Earlier this year we organised a session at the European Association of Archaeologists annual conference which was held in Maastricht (Netherlands) this year. Already in this session’s title we asked contributors and audience the crucial question “What is so special about Neolithic special buildings?” – and we had quite a broad spectrum of approaches to this topic and discussed many possible charactersitics (alas, as often in research we just could not find the one all-embracing answer – but to be honest, no-one really expected this).

Dr Anna Fagan from the University of Melbourne, who did her PhD on “Relational Ontologies in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Middle East” in 2016, was one of the colleagues presenting in our session and contributing to this discussion. She kindly agreed to recapitulate and sum up her PhD research published earlier in World Archaeology for a guest blogpost and we are pleased to share her contribution here:

Hungry Architecture: Spaces of Consumption and Predation at Göbekli Tepe

The excavations of Göbekli Tepe by the German Archaeological Institute over the last two decades have unearthed an unprecedented and as yet unparalleled level of monumental art and architecture, constructed by hunting-and-gathering human groups prior to the full adoption of agriculture. The astonishing and unexpected nature of the finds has driven home the need for more suitable interpretative frameworks that can make sense of the diversity and unfamiliarity of the prehistoric past. Indeed, preceding discussions of the site have served only to further the distance between now and the Neolithic through strict reliance on modern Western concepts that in prehistory would surely have been unimaginable. Hence, in order to come closer to understanding other societies and archaeologies, we must turn to ways of thinking that do not replicate the dominant and historically specific Western ontology.

Engagement with non-Western thinkers and ethnographies reveals the conceptual potential of different modes of thought, metaphysics, and ways of being. Taking other systems of knowledge on equal intellectual terms is not only a matter of political exigency, but also constitutes a more holistic, reflexive, and critical archaeology. For instance, innumerable human groups around the globe describe realities wherein personhood and social relations are not exclusive to humans. Instead, animals, plants and material life can potentially act as subjects, with consciousness, agency and intentionality.

By liberating thought from Western metaphysical foundationalism, we become aware of the inadequacy of modern Western theories of matter to explain the prehistoric world fully. Paying attention to the phenomenal and ontological dimensions of the Göbekli architecture reveals limestone to be an agentive materiality from which powerful entities were released and brought into being through the practices of carving. It was likely that highly volatile gods, spirits and animals occupied the socio-cosmic universe of prehistoric south-east Anatolia. Through depicting these powerful or threatening agencies, people set up channels of engagement through which they could interact with dangerous entities on their own terms, affording participants a rare degree of controlled interaction in the existentially risky realm of the spirit world.

