Dating sites and finds is the backbone of archaeology. Regarding Göbekli Tepe, we get lots and lots of questions about its chronology. These questions are absolutely legitimate (as actually really most of them are), and even more so with a site that claims to be the ‘first’ or ‘oldest’ (yet known) in many respects, the accuracy of dating becomes paramount. Of course we have a larger number of scientific publications on the topic, and more are under way as we type this. Yet academic publication sometimes needs its time and not everyone has access to a well-sorted research library. So, here we would like to provide a short summary of the story of Göbekli Tepe’s chronology.

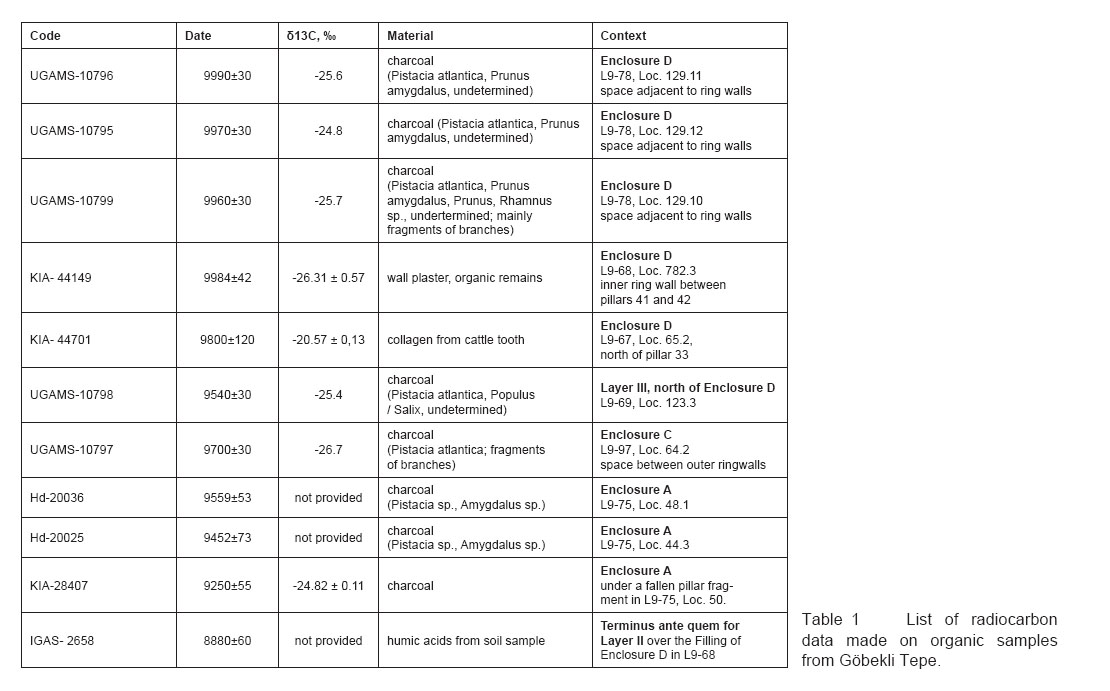

Table 1: List of radiocarbon data made on organic samples from Göbekli Tepe (DAI).

