Eva-Maria Czakó (19.12.1918–16.6.2012) was the first and remains the only female photographer at the DAI Athens. When the Institute was reopened after the Second World War, she worked as a professional photographer from 1954 to 1962, capturing in her photos Greek antiquities and, of course, the Institute’s excavations and finds.

Youth and early career

After studying art history, Czakó trained to become a professional photographer at the renowned Bildarchiv Foto Marburg (German Documentation Centre for Art History). Drawing on her expertise, she worked at the Marburg Central Art Collecting Point under the direction of Richard Hamann in post-war Germany. This ›collecting point‹, the first one established by the American military government in the occupied zone, systematically documented paintings that had been plundered as war booty or stored in collections in order to facilitate their return to their places of origin. From autumn 1945 to 1949, Czakó and a colleague documented and photographed 200,000 paintings in the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point. With her extensive experience in photographing art objects, she was ideally suited for the task awaiting her in Greece.

1954–1962 at the DAI Athens

In the days before job openings at the Institute were publicly advertised, the directors turned to acquaintances or educational institutions in search of qualified restorers or photographers. We thus do not have precise information as to how Czakó’s connection with the DAI Athens came about. Her prior acquaintanceship with Dieter Ohly (as Erika Kunze-Götte recalls) or with Hamann might have played a part in it. Hamann not only had conducted a large-scale project for the photographic documentation of Greek monuments in the 1920s, but in 1924 he also co-authored ›Die Skulpturen des Zeustempels zu Olympia‹ (›The Sculptures of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia‹) with Ernst Buschor, the then-director of the DAI Athens (Buschor – Hamann, 1924). Since Czakó and Ohly published a small volume on ancient gems for Buschor’s 70th birthday, some combination of these connections might have been decisive.

