What happens to newly exposed remains after an archaeological excavation is finished? What would it stand for and mean for the public? Is it actually worth preserving and presenting it?

What does a conservation architect do at an archaeological excavation? In this contribution, let us explain very briefly what a conservation architect does on a dig and some common terms about protective measures in archaeology.

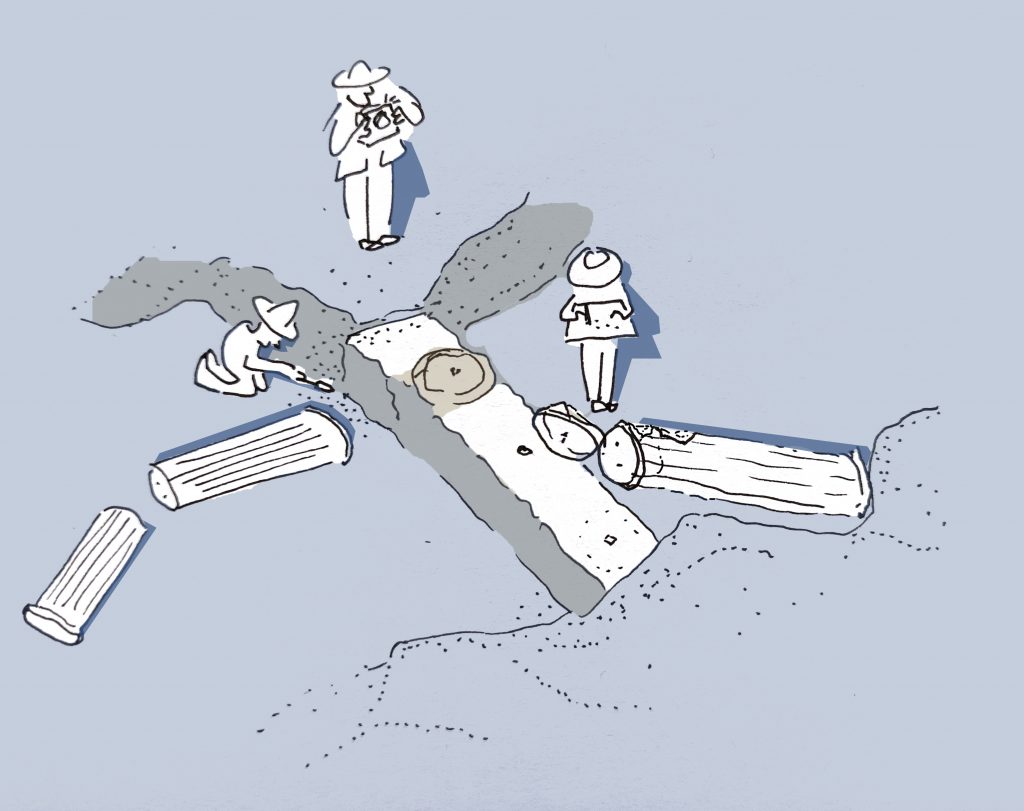

Architects have taken part in archaeological fieldwork since the earliest excavations. Archaeologists investigate traces of past cultures under soil, including different types of artefacts as well as architectural remains, in order to gain information to understand the history of a site. The architect’s duty, however, is to trace, to document, and to interpret the still standing, but also newly revealed architectural remains within their contexts, and if required to establish a concept for preserving those remains. Therefore architectural conservation has long been counted within the program of archaeological works. The need of protecting remains from the past derives from the destructive nature of archaeological excavation methods and praxis.

