We have finally published some thoughts on processing and use of cereals at Göbekli Tepe. As the text is open access, we will just leave the link , some beautiful images of phytoliths, use-wear and grinding stones as well as the abstract here:

Dietrich L, Meister J, Dietrich O, Notroff J, Kiep J, Heeb J, Beuger A, Schütt B (2019) Cereal processing at Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Turkey. PLOS ONE 14(5): e0215214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215214

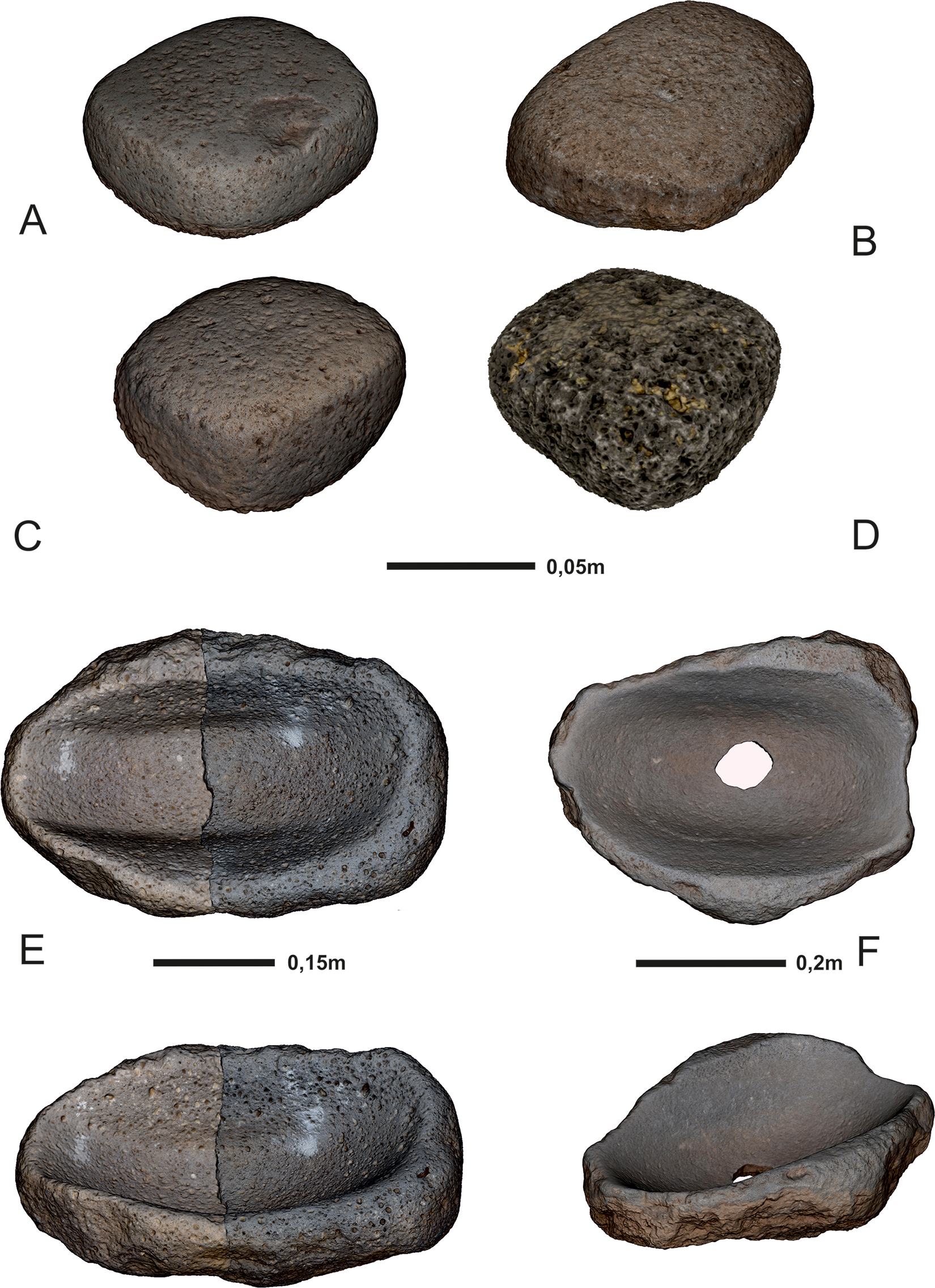

Grinding tools from Göbekli Tepe. (A), (C) Neolithic handstones of type 1; (B) Neolithic handstone of type 2; (D) Experimental handstone of type 1, produced as copy of (C); (E, F) Neolithic grinding bowls (German Archaeological Institute, 3D-models H. Höhler-Brockmann and N. Schäkel).