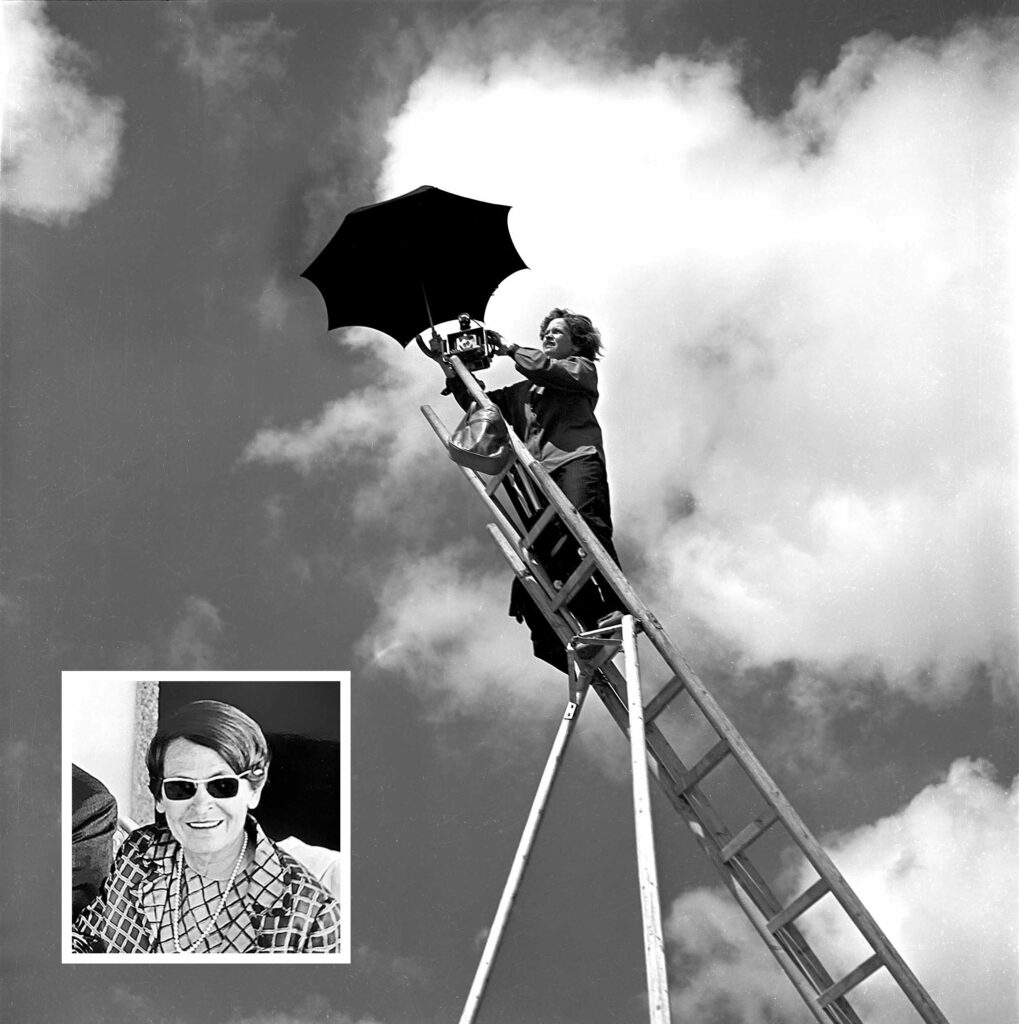

As the DAI Athens slowly resumed its regular operations and excavations at the traditional research sites of Olympia, the Kerameikos, and the Heraion of Samos in 1954, Emil Kunze was able to recruit »Fräulein Czakó« (fig. 1) for the department.