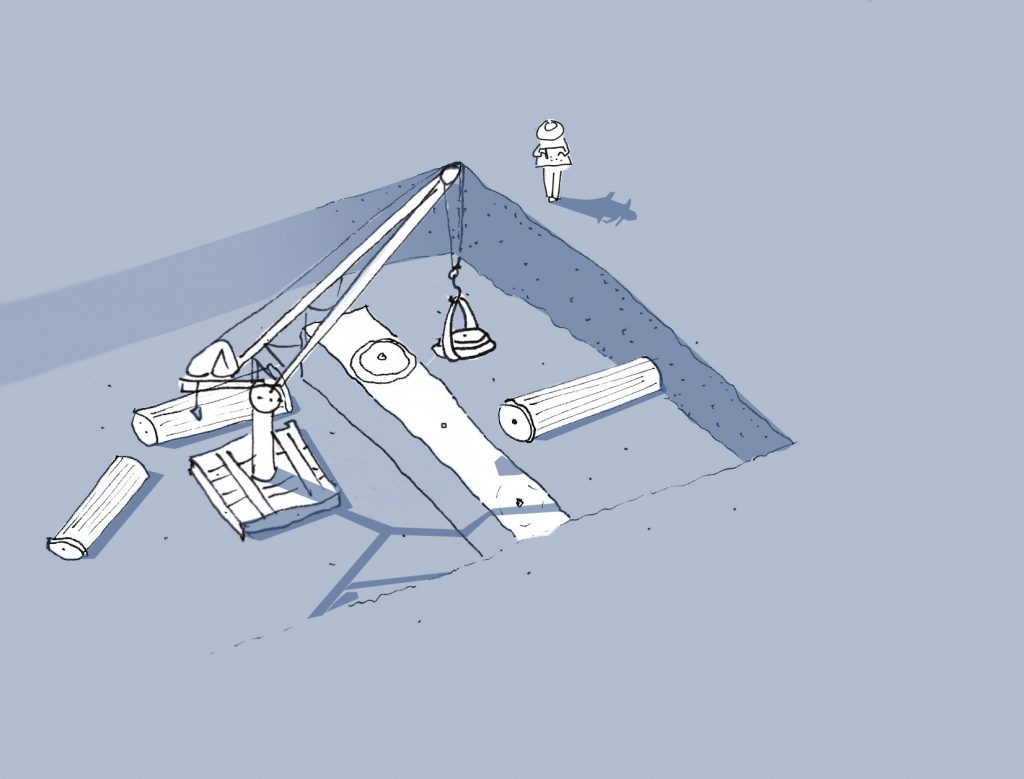

An architectural structure is usually found not in its best condition. In general, ruins, lacking structural integrity, is the matter. If a building has outstanding features -regardless whether it will eventually be presented to the public, or not-, it should be protected and consolidated. In order to preserve them in their discovered state, conservation measures come into play. Main aim of this initial hands-on intervention is to stabilize the state of the finding, by strengthening its resistance against uncertain conditions (e.g. weathering, visitors, humidity etc.).

However, in some cases, for the sake of extending life time of the revealed finding, more comprehensive actions might be required, i.e. restoration, which is more comparable with a surgery than medication. Actions within this approach may vary from replacing damaged parts to removing previous conservation implementations. Restoration is mostly concerned with the overall appearance of the monument.

After all, as determined by international charters and guidelines, both techniques serve the preservation of the historic fabric of the finding.

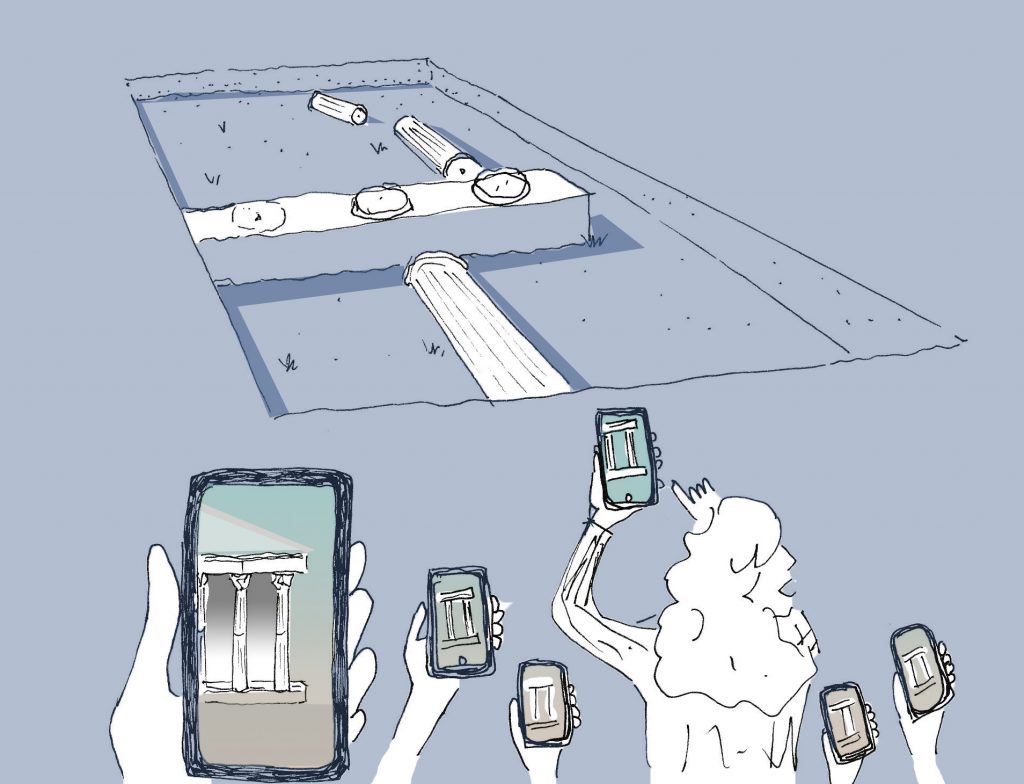

Visiting an archaeological site can sometimes be a quite discouraging and disappointing experience for the visitor, as the sites are often hard to understand at first glance. What does a visitor really expect to experience on a site? A remote archaeological site within the woods with no proper path can sometimes be way more charming than a site with thousands of visitors a day, because it still offers the feeling of discovering a place. So, what would you, as a visitor, really like to see at a site?

