We were asked in comments and messages to elaborate some more on the contents of our recent paper. So here is a short summary of the article recently published in PLoS ONE. For more information on the findings outlined here, please consult the original publication:

Dietrich L, Meister J, Dietrich O, Notroff J, Kiep J, Heeb J, et al. (2019) Cereal processing at Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Turkey. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0215214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215214

Cereal food is one of the most important components of our modern diet. Its integration into human subsistence strategy during the late Epipalaeolithic (c. 12500–9600 cal BC) and Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN, c. 9600–7000 cal BC) has been recognized as a very long and complex process involving the selection and utilization of plants, strategies of exploitation of plants and land, the development of cultivation, and ways of processing, storing, and consuming plants. Widespread adoption of farming and agriculture at the end of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPNB, c. 8800–7000 cal BC), the deliberate, large-scale cultivation of domesticated cereals and other plants, was predated by a longer period of experimentation and technological modification leading to the development of specialized tool kits for plant-food processing. Typical implements are e.g. pounding and grinding tools used in pairs, comprising a static low implement (mortar, grinding slab or grinding bowl) and an active upper tool that is moved across its surface (pestle or handstone).

Cereal use in the Early Neolithic

The regular processing of wild cereals through grinding seems to have been established first in the Late Natufian, as suggested by macrobotanical evidence as well as by morphological changes in grinding stones combined with use-wear analyses. Flat, large grinding stones and handstones became a supra-regional standard during the Levantine PPN, constituting an integral part of the architecture. Recent investigations have highlighted the area between the upper reaches of Euphrates and Tigris as one region where the transition to food-producing subsistence took place early during the Epipalaeolithic and the Pre-Pottery Neolithic. The distribution areas of the wild forms of einkorn, emmer wheat, barley and other ‘Neolithic founder crops’ overlap here and DNA fingerprinting has pinpointed the transition of two wild wheat variants to domesticated crops to this part of the Fertile Crescent. Systematic early plant use has been found at a variety of sites, like Cafer Höyük, Çayönü, Hallan Çemi, Jerf el Ahmar or Körtik Tepe.

Göbekli Tepe has not played any role in discussions of early cereal use so far. The reasons can be found – at least in part – in the problematic nature of direct evidence for cereals on site. Although analysis of macrobotanical remains indicates the presence of wild einkorn (Triticum cf. boeticum/urartu), wild barley (Hordeum cf. spontaneum) and possibly wild wheat/rye (Triticum/Secale), as well as almonds (Prunus sp.) and pistachio (Pistacia sp.) at Göbekli Tepe, only a conspicuously low amount of carbonized plant remains has been recovered, both in handpicked and in flotation samples.

