The ‘Gurnellia’ is situated on the southwestern foothills of the city hill of ancient Pergamon, above the Selinus River and its recently investigated embankments (2023). Today, the substructures facing both sides of the valley create a rectangular terrace on the slope, known as the ‘Büyük Alanı’ or ‘İttihati Terakki Parkı’ (Fig. 1). The name Gurnellia probably dates back to the time of the Greek Quarter in Bergama, which began to develop in the late in the 19th century. It is most certainly deriving from the word γουρούνι for pig – and could refer to its use as a pig market. This is reflected in the Turkish name ‚Domuz Alanı’.

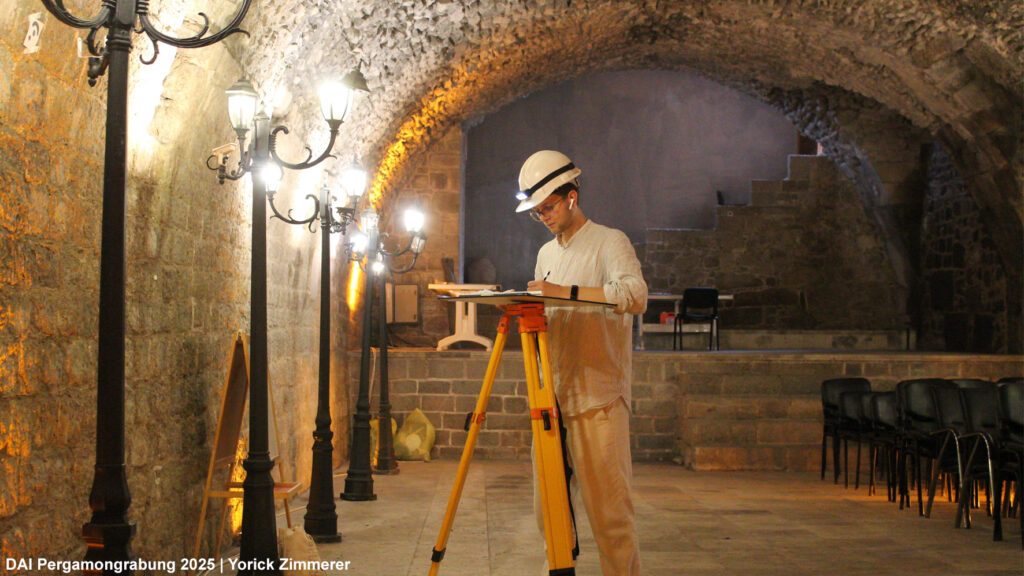

The substructures of the ‘Gurnellia’ consist of elongated chambers, some of which are partially preserved with remnants of their vaults. According to Corinna Brückener (Brückener 2018, 9), they measure approximately 63 x 140 m and follow a roughly north-south orientation (see the Archaeological Map of Pergamon). The southern vault – located below the Akropol Restaurant – survives only in western fragments, while an additional vault defines the western edge of the terrace. This latter structure was further excavated by the Bergama Museum in 2025 (Fig. 2).

