Yesterday, July 29th was this year’s “Day of Archaeology” [external link] – a project aiming to “… provide a window into the daily lives of archaeologists from all over the world.” Happy to be invited to contribute as well, we thought to share some impressions from a typical day excavating at Göbekli Tepe – ‘just another day in the (field) office’ so to say …

4.30 o’clock. Ante meridiem. Definitely too early for an honest “Good morning.” not pressed through clenched teeth. It’s still dark outside, the dim light barely enough to distinguish a black thread from a white one: The muezzin just called the faithful to prayer and, probably unintentionally, the archaeologists to finally get up as well. Breakfast at such an early hour basically consists of not more than some strong tea, a slice of soft white flatbread (which will be rather dry within the hour), and a handful of olives – taken in the quiet and still fresh morning air of the excavation house’s courtyard in the light of setting stars and a single light bulb. Actually, it’s too early for an honest breakfast too.

The next 20 minutes or so expedition’s staff is silently gathering over tea and bread in dining room and yard before it is time to go. For work, finally. On leaving the historic oriental brick-house in the old part of this eastern Anatolian town, everyone grabs a piece of equipment or provisions for the day to come and one after another heads through the narrow alleys towards the waiting mini bus and driver. A 20-minutes-ride through yet still abandoned streets lies ahead – to the excavation site outside and beyond town. The last chance for a nap.

To work. Through dim alleyways. (Photo: J. Notroff)

As we arrive on this early Neolithic site, somewhere up in the mountains of southeastern Turkey, a pale moon is still hanging around a sky only slowly changing from black to blue. Groups of local workmen just arrived minutes before by tractor from a village down the hill. Still dressed in coats and cardigans against the morning coolth, they are waiting for day’s work to start while the bunch of students and scientists are collecting tools and instruments, equipment and journals. Finally, first light is sounding the bell for the workday to start as a still shy sun is hesitantly peeking above the eastern horizon. Workmen and archaeologists alike are heading to the excavation trenches, a caravan of shovels and buckets, of head-scarves and hats. Everyone knows his place and assignment; gangs finding together following a long-established system (and dare you trying to change this!): There’s two diggers, a shoveller, and two basket-carriers. Always. All of them accompanied by a student ready to label, note, and measure any find of interest they may unearth.

Early birds. (Photo: J. Notroff)

Soon the air is filled with the sound of pickaxes and of chanting and laughing workmen; their bright purple headscarves fluttering in a breeze. Soil is shifted, rocks are moved. Basket after basket of debris is brought out of the trenches. As the dust of history is slowly removed, the ancient remains are rising gradually: Boulders, slabs, and walls pulled back into present-daylight. Slowly the earth is releasing those secrets of the past it was keeping for so many years. For centuries. For millennia.

And so business is going on. And on. The dusty work only interrupted by a short breakfast. Children from the nearby village are coming around, bringing their fathers and uncles and brothers some food and cool water. Everyone’s hungry – and more lively – by now, so this breakfast is a much more substantial and communicative matter than the sparse and mute one in the very morning: Over yet another tea (there’s always tea, get used to it), over some cheese and flatbread, over tomatoes and cucumbers and olives, conversations are drifting around the table for half an hour of otiosity. Half an hour of lethargic rest in the shadows; the sun – not shy at all anymore – now showing its true nature, relentlessly burning down from a shimmering sky. There’s no other shadow out there, so returning to work means returning into the heat of a furnace.

Breakfast. (Photo: T. Yildiz)

As dusty as busy. (Photo: J. Notroff)