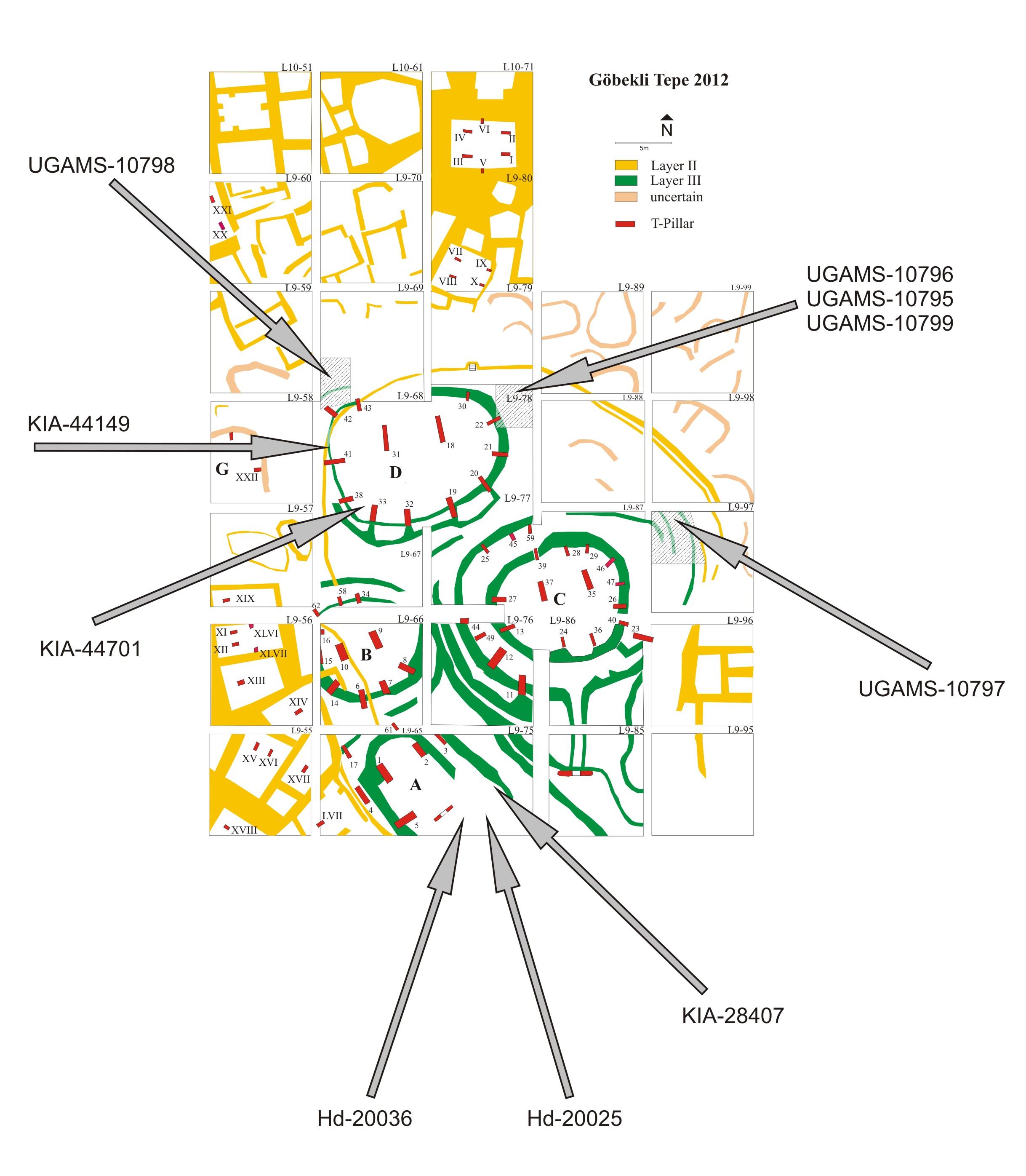

Tabel 2: The main excavation area at Göbekli Tepe with origin of C14 samples (DAI).