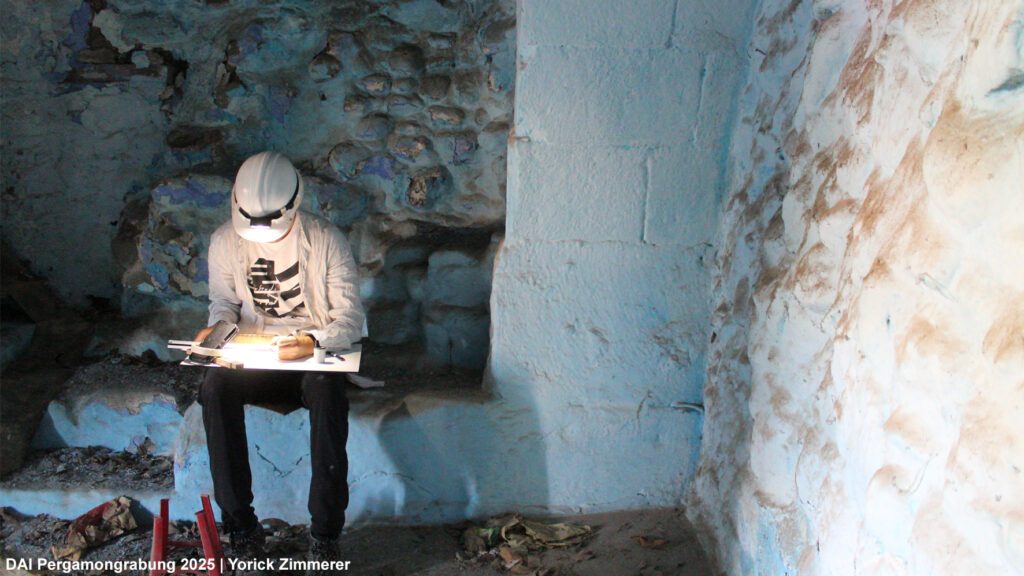

During the 2025 summer season, the remains of the ‘Gurnellia’ were reexamined for the author’s master’s thesis at the Department of Historical Building Research and Monument Preservation at the Technical University of Berlin, and as part of the TransPergMicro project (Fig. 3). The building documentation recorded both long-studied features and structures that were newly discovered or had been forgotten. Elevation and section drawings at a scale of 1:50 were produced on the basis of tachymetric measurement and supported by orthomosaics created using the ‘structure from motion’ method.

The ‘Gurnellia’ was first described in the Athener Mitteilungen in connection with the Pergamon excavations of 1886–1898 as a large complex of ruins belonging to a Roman building (Conze – Schuchhardt 1899, 121). It was mentioned several times by Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Alexander Conze, and Paul Schazmann. Dörpfeld also refers to “monumental staircases, magazines, and other components” (Dörpfeld 1910, 387), which may correspond to Schazmann’s plans.

In addition, the ‘Gurnellia’ appears in several maps and plans, including the map of Pergamon published by Otto Berlet in 1913. This map is based on an undated architectural survey drawing discovered in the Zentralarchiv der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin. There are also several related drawings, presumably made by Schazmann in 1908 (Wulf-Rheidt 1994, 143, Fig. 1), although they lack an overall plan. These sections and views, titled Gurnellia, initially posed many questions, as they could not, with one exception, be associated with the known remains. However, by examining the surrounding area and comparing the drawings with the results of the recent building documentation, the understanding of the structure gradually became clearer.

In the recent research, Wolfgang Radt and Günther Garbrecht discussed a later reuse of the vaults as cisterns (Radt 1999, 158), while Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt examined their urban context and Corinna Brückener compared the construction techniques of the substruction vaults with those of the Red Hall.