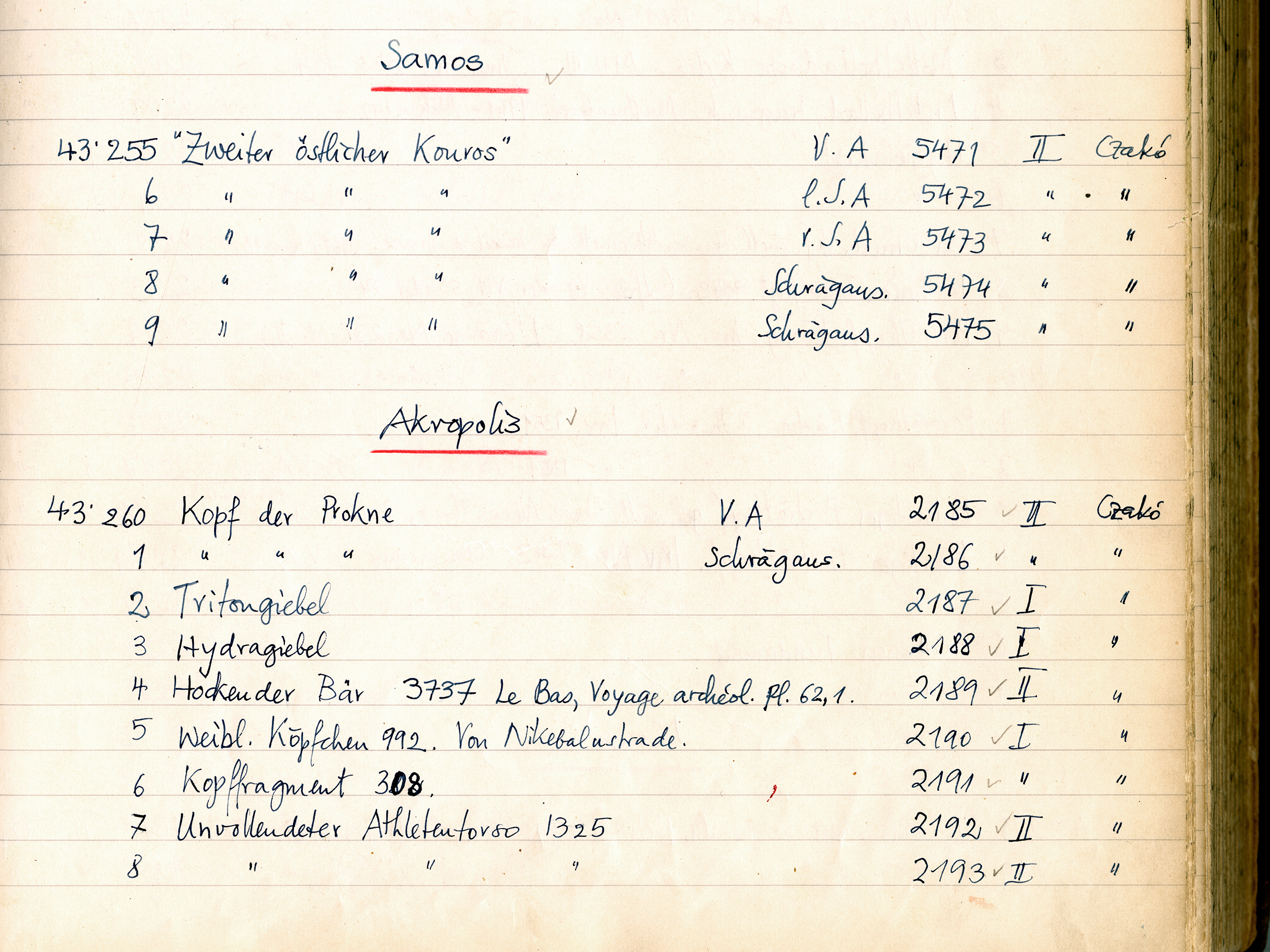

Czakó was appointed to the newly created position of photographer on 1.10.1954. A ›photo lab‹ was immediately set up in the basement of the Institute, which subsequently became her responsibility. Archival correspondence bears witness to the tedious process of importing new equipment from Germany to Athens. Czakó also was in charge of maintaining the Institute’s huge photographic archive, which already contained over 30,000 negatives, most of which were glass plates. During her tenure as the Institute’s photographer, the holdings of the photo archive increased by over 6,500 photographs. All of these photographs are accessible online via iDAI.objects. Czakó’s personal authorship of photographs was recorded in the Institute’s holdings (fig. 2) and indicated by a stamp on the back of each photo print.

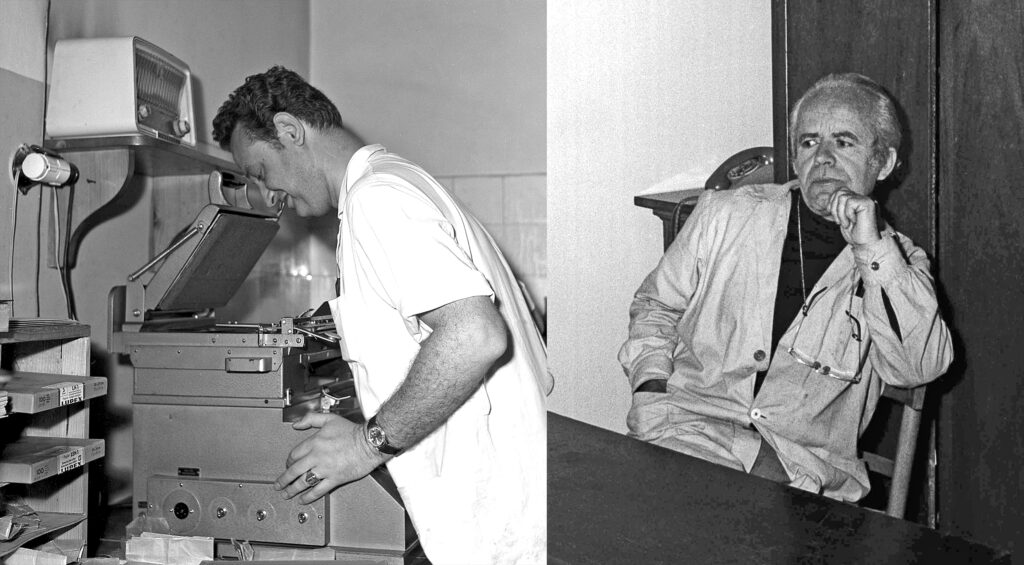

Czakó had assistance at hand right from the start. Twenty-year-old Eleftherios Feiler, the son of the Institute’s porter, who had grown up in the family’s apartment in the DAI, assisted Czakó for several hours now and then. As demand for new photographs and prints steadily grew, first he, in 1956 (shown below in a photograph taken by Czakó), and later another local employee, Anastasios (Tassos) Tsimas (fig. 3a. b.), were hired. Czakó in fact trained both men as photo lab assistants and photographers. Although they initially were commissioned to produce high-quality prints, they later also took photographs themselves to meet the ever-growing demand.