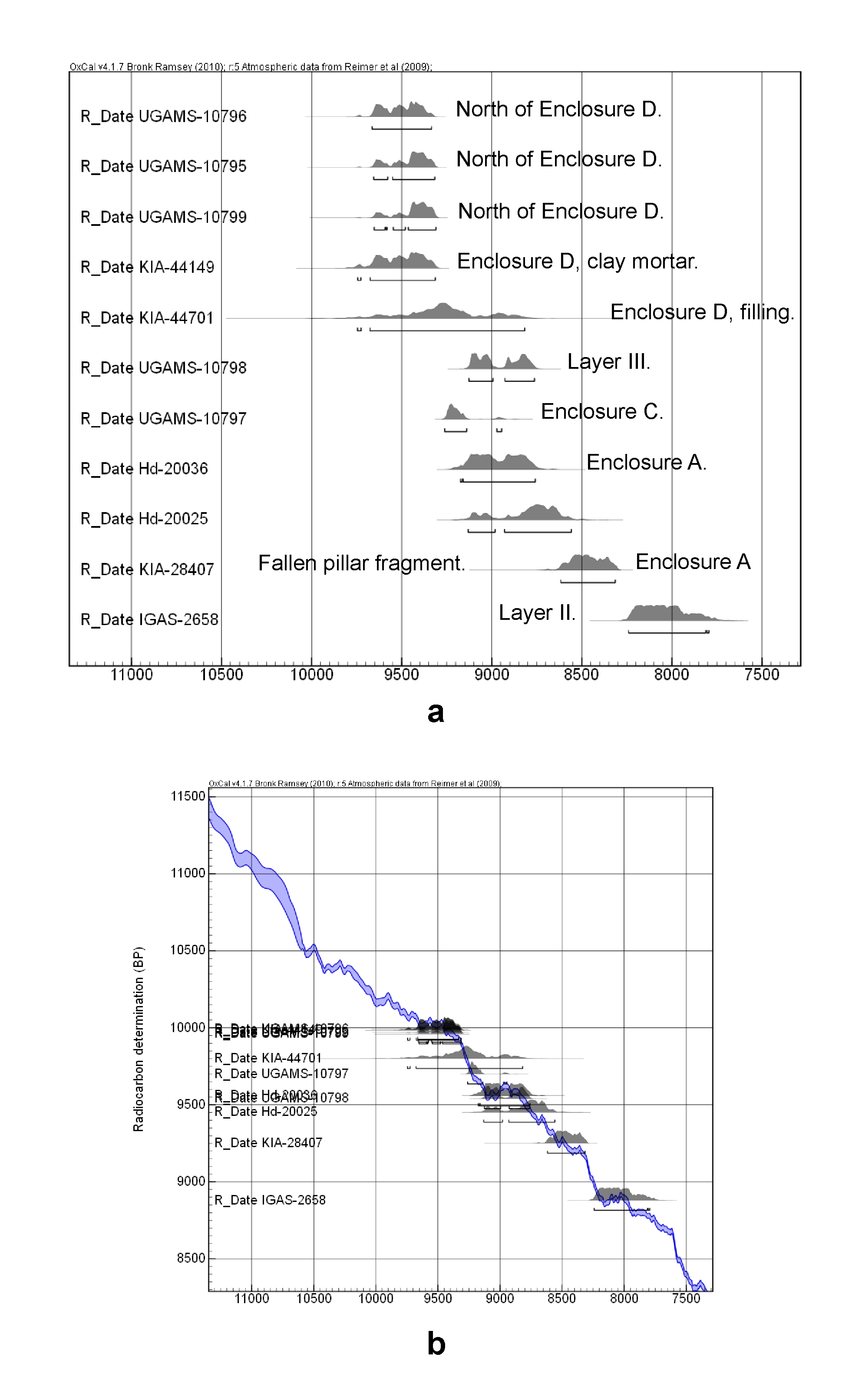

Table 3: Charts of radiocarbon data from Göbekli Tepe (DAI).

