For many academics, images of scholars in front of bookshelves at home and group screenshots from video conferences are among the most common images of the corona pandemic. Thanks to a flexible IT structure and network-based access to digital data, the DAI was also well equipped to continue research and communication under suddenly changing conditions. Particularly in the IT-related fields of research, new dynamics can be observed, and the formats of academic exchange have also changed rapidly in a very short time. However, these possibilities find their limits when it comes to archaeological research in the field, such as excavations, surveys, building documentation, preservation of historical monuments or the study of finds in the depots of excavation houses and museums. Such activities have dominated our summer months so far and are part of the annual rhythm for many archaeologists.

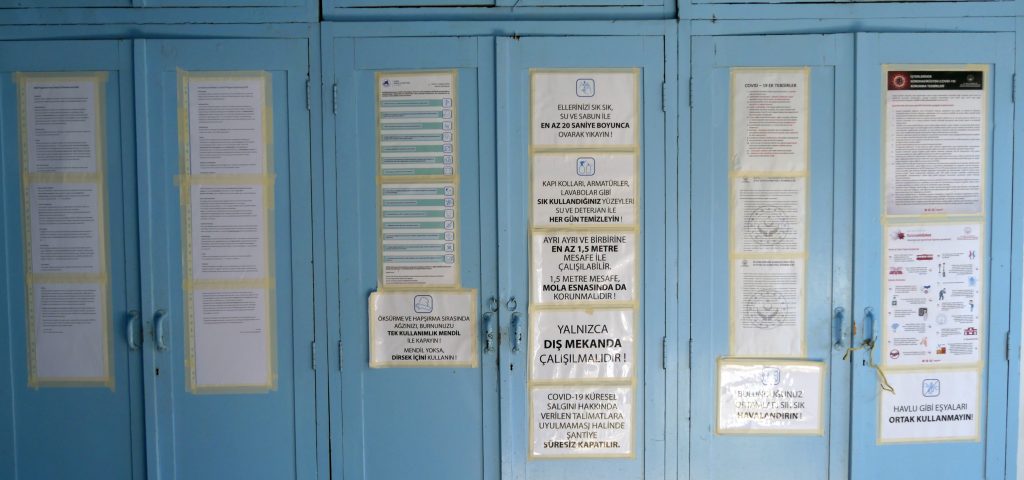

However, living and working together in excavation houses becomes a special challenge during the Corona pandemic. Since the health of the employees is always the top priority, it is crucial to implement a hygiene concept that effectively contributes to minimising risks, in addition to current information on the pandemic situation and a well-functioning health care system. For the Pergamon Excavation, this meant an extension of the campaign time coupled with a reduction in the number of staff, thus significantly reducing the density of people in the excavation house. In addition to common measures such as compulsory masks, distance rules, the general availability of disinfectants and the establishment of a one-way street system in the excavation house, sanitary facilities had to be rebuilt and equipped with new ventilation systems and alternative possibilities in case of quarantine had to be created (Fig. 1-4). In addition to the great discipline of all those involved, it is also thanks to these measures that the three-month campaign was carried out without any cases of disease.

2) Excavation house: toilets with new ventilation system and additional quarantine toilet (F. Pirson)

3) Fig-tree at the dining table with disinfectant (F. Pirson)

4) German-Turkish `signpostforest´ (F. Pirson)

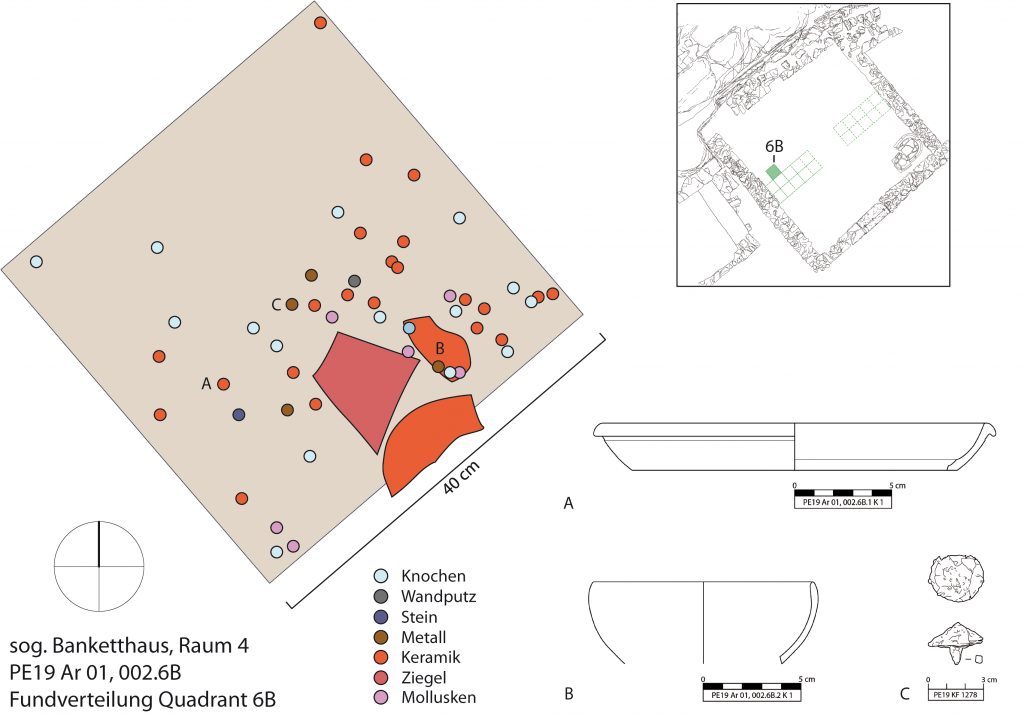

Fortunately, this year’s season in Pergamon was not only dominated by the pandemic, but also by a multitude of surprising discoveries and results, which at least partly compensated for the difficult conditions. To evaluate the micro-archaeological excavations of the previous year in the main room of the so-called “banquet house”, a system for flotating soil samples (Fig. 5) was put into operation. Initial analyses of the finds thus obtained show that fascinating insights into late Hellenistic banquet practice and the associated dietary habits are opening up (Fig. 6).