Czako’s talent was obvious and first became more widely known in archaeological circles through the photographs that she contributed to Dieter Ohly’s aforementioned ›Griechische Gemmen‹ (at the time, Ohly was Second Director of the Institute). Vierneisel (1994, 7) aptly described her work as follows: »While it was still common at that time to illustrate cut stones almost exclusively with their positive, dull plaster cast, she succeeded wonderfully in capturing the fleeting image in a sparkling gem in photographs«.

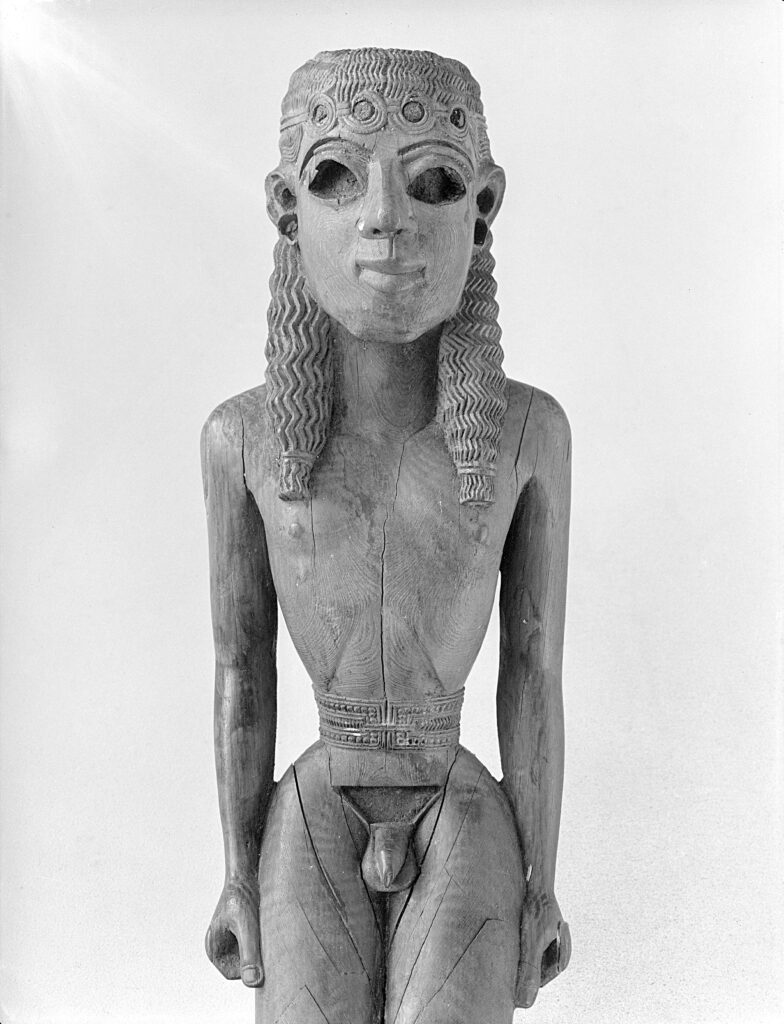

Since the 1950s, the task of archaeological photographers has been to reproduce objects without injecting any interpretation. Czakó had a special gift for reproducing objects with particularly great vividness. Gerhild Hübner (private communication with K. Sporn, January 2023) describes this gift as a special »receptivity to form«, i.e., »the talent to see and the ability to capture the peculiarity of the object«. Czako’s sharp eyes also enabled her to make her own observations on the coherence of scattered fragments of a statue. On her own testimony, she recognized that a kouros head exhibited in the Istanbul Museum fit fragments of a kouros in the Museum of Samos. Her conjecture was confirmed by Walter-Herwig Schuchhardt (Vierneisel 1994, 7. 34 and personal information of Gerhild Hübner to Katja Sporn; cf. also Eckstein 1962, 47. 57).