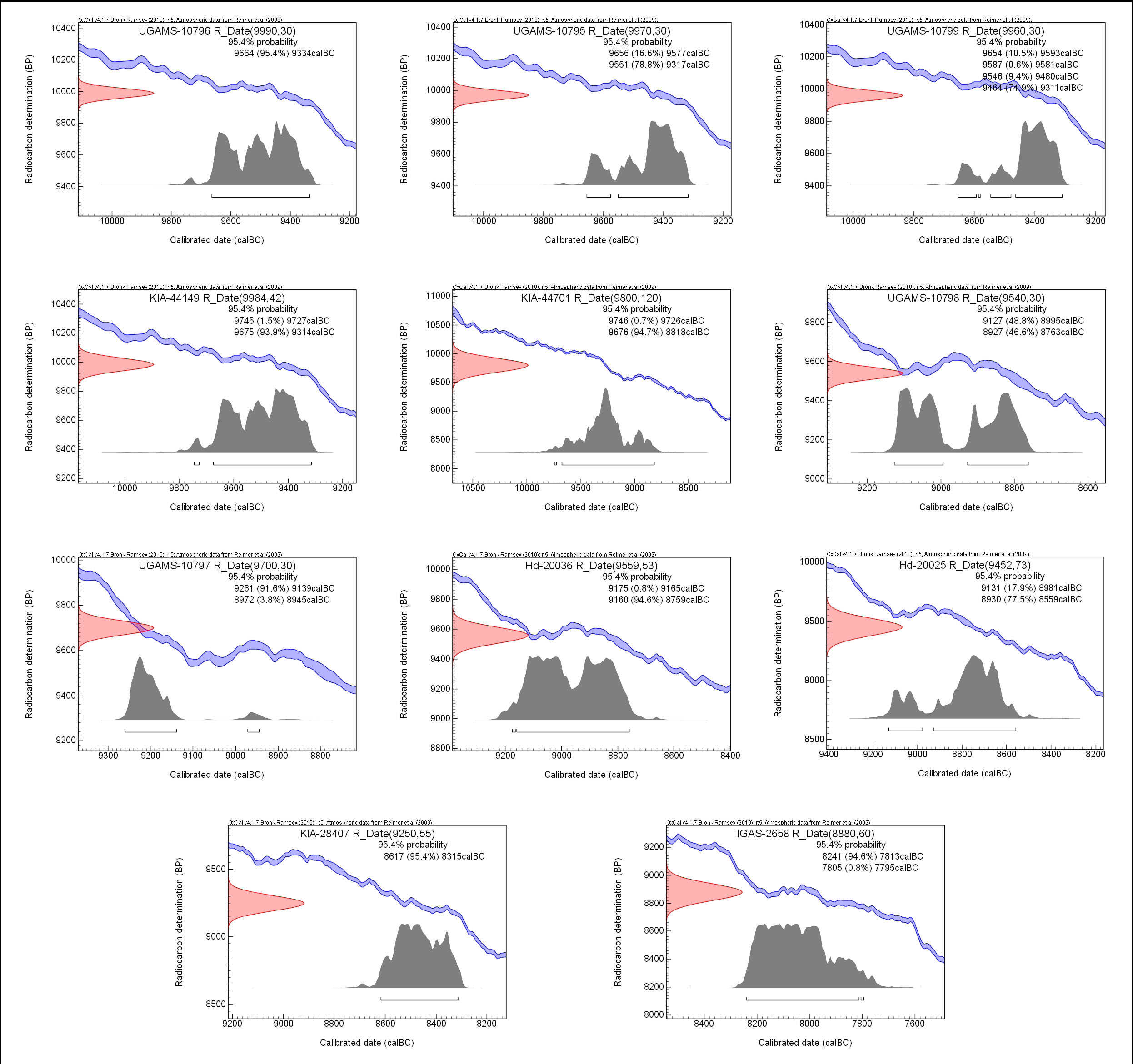

Table 4: The calibrated radiocarbon data from Göbekli Tepe – single plots (DAI).

The period Göbekli Tepe was built in is addressed as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) after one of its main cultural traits, the absence of pottery vessels (there are clay figurines later in the PPN, however). The general chronological division for the Early Neolithic was developed in the Southern Levant, by Kathleen Kenyon on the basis of the stratigraphy of Jericho. She observed a fundamental distinction in the ground plans of buildings – round constructions in the earlier PPN A, rectangular buildings in the later PPN B. She further based her subdivision on differences in the material culture. These differences are most obvious in a certain find category: projectile points. Very detailed categorization schemes have been elaborated meanwhile, based on material from sites throughout the Near East. They serve as ‘guiding fossils’ for dating (yes, early archaeologists borrowed this term from geology).

At Göbekli Tepe, we can differentiate two layers which are completely different in the type of architecture appearing in them. Layer III, the lower and thus older layer, has the famous circular enclosures with the T-shaped pillars. Layer II is characterized by smaller buildings with rectangular groundplans. They sometimes also have pillars that are much smaller than the older ones however.

El-Khiam-, Helwan-, Nemrik- and Byblos-Points from Göbekli Tepe (Photo: Irmgard Wagner, DAI).

Projectile points from Göbekli Tepe include PPN A types like el-Khiam, Helwan and Aswad points; regarding the PPNB, Byblos and Nemrik points are very frequent, Nevalı Çori points are rare. They clearly show that the site was in use beginning from the PPN A and into the PPN B. A closer examination of the points reveals, however, that characteristic forms of the latest PPN B are missing. Göbekli Tepe was abandoned after the middle PPN B, i.e. around 8000 BC. That is the time when agriculture finally is fully established; the demise of a hunter-gatherer site would thus fit in this general picture. There are neither domesticated plants, nor animals at Göbekli Tepe. Radiocarbon data support the general archaeological dating (see below).

Filling material in Enclosure D (Photo: K. Schmidt, DAI).