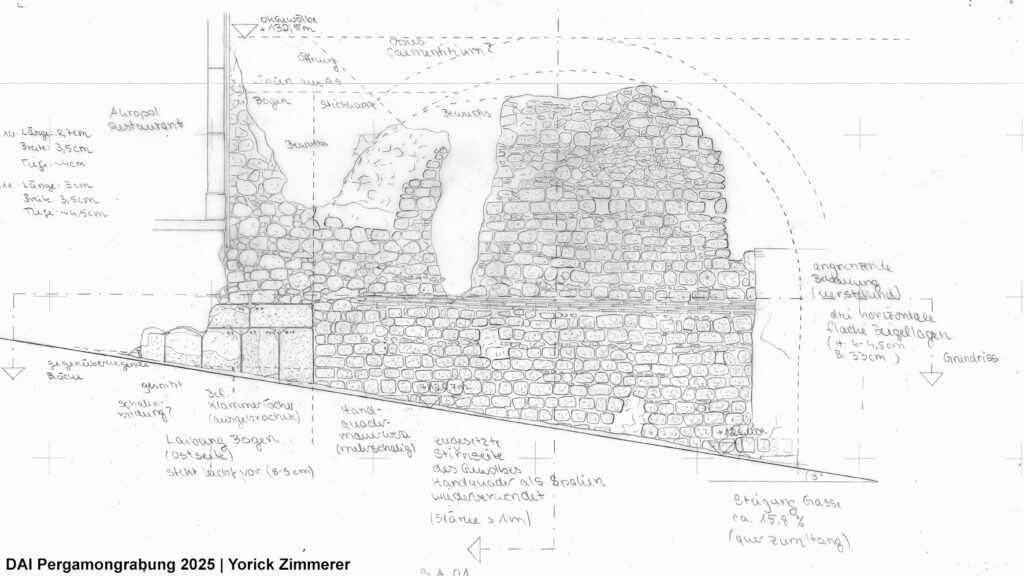

The vault walls are built of pointed andesite blocks that form a shell around an opus caementitium core. Above the impost layer, up to seven additional courses of blocks appear at the springing of the vault. Beyond this point, the barrel vault continues with radially set quarry stones, backfilled with opus caementitium. In the walls and at the apex of the vault, several arches, openings, and beam holes – some open, others filled – are visible. Comparison with other Pergamene structures featuring vaulted substructions, such as the Red Hall, the cryptoporticus of the Asklepieion, the Odeion of the Palaestra in the Gymnaisum, and the Amphitheatre shows that this construction technique was typical for Roman Imperial substructures in Pergamon.

During the examination of the surroundings, several arches and additional remains of the western vault were rediscovered. The arches west of the terrace (Fig. 4) correspond in both dimensions and position to those depicted in Schazmann’s plan, supporting the reconstruction of a monumental staircase. Near the presumed junction of the two vaults at the south-westernmost point, another arch aligned with the eastern wall of the western vault was identified (Fig. 5). An additional passage providing access to the terrace, located beside Koca Alan Sokağı and corresponding to the opposing arches of the southern vault, is also indicated.

The use of the southern vault as a cistern is confirmed by two 1.7 m thick front walls that divide the vault into several compartments, the presence of hydraulic mortar, and a Viertelstab, a typical cistern element (Garbrecht 2001). Along Koca Alan Sokağı, one of the orthogonal closing walls of the cistern can be observed next to the abutment of an arch constructed from precisely set andesite blocks (Fig. 6).

Given the dispersed nature of the remains of the ‘Gurnellia’, the documentation work focused on producing coherent plans of the entire structure to provide an overview of the related architectural elements. These plans form the basis for mapping construction phases and reconstructing the architecture.

In conclusion, the architectural remains clearly date to the Roman Imperial period, and any earlier Hellenistic structures can only be hypothesized. Nonetheless, the location of the ‘Gurnellia’ at the foot of the city hill, together with its orientation and its proximity to the buildings of the lower city, suggests that it may have served as an important point of connection. The results of the building documentation point to a sophisticated, accessible substructure linking different levels and spaces. The work undertaken in the 2025 summer season clarified the relationships among the various components of the ‘Gurnellia’ and unified them in measured drawings and a photographic record. This small-scale overview, absent from Paul Schazmann’s earlier plans, is essential for further research. Schazmann’s drawings, which depict far more than survives today, can now largely be associated with the investigated areas and thus support ongoing attempts to reconstruct the substruction vaults and the presumed architecture framing the terrace.

References

Conze – Schuchhardt 1899

Conze – C. Schuchhardt, Die Arbeiten zu Pergamon 1886 – 1898, Athener Mitteilungen 24, (Athen 1899), 97-240

Dörpfeld 1910

Dörpfeld, Die Arbeiten zu Pergamon 1908-1909, Athener Mitteilungen 35 (Athen 1910) 345-526

Wulf-Rheidt 1994

Wulf-Rheidt, Der Stadtplan von Pergamon. Zu Entwicklung und Stadtstruktur von der Neugründung unter Philetairos bis in spätantike Zeit, IstMitt 44 (Tübingen 1994) 135-175

Radt 1999

Radt, Pergamon: Geschichte und Bauten einer antiken Metropole (Darmstadt 1999)

Garbrecht 2001

Garbrecht, Stadt und Landschaft. Die Wasserversorgung von Pergamon, Altertümer von Pergamon 1, 4 (Berlin 2001)

Brückener 2018

Brückener, Die Rote Halle in Pergamon – Baugeschichte und urbaner Kontext (Brandenburgische Technische Universität Cottbus-Senftenberg 2018)