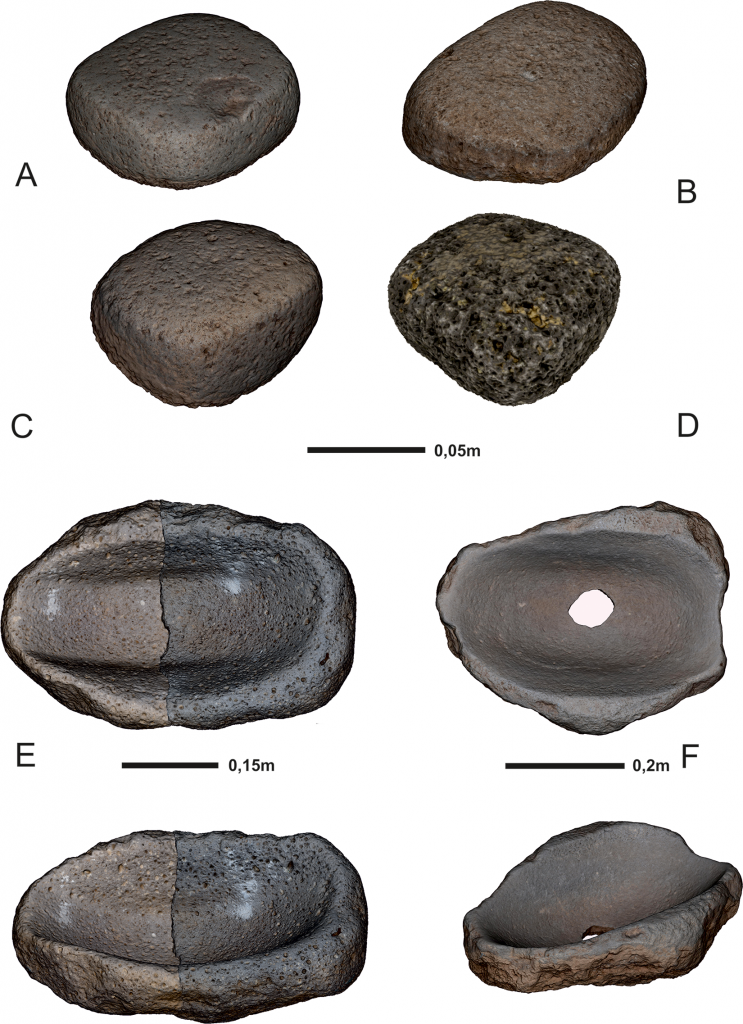

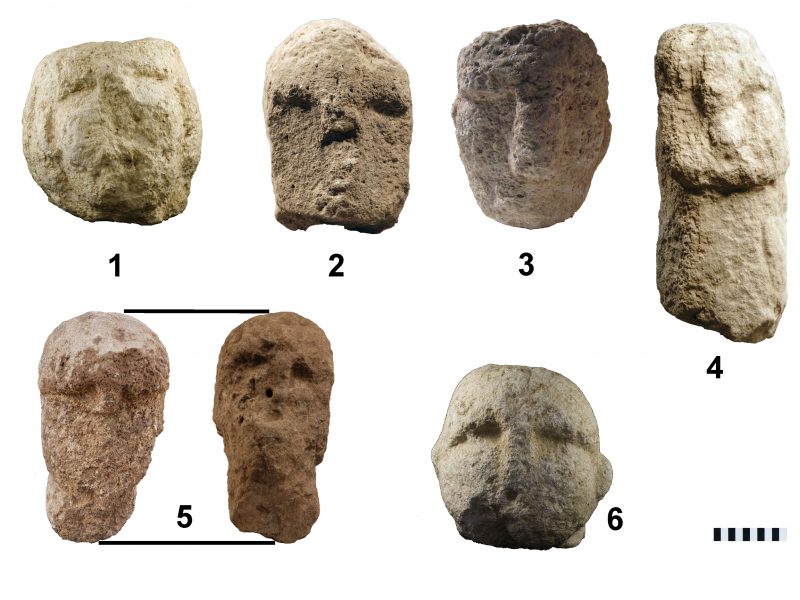

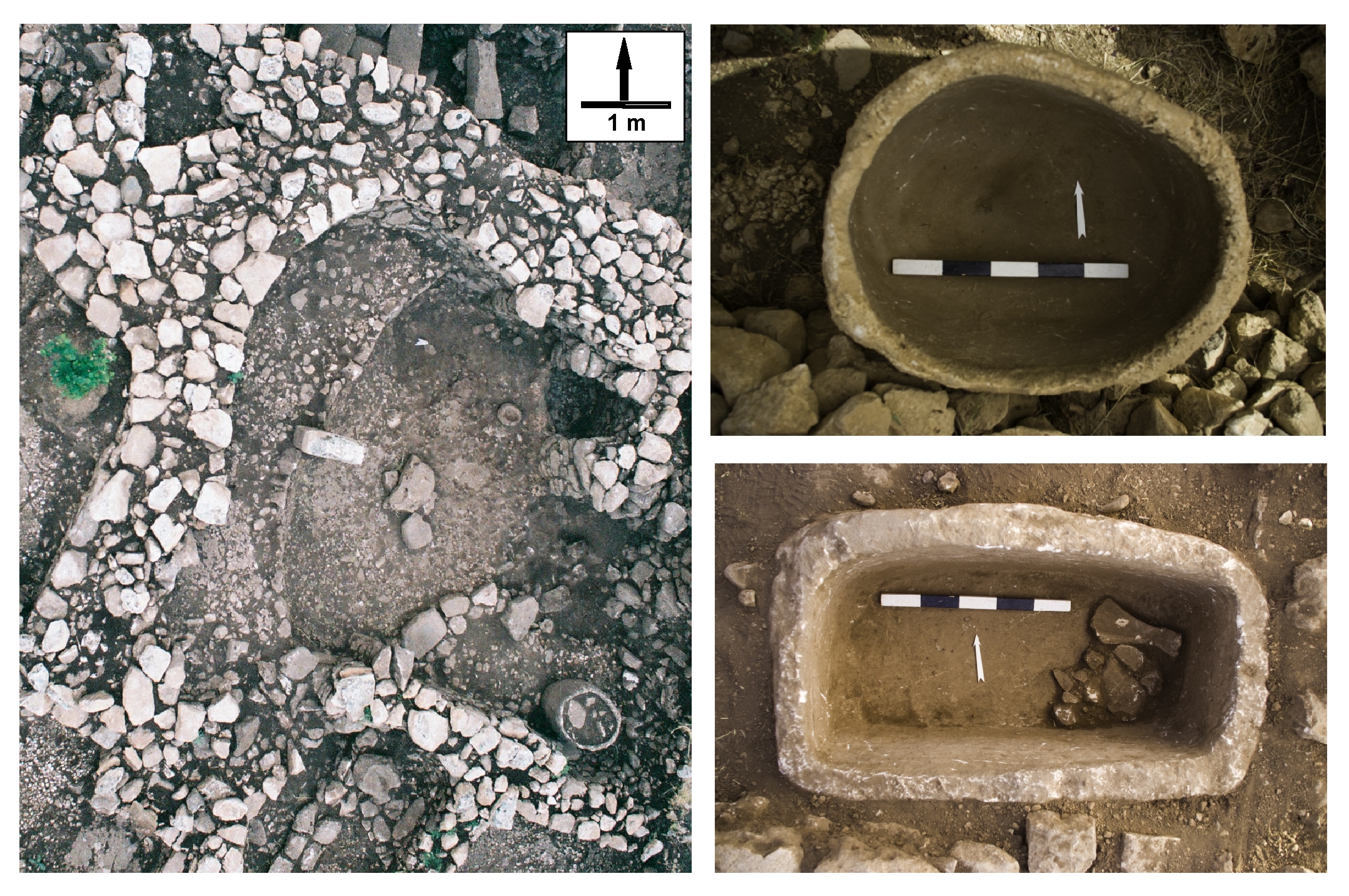

Grinding tools from Göbekli Tepe. (A), (C) Neolithic handstones of type 1; (B) Neolithic handstone of type 2; (D) Experimental handstone of type 1, produced as copy of (C); (E, F) Neolithic grinding bowls (German Archaeological Institute, 3D-models H. Höhler-Brockmann and N. Schäkel).

However, Göbekli Tepe has not only produced an impressive set of architecture – monumental round to oval buildings with T-shaped limestone pillars, erected in an earlier phase, and smaller rectangular buildings, built around them in a partially contemporaneous and later phase – but also a unusually large number of over 7000 grinding tools. We analyzed these tools using an integrated approach of formal, experimental, and macro- / microscopical use-wear analyses.

Göbekli Tepe

As a first step in our analysis we had to determine the functional variation of these grinding tools, as a wide range of uses is attested archaeologically and ethnographically, ranging from cereal processing to pounding of meat or crushing of minerals. Grinding and pounding equipment from Göbekli Tepe was documented through 3D-modelling by structure from motion, and surfaces were macro- and microscopically analyzed for use-wear. We used replicas of the equipment identified on site to experimentally grind different materials and establish a reference collection for the identification of the observed traces. Further, phytolith samples taken from the sediments inside and outside buildings at Göbekli Tepe and from grinding stone surfaces allowed us to determine and quantify the presence of plants. Phytoliths were abundant in all nine soil samples examined, ranging from 0.5 to 3.0 million phytoliths per gram of sediment. Grass phytoliths were the most common group identified. The sediments inside the rectangular buildings largely contain markers for the upper and middle part of plants. This could be indicative of harvested cereals, as plants are usually collected and transported in sheaves. To contextualize the results, we assessed the spatial distribution of grinding equipment and identified potential activity areas.

We found that the most common types of handstones used at Göbekli Tepe show use-wear traces connected to cereal processing. Handstones with such traces concentrate in some of the rectangular buildings, but even more so in open spaces between and around them and the (at least partly) contemporary monumental round structures.

Building D was taken as a case study to asses grinding stone use within the latter. There, grinding equipment from the deepest layer, which appears to be connected to the partially intentional refilling of the structure, also shows traces of ochre, indicating its processing in this structure.