So far so good, but there is a problem with this story. The enclosures of Layer III were treated in a special way at the end of their use lives. They were cleaned, part of their fittings dismantled, and refilled. During the refilling, objects that obviously had a great importance to PPN people were deposited in the filling [link]. However it seems that refilling was a relatively fast process. There are no intermediate sterile layers brought in by water or wind.

This refilling is fascinating in regard to the enclosure’s functions but poses severe problems for the dating of Layer III using the radiocarbon method, as organic remains from the fill-sediments could be older or younger than the enclosures, with younger samples becoming deposited at lower depths, thus producing an inverse stratigraphy. Another issue is the lack of carbonized organic material available for dating; only in the last campaigns have larger quantities been discovered.

Given these inherent difficulties, in a first approach the attempt was made to date the architecture directly using pedogenic carbonates. These begin to form on limestone surfaces as soon as they are buried with sediment. Unfortunately the pedogenic carbonate layers accumulate at a variable rate over long time periods, so a sample comprising a whole layer will yield only an average value. This problem can be avoided by sampling only the oldest calcium carbonate layer in a thin section: the result should be a date near the beginning of soil formation around the stone, i.e. near the time of its burial. Radiocarbon data are available from both the architecture of Layers III and II. Although the observed archaeological stratigraphy is confirmed by the relative sequence of the data, absolute ages are clearly too young, with Layer III being pushed into the 9th millennium, and Layer II producing ages from the 8th or even 7th millennia calBC. Therefore, the data fail to provide absolute chronological points of reference for architecture and strata. At most they serve as a terminus ante quem for the backfilling of the enclosures (Layer III) and the abandonment of the site (Layer II).

A far better source of organic remains for the direct dating of architectural structures is the wall plaster used in the enclosures. This wall plaster comprises loam, which also contains small amounts of organic material. A sample (KIA-44149, cf. Tables 1-4) taken from the wall plaster of Enclosure D gives a date of 9984 ± 42 14C-BP (9745-9314 calBC at the 95.4% confidence level), thus placing the circle in the PPNA. This approach will be pursued in more detail in the future. A series of 80 samples has already been dated and will be published soon.

Concerning the filling material from the enclosures, two approaches have been pursued, the first dedicated to the dating of animal bones and a second to ages made on charcoal. The archaeological appraisal of a recently acquired series of 20 data made on bone samples is quite complicated as they pose some methodological problems. At least within the group of samples chosen, collagen conservation is poor, and the carbonate-rich sediments at Göbekli Tepe may be the cause for problems with the dating of apatite fractions.

Carbonized plant remains have been very scarce at the site, thus limiting the possibilities for dating charcoal. Nevertheless, three charcoal samples are available for Enclosure A. While two samples (Hd-20025 and Hd-20036, cf. Tables 1-4) stem from back-fill and have been dated to the late 10th / earliest 9th millennium calBC, a third charcoal sample (KIA-28407, cf. Tables 1-4) was taken from beneath a fallen fragment of a pillar. This sample has provided a date for a possible final filling event around the mid-9th millennium calBC. It is confirmed by a measurement (IGAS-2658, cf. Tables 1-4) made on humic acids from a buried humus horizon that provides a terminus ante quem for Layer II in area L9-68, dating to the late 9th / early 8th millennium calBC.

Larger amounts of carbonized material have been discovered in deep soundings excavated in preparaiton of the construction of permanent shelter structures over the site in recent years. Two deep soundings were excavated directly adjacent to the ring wall belonging to Enclosure D, with three new ages obtained from charcoal recovered from the sounding in area L9-78. These samples were collected close to the bedrock, which in its interior forms the floor of this enclosure. Calibrated ages cluster between 9664 to 9311 calBC at the 95.4% confidence level (UGAMS-10795, 10796, 10799, cf. Tables 1-4), a time-span which is in good agreement with the earlier measurement made on clay mortar from the ring wall of Enclosure D between Pillars 41 and 42 (KIA-44149, 9984 ± 42 14C-BP, 9745-9314 calBC at the 95.4% confidence level, cf. Tables 1-4). Based on these data, we now have a much clearer picture of the chronological frame within which construction activities took place in the area of Enclosure D. It is only regrettable that these four data all correspond to a period with a slight plateau in the calibration curve, thus resulting in larger probability ranges. Additional excavation work is needed to clarify the exact stratigraphical correlation of the three new charcoal dates with Enclosure D.