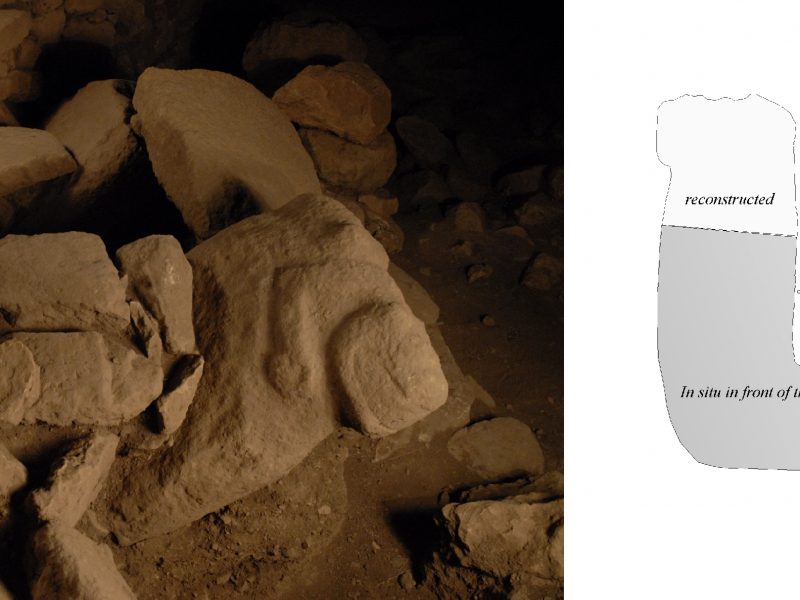

Back in the dust soon the clanking of picks loosening dirt and rubble can be heard. A group of visitors, marvelling at the site’s sight, takes the chance to curiously quiz the archaeologists before returning to their air-conditioned busses. Workmen continue to dig; students still are busily taking notes, picking out small pieces of charcoal and fragments of flint tools and stone vessels from the excavated soil, collecting them in buckets and plastic bags – each labelled with date and information on their exact find spot. Two workers are intently hauling a large sculpture to the edge of an excavation trench. Dirt is sifted dry and wet (a rather dusty respectively muddy business); a steady flow of find material is coming towards provisional lab and office facilities in the excavation’s ‘headquarters’ of construction containers and tents upon the next hill crest – eagerly awaited by specialists, keen to have a look onto the latest piece of obsidian or the peculiar amazing new stone sculpture.

“There’s help needed at the sieves.” (Drawing: J. Notroff)

While the sun is moving towards its zenith, work’s pace is decreasing noticeably. It’s an arduous business and after eight hours of digging, just when midday’s heat is reaching its peak, everyone is happy to call it a (field) day. Last measurements are taken and yelled and noted, last photos are taken too; tools and instruments, equipment and journals are collected and put away yet again. Bidding good bye, the crew of workmen is boarding tractors and trailers, leaving for that small village down the hill – dragging behind a dustcloud all the way. Buckets full of small finds are loaded into the mini bus and taken to the excavation house. As the bus is slowly crawling down the dirt track everyone’s trying to find a comfortable position, finally taking another short rest – legs stretched, the dusty hat pulled down over the eyes. With the madness of an average oriental big city’s rush hour the drive back costs a multiple of the time the way there in morning did took us – enough time for a nap also. Appreciated.

Daily commute. (Drawing: J. Notroff)

Back in town, as we leave the car and head through heated-up narrow old-town alleys towards the excavation house, buckets and pieces of equipment in hand, the muezzin is calling the faithful to prayer again. Well, for the archaeologists it’s lunchtime for now; the cook is already waiting. Of course a meal in the Orient is not finished without the mandatory tea (you get the idea), so showers still have to wait for yet another 10 minutes or so. There’s got to be time for that.

But even now work isn’t done yet for the day. After the refreshing effect of a shower (and fresh clothes; don’t you ever underestimate the effect of fresh clothes!), everyone’s gathering in the excavation house’s courtyard – again. The buckets brought back from site are emptied, the finds carefully cleaned and washed, sorted, and spread onto coarse screens to let them dry in the sun. Meanwhile those finds of the day before, now all clean and dry and pretty, are examined, sorted, listed, catalogued, drawn and photographed where necessary. Let alone the paperwork. Field notes and reports. Accounting and administration. More reports. Over are the times where an expedition to the middle of nowhere, far from home, office, and institute meant one wouldn’t be on call. In the age of globalization, mobile communication, and wifi even in the back of beyond, everyone’s expecting to receive an answer to e-mail, text, and phone call – preferably within the hour.

Afternoon shift at the dig house. (Photo: J. Notroff)

The darkness of night has already fallen (summer over here almost skipping the twilight of dusk), the muezzin has called the faithful to prayer one last time for today. Over dinner, some conversation and, finally!, a beer or glass of wine, another day’s slowly facing its end in the dim evening light of the excavation house’s courtyard. Sooner or later everyone’s pushing off; it’s not going to be a very long night – about 4.30 o’clock, ante meridiem, the muezzin will call the faithful to prayer again. And the archaeologists to finally get up. Again.

This short article was obviously inspired and fuelled by Agatha Christie Mallowan’s “Come, Tell Me How You Live” (the title of this contribution directly deriving from a poem in the short epilogue of her book). This ‘Archaeological Memoir’, published in 1946, gives an account of her days in the field together with her husband Max Mallowan (esteemed British archaeologist and excavator of Tell Brak, Tell Arpachiyah, and other sites) describing the daily routine of an archaeological excavation. It is a very entertaining, a witty and spirited little book; one I’d personally recommend not only to archaeologist-colleagues. Christie Mallowan (indeed identical to the well-known crime novelist you just may have thought of) slipped quite some of these archaeological adventures and experiences into her better known ‘Whodunnits’: “Murder on the Orient Express” (1934) and “Death on the Nile” (1937) evocating long and colourful journeys to these sites and “Murder in Mesopotamia” (1936) even depiciting an extraordinary dramatically case of ‘excavation fever’ – not at all unknown to those who can relate such a situation (minus the murder though, most likely).

Recent Comments