Recently a (peer-reviewed) paper published by M. Sweatman and D. Tsikritsis, two researchers of the University of Edinburgh’s School of Engineering, has made headlines, suggesting that the Göbekli Tepe enclosures actually were space observatories and that some of the reliefs depict a catastrophic cosmic event (the original publication in Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 17(1), 2017 is accessible online here [external link]).

A selection of the carved reliefs found on many of Göbekli Tepe’s T-shaped pillars is linked to and interpreted as depiction of actual stellar constellations. In particular Pillar 43, which is indeed an outstanding (but actually not exceptional) example of the site’s rich and complex iconography, is interpreted as record of a meteor shower and collision – with quite serious consequences for life on earth 13,000 – 12,000 years ago (this whole ‘Younger Dryas Impact’ hypothesis [external link] actually is disputed itself [external link], so making Göbekli Tepe a ‘smoking gun’ in this argument should absolutely ask for a closer look).

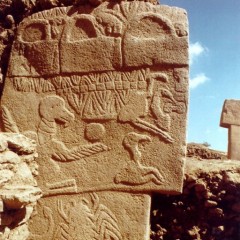

Pillar 43 in Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure D. (Photo: K. Schmidt, DAI)

Debate regarding a possible astronomic link and interpretation of the architecture and the characteristic pillars in particular are as old as the history of research regarding Göbekli Tepe, but as of yet no convincing proof for an actual celestial orientation or observation of such phenomena could have been put forward. We always were and still are open to consider these discussions. So, of course we were looking into the new study with quite some interest, too. After all it is a new and fascinating interpretation. However, upon closer inspection we as excavators of this important site would like to raise a few points which may challenge this interpretation in our point of view:

1. There still is quite a significant probability that the older circular enclosures of Göbekli Tepe’s Layer III actually were subterranean buildings – possibly even covered by roof constructions. This then somehow would limit their usability as actual observatories a bit.

2. Even if we assume that the night sky 12,000 years ago looked exactly like today’s, the question at hand would be whether a prehistoric hunter really would have put together the very same asterisms and constellations we recognise today (most of them going back to ancient Egyptian, Babylonian, and Greek scholars and descriptions)?

3. Contrary to the article’s premise the unearthed features at Göbekli Tepe are not shrouded in mystery. Published over the last years and decades, there is ample scientific literature available which unfortunately did not find its way into the study. The specific animals depicted in each enclosure’s iconography for instance seems to follow a certain intention, emphasizing different species in different enclosures. A purely substitutional interpretation ignores these more subtle but significant details. This also can be demonstrated for instance with the headless man on the shaft of Pillar 43, interpreted as symbol of death and mass extinction in the paper – however silently omitting the emphasised phallus in the same depiction which somehow contradicts the lifeless notion and implies a much more complex narrative behind these reliefs. There are even more reliefs on both narrow sides of P43 which went conpletely uncommented here.

4. It also seems a bit arbitrary to base this interpretation (and all its consequences as described in the paper) on what seems to be some randomly selected pillars and their iconography (the interpretation thus not covering “much of the symbolism of Göbekli Tepe” as stated in the paper, but merely the tip of that iceberg). In the meantime more than 60 monumental T-pillars could have been unearthed in the older Layer III – many of these showing similar reliefs of animals and abstract symbols, a few even as complex as Pillar 43 (like Pillar 56 or Pillar 66 in enclosure H, for example). And it does not end there: the same iconography is prominently known also from other find groups like stone vessels, shaft straighteners, and plaquettes – not only from Göbekli Tepe, but a variety of contemporary sites in the wider vicinity.

So, with all due respect for the work and effort the Edinburgh colleagues obviously put into their research and this publication, there still are – at least from our perspective as excavators of this important site – some points worth a detailed discussion. A more thorough exchange with the excavation team could have clarified many of these concerns.

Recent Comments