Finally, from the filling material of Enclosure D there is one new 14C-age made on collagen from an animal tooth found north of Pillar 33 (KIA-44701, 9800 ± 120 14C-BP, 9746-8818 calBC at the 95.4% confidence level, cf. Tables 1-4). Taken together with another new measurement made on charcoal extracted from the same fill (Layer III) in area L9-69 (UGAMS-10798, 9540 ± 30 14C-BP, 9127-8763 calBC at the 95.4% confidence level, cf. Table 1-4) there can still be no consensus regarding the time of abandonment and burial of this enclosure. Further radiocarbon measurements will be needed to clarify this process. Indeed, the animal tooth used to produce sample KIA-44701 (cf. Table 1) might even come from the enclosue’s use-life which, as we know, would have included the celebration of large feasts [link]. This line of thought would then allow for a considerable time (i.e. several hundred years) of use of the enclosure prior to its burial sometime in the late 10th or early 9th millennium calBC (UGAMS-10798, cf. Tables 1-4). But at the moment a rather short life-span of the enclosure remains possible too. At this point, reference should again be made to sample IGAS-2658 (8880 ± 60 14C-BP, 8241-7795 calBC at the 95.4% confidence level, Table 1-4) taken from a humus layer in area L9-68. This date marks the last PPN activities in this area and provides a terminus ante quem for Layer II.

To present, only one date is available for Enclosure C (UGAMS-10797, 9700 ± 30 14C-BP, 9261-9139 calBC at the 91.6% probability level, cf. Table 1-4). This sample was taken from a deep sounding in area L9-97 between the outermost ring walls of the enclosure and close to the bedrock. This could indicate that building activities at the outer ring walls of this enclosure were underway during the backfilling of Enclosure D. However, a larger series of data and a close inspection of Enclosure C´s building history will be necessary to confirm such far-reaching conclusions.

As a preliminary conclusion, the still limited series of radiocarbon data seems to suggest that the Layer III enclosures at Göbekli Tepe were not exactly contemporaneous. Earliest radiocarbon dates stem from Enclosure D, for which the relative sequence of construction (ca. mid-10th millennium calBC), usage, and burial (late 10th millennium calBC) are documented. The outer ring wall of Enclosure C could be younger than Enclosure D. However, more data are needed to confirm this interpretation. Finally, Enclosure A seems younger than Enclosures C and D. With only eleven radiocarbon dates, many questions remain for the moment that our new series of data will hopefully answer.

Further Reading

B. Kromer, K. Schmidt, Two Radiocarbon Dates from Göbekli Tepe, South Eastern Turkey, Neo-Lithics 3/98, 1998, 8–9.

O. Dietrich, C. Köksal-Schmidt, J. Notroff, K. Schmidt, Establishing a Radiocarbon Sequence for Göbekli Tepe. State of Research and New Data, Neo-Lithics 1/2013, 36-41.

Göbekli Tepe´s material culture

K. Schmidt, Göbekli Tepe. Southeastern Turkey. A Preliminary Report on the 1995-1999 Excavations, Paléorient 26/2001, 45-54.

Dating of animal bone

O. Dietrich, Radiocarbon dating the first temples of mankind. Comments on 14C-Dates from Göbekli Tepe. Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 4, 2011, 12-25.

Dating of pedogenic carbonates

K. Pustovoytov, 14C Dating of Pedogenic Carbonate Coatings on Wall Stones at Göbekli Tepe (Southeastern Turkey). Neo-Lithics 2/2002, 3-4.

K. Pustovoytov, H. Taubald, Stable Carbon and Oxygen Isotope Composition of Pedogenic Carbonate at Göbekli Tepe (Southeastern Turkey) and its Potential for Reconstructing Late Quaternary Paleoenviroments in Upper Mesopotamia. Neo-Lithics 2/2003, 25-32.

K. Pustovoytov, K. Schmidt, H. Parzinger, Radiocarbon dating of thin pedogenic carbonate laminae from Holocene archaeological sites. The Holocene 17. 6, 2007, 835-843.

Dating of mud plaster

O. Dietrich, K. Schmidt, A radiocarbon date from the wall plaster of enclosure D of Göbekli Tepe, Neo-Lithics 2/2010, 82-83.

Recent Comments