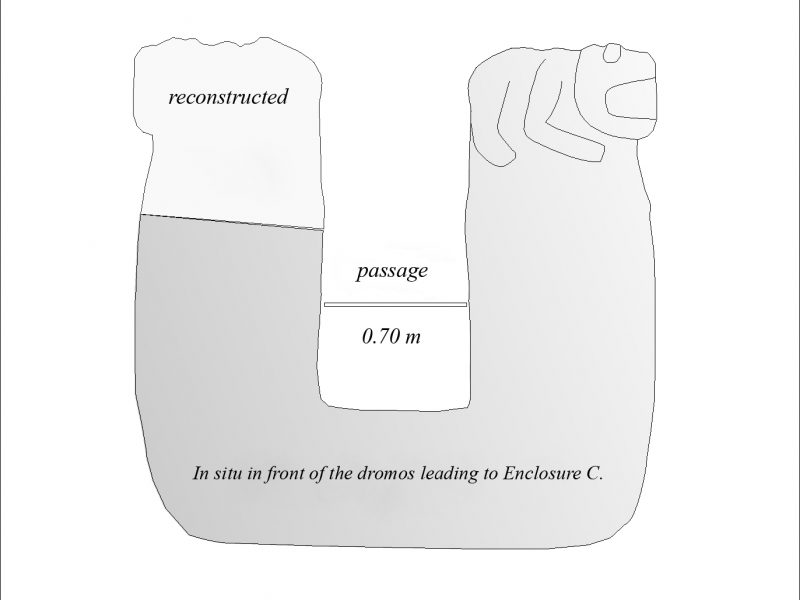

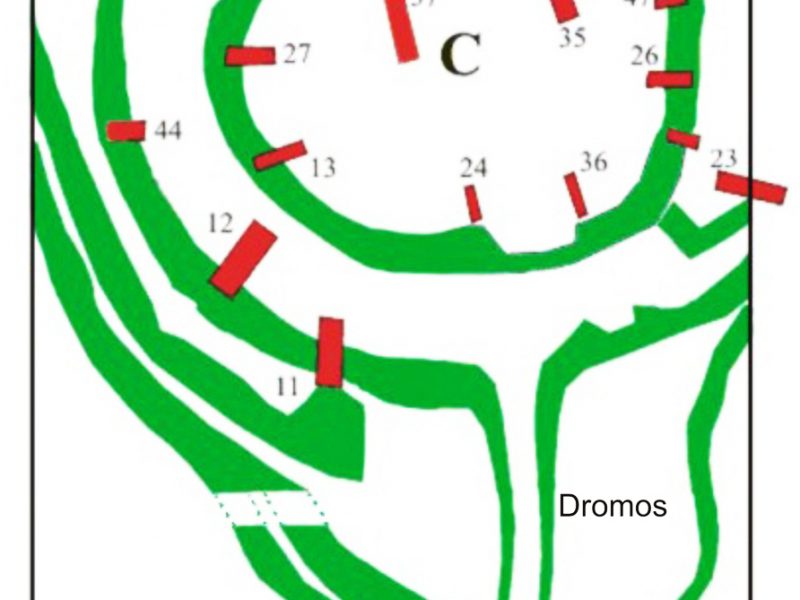

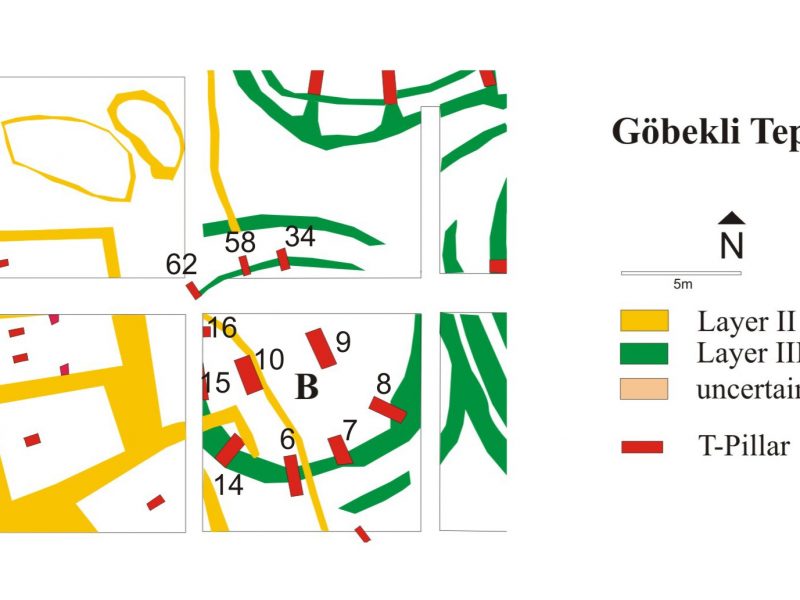

However, this does not mean that T-pillars and statuary remained static entities; rather, they may have been capable of movement, absence or transformation. As demonstrated by finds of offering bowls and channels for libations, these beings might have been animated – or tempered – by consumption. Indeed, Göbekli challenges conventional conceptual commitments to permanence, fixity and finality. Practices of image-creation and monument construction at the site seem more committed to processes of making than finished production. Stelae are installed in incomplete states or are reworked into new forms and enclosures were subject to considerable modifications in structure and layout throughout their use-lives. In Enclosure C, for instance, walls with embedded pillars were later engulfed by additional internal walls, stelae and installations, shrinking the circumference of the building through time. With each building phase, artefacts, offerings, skeletal remains, and sculptures were ‘fed back’ into the structural fabric. These labour-intensive changes along with the cumulative wrapping of the space seem to articulate efforts to entrap, engulf, and contain. We might even consider the Göbekli enclosures to be mouths of a sort: cavernous cavities with enormous T-pillar teeth, teeming with statuary of ravenous predators.

The notion that the limestone from which Göbekli is built constituted a vital and even ‘hungry’ materiality may be further explored through practices pertaining to stone extraction. For instance, the infill for the enclosures appears to have been stored on site to be used later, suggesting that these remains retained a special quality separate from other types of settlement waste (Dietrich, Notroff and Schmidt 2017, 119). The fact that the infill consists primarily of animal remains and limestone rubble might indicate where it was stored prior to burial, and with the quarries in close proximity, they present a viable option. If we consider limestone as alive – and thus the process of stone extraction to have been existentially risky – depositing feasting deposits in extraction hollows may have served as ritual offerings for relocated stones. Hollows in the quarry presented metaphysical voids that needed to be addressed and recompensed. Thus, through feasting and depositional practices, the rock was duly ‘fed’.

Indeed, predation and consumption seem to be the key ontological principles driving social engagements at the site. Images of decapitated human heads in the clutches of raptors or predators are common at Göbekli, suggesting that the site may have functioned, amongst other things, as a mortuary sphere where raptors potentially defleshed and disposed of the dead (as in Tibetan sky burials, Zoroastrian funerals, the mortuary practices of the Kwakiutl of British Columbia and of the Chukchi of northern Kamchatka). It was conceivably through predatory consumption of the deceased that the human soul was released, flesh transmuted into spirit matter, and vitality redistributed from the consumed to the consumer. The possibility that Göbekli served as a necropolis is supported by the considerable number of human bone fragments with evidence of partial burning, along with cut-marks denoting defleshing and other post-mortem ritual treatments uncovered from the enclosure fills (Becker et al. 2012; Notroff et al. 2016, 78). Moreover, necrophagous animals are common in the osteoarchaeological and iconographic corpus. Corvids, for instance, make up more than 50 per cent of the avifauna from the site, a number significantly higher than at other contemporaneous settlements (Peters et al. 2005, 231; Notroff, Dietrich and Schmidt 2016, 77–8). Furthermore, the common practice of decapitating anthropomorphic sculpture at the site may even have served as a proxy for the cessation and transformation of human life. Just as vultures assisted in humans’ ontological metamorphosis, so too might practices of decapitation have released the deceased from the confines of the human corpse (Fig. 1).