6) Mapping of the finds in a quadrant of the micro-archaeological excavation in the so-called banquet house (N. Neuenfeld)

For several years, the ancient funeral culture of Pergamon was one focus of our work, but at that time it was not possible to identify further Hellenistic graves and to investigate them using a modern spectrum of methods. In 2019, by chance, a previously unknown structure was discovered on the northern slope of the city hill, which we were able to excavate completely during this campaign. On a narrow terrace flanked by two circular buildings, a wealthy family buried their dead over several centuries (Fig. 7. 8). The location of the district below an ancient arterial road makes it an important example of the design of Hellenistic burial streets, which are among the leading forms of ancient burial sites, but which have not yet been documented in Pergamon.

8) Detail of the main Hellenistic burial: Pit in rocky ground with brick paving (J. Krasel)

Investigations in the surroundings of the suburban Asklepieion (TransPergMikro; read more) have also yielded new insights in the burial grounds. On the one hand, it is now possible to grasp the dimensions and forms of burials of an extensive necropolis that stretched around the sanctuary in the west of the ancient city. With the discovery of an inscription which apparently belonged to the grave of an augur who read the will of the gods from the behaviour of birds, we obtained a new individual testimony to the funeral culture of the Pergamenian elite during the Roman imperial period.

A main focus of this year’s surveys in the surrounding of Pergamon within the framework of TransPergMikro was the valley of the Geyikli northeast of Dikili, where rural settlement remains and traces of land use from the Bronze Age to the Ottoman era were detected. These include a newly discovered necropolis of burial mounds in the centre of a small settlement chamber (Fig. 9) and a natural sanctuary of the Kybele including a natural cave. Special attention was paid to a Roman thermal bath complex (Fig. 10), some of which has been preserved as visible ruins and whose extention appears to be much larger than previously assumed. In addition to the well-known ‘health resort’ Allianoi east of Pergamon and the so-called Cleopatra Hamamı just outside of the city, there was apparently also an elaborate spa in the west of the Micro-region, which contributed to the wellness of the inhabitants of the Pergamon Micro-region in the Roman imperial age.

10) Ruins of the Roman imperial thermal bath in Geyikli Dere (B. Ludwig)

Pottery production was an important branch of economic life in the Pergamenian landscape, the study of which is one focus of TransPergMikro. The investigation of the ancient potteries of Pitane (Çandarlı), whose fieldwork was completed in PE 20 (read more), promises new insights into the chronology, organisation and extent of a production that contributed to regional supply and at the same time was integrated into supra-regional distribution networks.

A further project, which is dedicated to the urban economic areas of the Pergamenian Micro-region, was able to reconstruct the development of production and distribution in the area of the city excavation (Fig. 11). Also within this project, mills and millstones have been compared as important guiding fossils of food production (Fig. 12).

12) So-called Olynthian mill of andesite (S. Völkel)

Another core question of TransPerMikro concerns the nature and extent of a large building programme with which the urban appearance of Pergamon was fundamentally changed in the 2nd century AD at the latest. With the amphitheatre and the neighbouring Roman theatre (Fig. 13), two key monuments of the presumed programme were further investigated in this campaign using the methods of archaeological building research (Fig. 14). The study of the amphitheatre, which is planned for three campaigns, focused on evidence for the graphic reconstruction of the missing parts and on damage mapping of the standing structures (Fig. 15). The reconstruction of the original appearance of the building is an essential prerequisite for the analysis of economic aspects of construction, including those on resource consumption, which results in interfaces with the work of archaeology and physical geography within TransPergMikro.

14) Use of a drone with spotlight to document vaults in the amphitheatre (A. Tuğlu)

15) Damage mapping in the amphitheatre (G. Günay)

The international team of geographers has investigated, among other things, the natural environment of a newly discovered ancient building east of Bergama, which is embedded in the alluvial deposits of the Kaikos (Bakır Çay) and its tributaries (read more). In the future, this finding could provide a new basis for the evaluation of natural disasters as factors in the transformation of the settlement structure in the Pergamenian Micro-region.

These and many other topics were discussed on November 7th 2020 at the second “Werkstattgespräch” of TransPergMikro with over 35 participants in a video conference (see programme). The event served for the first interdisciplinary exchange of results obtained during this year’s work campaign and the analysis of sample material from 2019.

The short and thus incomplete overview of the manifold activities within the framework of the DAI-Pergamongrabung and TransPergMikro should conclude with our activities in the field of preservation of architectural monuments and cultural heritage protection. A real milestone was reached with the completion of the many years of work to restore and present the Red Hall of Pergamon (Fig. 16) (read more). The restoration of a 19th century shop house in the old town of Bergama (Fig. 17. Funding from the Gerda Henkel Foundation) is intended to create a new place for the residents of the former Greek quarter below the excavation house to meet and to exchange with the touristic visitors. We hope to celebrate the opening after the end of the pandemic with a local neighbourhood festival.

17) Bergama, Talatpaşa Mahallesi. Restored historical shop-house as future communal centre (İ. Keskiner)

Our special thanks go to all participants of this year’s campaign for their great commitment and sense of responsibility. We would like to thank the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Turkey for approving our work and the three government representatives for their collegial support. The same applies to the management of the Bergama Museum and the Bergama City Council. Last but not least we would like to thank the various sponsors of the Pergamon Excavation, without whose generosity and trust our work would not be possible.