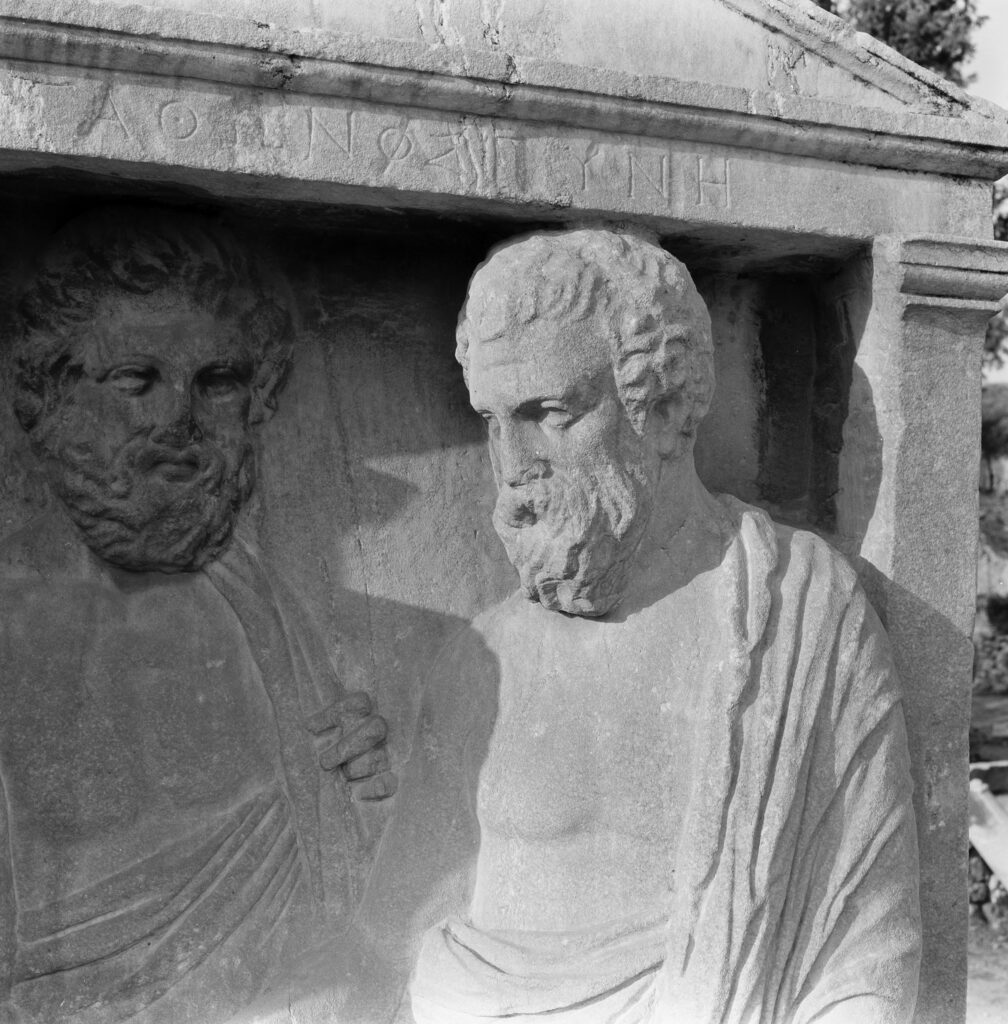

Czakó quickly specialized in ancient sculpture. »Her aspiration was to document works of art appropriately and give them the respect they deserved«, as the archaeologist Klaus Vierneisel explained in the introduction to the catalogue of her 1994 exhibition »Blick auf Griechenland. Fotografien 1954–1963« (Czakó-Stresow 1994, 7). He further wrote: »For sculpture at that time, this meant capturing the organic-plastic development of sculpture, with all its transitions and modulations, in a photograph, without any effects and ideally also while avoiding artificial lighting. This work ethic, of course, presumes artistic intuition, but also scholarly discussion with the archaeologist, if the resulting image was to achieve a high degree of authenticity.« Her method enabled her to bring even badly damaged sculptures vividly to life in photographs, making her arguably the best archaeological photographer of sculpture of her time.