Göbekli Tepe: the only example of a decapitated limestone head where a matching torso was found (photo: N. Becker, German Archaeological Institute).

However, while humans are commonly found in decapitated and diminutive forms, predatory animals are portrayed as frighteningly alive, voracious and present. The human face, too, remains schematic and tokenistic, while the animal face is highly detailed. One striking example of a ravenous predator comes from Pillar 27 in Enclosure C (Fig. 2), consisting of a three-dimensional high relief of a large, expertly crafted reptile, with unmistakably delineated ribs and bared teeth, descending the side of the stele.

Göbekli Tepe: Enclosure C. A snarling and hungry three-dimensional predator with clearly delineated ribs descends pillar 27 (photo: D. Johannes, German Archaeological Institute).

The images of predators holding dislocated human heads, in conjunction with the evidence of intensive feasting found at the site (Dietrich et al. 2012), the remains of human bone uncovered in the enclosures’ fill, along with the high number of corvids (crows and ravens) in the avifauna evince a co-productive relationship: of animals feeding on humans and vice versa. Finds of stone bowls and depressions, located next to the central pillars in the enclosures, demonstrate that the megalithic T-pillar beings, too, not only had demands, but were capable of consumption. However, themes of death and predation at Göbekli should not be perceived as destructive but rather, co-productive. Manifest is the network of relations upon which life itself depends: the cycle of death, consumption and reproduction.

Through feeding and bringing into being volatile agencies at Göbekli Tepe, people may have aided the transformation and metamorphosis of the dead and opened up channels of engagement through which the living could influence the spirit world. Convening with powerful beings in the confines of these spiritually fortified spaces afforded humans a degree of control and perhaps even the ability to harness their predatory perspectives (see: Fagan 2016, 2017). Similarly, it is new perspectives – ones that do not replicate the dominant Western ontology – that should travel to archaeological interpretation, so that we too, can engage a more sensitive relationship with the past.

For a longer and more detailed discussion of the phenomenal and ontological dimensions of the art, architecture, and osteoarchaeological finds from Göbekli Tepe, see Anna’s original article (and references therein) in World Archaeology 49.3, 2017 [external link].

You can learn more about Anna’s work and research through her profile at academia.edu [external link] or find her on twitter [external link].

References

Becker, N., O. Dietrich, T. Götzelt, Ç. Köksal-Schmidt, J. Notroff, and K. Schmidt. 2012. “Materialien zur Deutung der zentralen Pfeilerpaare des Göbekli Tepe und weiterer Orte des obermesopotamischen Frühneolithikums.” Zeitschrift für Orient Archäologie 5: 14–43.

Dietrich, O., M. Heun, J. Notroff, K. Schmidt, and M. Zarnkow. 2012. “The Role of Cult and Feasting in the Emergence of Neolithic Communities: New Evidence from Göbekli Tepe, South-Eastern Turkey.” Antiquity 86: 674–695. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00047840.

Dietrich, O., J. Notroff, and K. Schmidt. 2017.“Feasting, Social Complexity, and the Emergence of the Early Neolithic of Upper Mesopotamia: A View from Göbekli Tepe.” Feast, Famine, or Fighting?: Multiple Pathways to Social Complexity, edited by R. J. Chacon and R. G. Mendoza, 91–132. Cham: Springer International Publishing. (Studies in Human Ecology and Adaptation 8).

Fagan, A. 2016. Relational Ontologies in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Middle East. PhD Diss. University of Melbourne.

Fagan, A. 2017. “Hungry Architecture: Spaces of Consumption and Predation at Göbekli Tepe,” World Archaeology 3:318-37.

Notroff, J., O. Dietrich, and K. Schmidt. 2016. “Gathering of the Dead? The Early Neolithic Sanctuaries of Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey.” In Death Shall Have No Dominion: The Archaeology of Mortality and Immortality – a Worldwide Perspective, edited by C. Renfrew, M. Boyd, and I. Morley, 65–81. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Peters, J., A. Driesch, A. Von Den, and D. Helmer. 2005. “The Upper Euphrates: Tigris Basin, Cradle of Agropastoralism?” In The First Steps of Animal Domestication, edited by J. D. Vigne, J. Peters, and D. Helmer, 96–124. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

(Opinions and interpretations expressed in guest contributions on this blog do not necessarily need to reflect those of the research team or the German Archaeological Institute.)

Recent Comments