Abstract

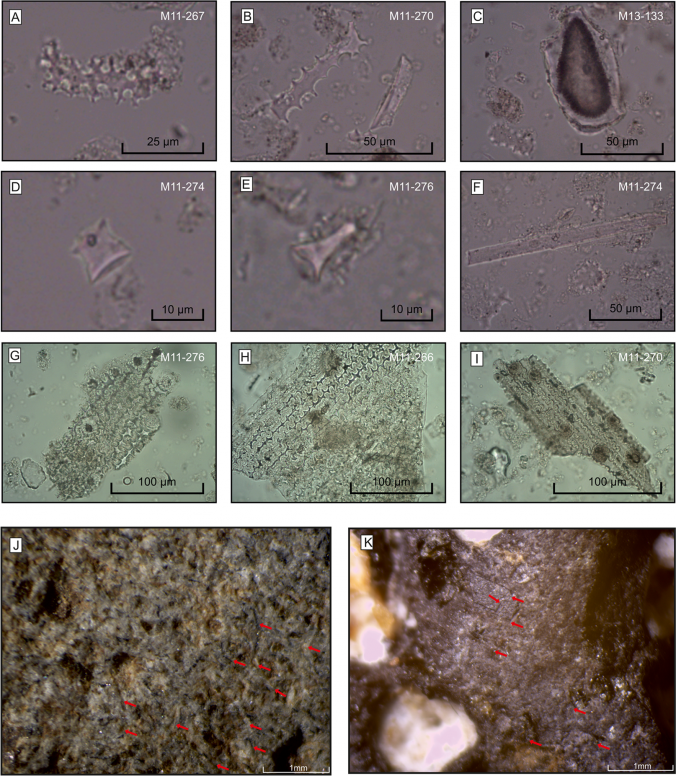

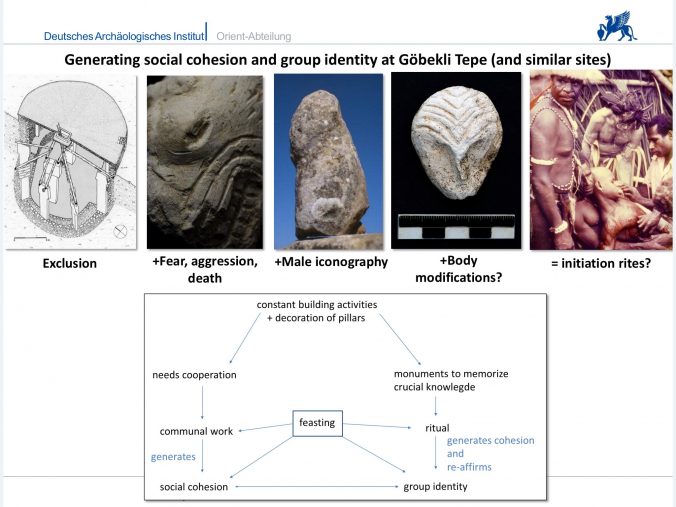

We analyze the processing of cereals and its role at Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Anatolia (10th / 9th millennium BC), a site that has aroused much debate in archaeological discourse. To date, only zooarchaeological evidence has been discussed in regard to the subsistence of its builders. Göbekli Tepe consists of monumental round to oval buildings, erected in an earlier phase, and smaller rectangular buildings, built around them in a partially contemporaneous and later phase. The monumental buildings are best known as they were in the focus of research. They are around 20 m in diameter and have stone pillars that are up to 5.5 m high and often richly decorated. The rectangular buildings are smaller and–in some cases–have up to 2 m high, mostly undecorated, pillars. Especially striking is the number of tools related to food processing, including grinding slabs/bowls, handstones, pestles, and mortars, which have not been studied before. We analyzed more than 7000 artifacts for the present contribution. The high frequency of artifacts is unusual for contemporary sites in the region. Using an integrated approach of formal, experimental, and macro- / microscopical use-wear analyses we show that Neolithic people at Göbekli Tepe have produced standardized and efficient grinding tools, most of which have been used for the processing of cereals. Additional phytolith analysis confirms the massive presence of cereals at the site, filling the gap left by the weakly preserved charred macro-rests. The organization of work and food supply has always been a central question of research into Göbekli Tepe, as the construction and maintenance of the monumental architecture would have necessitated a considerable work force. Contextual analyses of the distribution of the elements of the grinding kit on site highlight a clear link between plant food preparation and the rectangular buildings and indicate clear delimitations of working areas for food production on the terraces the structures lie on, surrounding the circular buildings. There is evidence for extensive plant food processing and archaeozoological data hint at large-scale hunting of gazelle between midsummer and autumn. As no large storage facilities have been identified, we argue for a production of food for immediate use and interpret these seasonal peaks in activity at the site as evidence for the organization of large work feasts.

Recent Comments