The subjects of Czakó’s photographs ranged from the figures of the Parthenon sculptures (fig. 4) on the Athenian Acropolis and finds from the workshop of Pheidias in Olympia to ancient gems (Ohly [1957]) and Corinthian helmets, providing illustrations for

the works of many important Classical archaeologists (e.g. Brommer 1967). Sometimes she was credited for her work, and sometimes, as was still customary at the time, she went unmentioned.

»Czakolein« (by Maria Tzannetakis) or »Czakoline,« (by Alfred Mallwitz et al.) as she was called by colleagues and friends, was well-liked by her colleagues and well-integrated into the excavation teams during campaigns. This is attested by photos of excursions taken by the scientific staff and local excavation workers and their families (fig. 5).

During the campaigns at Olympia, she made use of the darkroom (Dunkelkammer) there and developed the images she had taken daily. As Erika Kunze-Götte recalled in an interview with K. Sporn in 2021, during the campaigns 1959–1960 in Olympia, when Emil Kunze sometimes fell into a long monologue after dinner with the excavation team, Ms. Czakó was able to divert his interest with the sentence »the photo prints should be ready by now« and bring the evening to a timely close.

Since better-paying positions in German museums threatened to lure Czakó away, the Athens department negotiated with the DAI headquarters in Berlin at least twice over the years to secure her a higher salary in light of her exceptional expertise. In total, Czakó remained in Greece for almost nine years. She resigned from her post at last on 31 December 1962 and returned to Germany.

Return to Germany

In 1963 Czakó’s personal circumstances changed: she married the publisher Gustav Stresow, director of the famous Prestel publishing house, specializing in the arts, architecture, and photography. She changed her surname to Czakó-Stresow (fig. 6).

She remained in contact with her former colleagues, spending holidays with them in Greece, and remained involved in archaeology. In 1975, her husband edited the volume ›C. Hofkes-Brukker, Der Bassai-Fries – in der ursprünglich geplanten Anordnung‹, for which Eva-Maria Stresow-Czakó made new photographs. Hofkes-Brukker (1975, 6) stated: »In her photographs, Mrs. Stresow knew how to emphasize the conceptual unity of friezes and to keep high relief sculpture legible everywhere, even in shaded areas, while foregoing impressive lighting.«

A cross-section of her work was the subject of the aforementioned exhibition »Eva Maria Czakó-Stresow ›Blick auf Griechenland: Fotografien 1954–1963‹«, which was organized and edited in Munich in 1994 by the archaeologist and former colleague of Czakó’s, Klaus Vierneisel.

Bequest at the DAI Athens

Thanks to the generous donation of her nephew Ulrich Nolte (son of Mr. Stresow’s sister), we gratefully received more than 800 of Eva-Maria Czakó-Stresow’s private photographs in 2019. These photographs, taken during the years that Czakó lived in Greece, capture the landscapes, nature, and people of Greece, documenting this bygone era. These photographs – her legacy – will also be accessible via iDAI.objects in the near future.

For now, the following selection of images from our photo archive and from her bequest (fig. 7–13), some of which derive from research sites of the DAI Athens and others from Czakó’s travels, give insight into the impressive range and artistic skill of her oeuvre.

Excavation sites of the DAI Athens

Kerameikos

Olympia

Samos

Rural Greece 1950s–1960s

Works cited and further reading:

Brommer 1967

F. Brommer, Die Metopen des Parthenon. Katalog und Untersuchung (Mainz 1967)

Buschor – Hamann 1924

E. Buschor – R. Hamann, Die Skulpturen des Zeustempels zu Olympia (Marburg 1924)

Czakó-Stresow 1994

E.-M. Czakó-Stresow, Blick auf Griechenland: Fotografien 1954 –1963 (München 1994)

Hofkes-Brukker 1975

C. Hofkes-Brukker, Der Bassai–Fries: in der ursprünglich geplanten Anordnung (München 1975)

Ohly 1975

D. Ohly, Griechische Gemmen: Aufgenommen von Eva Maria Czakó (Wiesbaden 1975).