kf8iukclg8osvxi5wbsbb3z6i2o.jpg)

![82-Box12_item103_Mamboury [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/82-Box12_item103_Mamboury-scaled-ptmfa3yukltnv4kbjrhwd90ear3adylgzjohs5nocg.jpg)

![83- gazete_eki_ilk_sayfa [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/83-gazete_eki_ilk_sayfa-scaled-ptmfbmhhkzwakid4pf29dv94r3mkselwj1inm7eubk.jpg)

![84- Mamboury_1 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/84-Mamboury_1-scaled-ptmfcss84ji72ynoufch02kvhfu3es9touvi7no4jk.jpg)

![85- Mamboury_2 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/85-Mamboury_2-scaled-ptmfdz2yo343ley8zfmom9wm7s1m15xquo8ct3xerk.jpg)

![87- 64 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/87-64-scaled-ptmfi2nmh2q486zw1pf3zqnzh9u8ln7lqynl5julmo.jpg)

![88- DAI-IST A VII-2 (18) [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/88-DAI-IST-A-VII-2-18-scaled-ptmflfwsypc3tw3rdntzfe2g3z8l6lkz7mt828utc0.jpg)

![Screenshot_2 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/Screenshot_2-ptmfmzda5xfgeaix1r4ihe8mrv71iupyhrt1cm1mv4.png)

![Screenshot_3 [Attribution: unknown; Copyright: not defined]](https://www.dainst.blog/daistanbul_blog/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/elementor/thumbs/Screenshot_3-ptmfnporhafhfdgos2i2f7ljenlbidmfxe2mscym0w.png)