The overall quantity of 7268 analyzed grinding tools from Göbekli Tepe appears to be too high for simple daily use, given their relatively high productivity. A single handstone of the most common types could have produced an average of 4800 g flour within eight working hours, as our experiments show. If we assume that one person needs between 500 g and 1000 g of cereals daily as nutrients for survival, this amount would be enough to feed five to ten people.

Interpretation

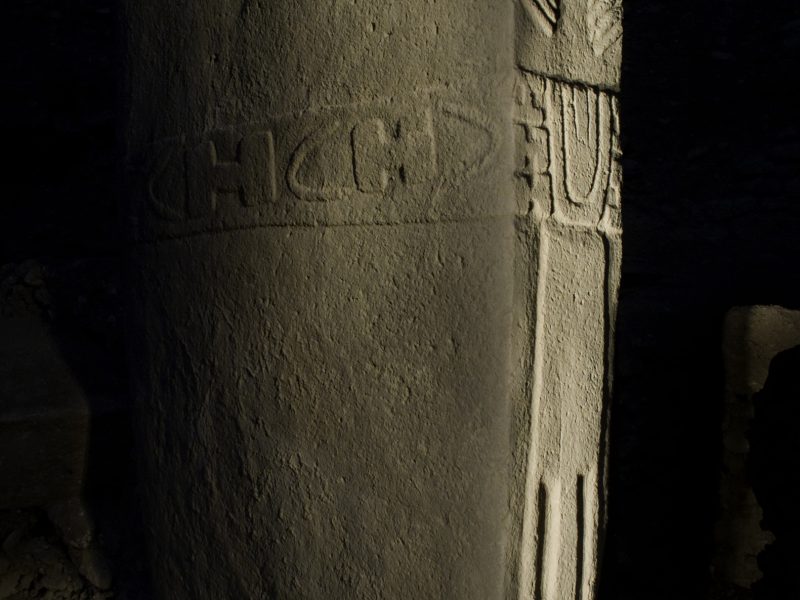

The organization of work and food supply has always been a central question of research into Göbekli Tepe, as the construction and maintenance of the monumental architecture would have necessitated a considerable work force. Göbekli Tepe has a high concentration of distinctive architecture, often addressed as ‘special buildings’, which do not repeat the characteristic plans of domestic buildings from contemporaneous settlements. Extensively excavated settlement sites like Nevalı Çori or Çayönü have one ‘special building’ per settlement phase, while Göbekli Tepe has several, likely contemporary buildings of this type, which different groups of people likely used. For the buildings excavated so far, we have observed certain regularities governing the decoration of the 69 known pillars–mostly with animal motifs, but also with abstract signs. While in building A snake images prevail, in building B foxes are dominant. In building C boar take over, and in building D the imagery is more diverse with birds, especially vultures, playing a significant role. In building H felines are of importance. We see these differences in figurative expression as evidence for different groups of people ornamenting the buildings with the emblematic animals central to their group identities. The site has also produced a wide range of stationary and portable art, far outnumbering such finds from other contemporary sites. Many of the animal and human depictions are clearly marked as male, there are almost no clearly recognizable female depictions, a situation contrary to the materials known from settlements.

At the same time, Göbekli Tepe´s remote location on a barren mountain ridge is very unusual compared to the setting of contemporaneous Neolithic settlements, which are regularly located next to water sources. The construction of monumental architecture at Göbekli Tepe, and other similar sites in its vicinity, would have necessitated a workforce of hundreds of people even by conservative estimates. One model to explain cooperation in small-scale communities involves ritualized work feasts. M. Dietler and E. Herbich define work feasts as events in which “commensal hospitality is used to orchestrate voluntary collective labour,” the incentive to work together is provided by the prospect of large amounts of food and drink. The main archaeological marker for feasting would be evidence of the presence of larger amounts of foodstuffs and tools than needed by the inhabitants of a site for their subsistence. Through our analysis, we have identified evidence for Göbekli Tepe that fits that pattern for plant food. As no large storage facilities have been identified, we argue for a production of food for immediate consumption and interpret these seasonal peaks in activity at the site as evidence for the organization of large work feasts. This adds to archaeozoological data suggesting large-scale hunting of migratory gazelle between midsummer and autumn.

Recent Comments