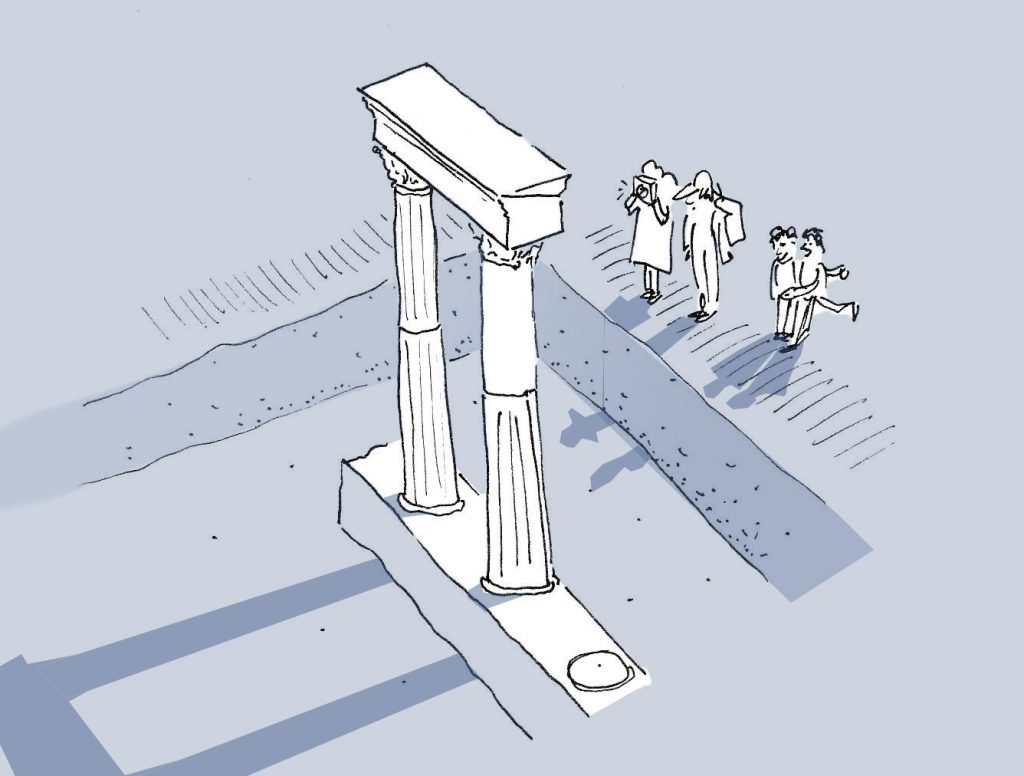

For places, that written information or visualisations are not enough for visitors to imagine the site, reconstruction is another method to visualise the past. In a tangible reconstruction project, modern techniques and materials may be used moderately, as long as the added parts and elements are distinguishable from the original fabric. However, the concept of “reconstruction” is way beyond the concept of “preservation”, e.g. it might interfere with the surviving evidences or falsify its original characteristics. Therefore, the implementation of on-site reconstructions needs to be very carefully considered before being applied. Preferable reconstructions are only provided as graphics or models.

A special concept of reconstruction is anastylosis. Anastylosis could be described as reverse engineering. The general idea is to reproduce a destructed building with its original building materials and techniques. To be able to execute such a project, a thorough documentation of all building stones and their re-contextualisation are required. Only based on a detailed building archaeological study (Bauforschung) should an anastylosis be considered. Anyhow, in several cases the original material may not have the required physical properties anymore that it would need to fulfil its structural function. As a result, the planned anastylosis can easily turn into a reconstruction.

In recent decades digital tools have started to diffuse into the field of archaeology for various purposes. This digital applications does not only help specialists to conduct their research, but also create a virtual platform for the visualisation and presentation of archaeological remains (augmented reality and virtual reality), which eventually enables visitors to experience the site virtually. Here, possible reconstructions as well as finds in their original context can be experienced as augmented reality on site. Digital tools may be a chance for the future to preserve the actual remains and presenting the archaeological results in an adequate but easy accessible digital format.

Architects, heritage conservators and restorers provide the necessary documentation of the state of conservation, damage mapping, and analyses to develop tailor-made concepts for the protection, preservation, conservation, consolidation, and presentation of archaeological remains, which then are carried out under their supervision.

Seçil Tezer Altay

German Archaeological Institute, Istanbul Department

Further reading

Martin Bachmann, Çiğdem Maner, Seçil Tezer, and Duygu Göçmen (eds.) Heritage in Context, MIRAS 2, Istanbul: Ege Yayınları, 2014.

DAI, (ed)., Bewahrung archäologischen Kulturguts für die Nachwelt – Restaurierungs- und Rekonstruktionsprojekte des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, DAI Architekturreferat des DAI, Zentrale. Berlin: DAI, 2011.

English Heritage (ed.) Practical Building Conservation. Conservation basics. Farnham: Ashgate, 2013

Petzet (2004), Principles of Preservation:

https://www.icomos.org/venicecharter2004/petzet.pdf

Katja Piesker, Burcu Akan, Duygu Göçmen, and Seçil Tezer Altay (eds.) Heritage in Context 2, MIRAS 4, Istanbul: Ege Yayınları, 2018.