Recently a colleague from the University of Gothenburg, Bettina Schulz Paulsson, published a most interesting study [external link] about the origin and evolution of megalithic constructions in Europe (Schulz Paulsson 2019). Since we received quite a number of questions and comments about the absence of any reference to the Göbekli Tepe monuments in the discussion, we thought this could be a good opportunity to address a wider misunderstanding regarding megalithic phenomenona throughout the world: It is important to note that there is no one globe-spanning ‘Megalithic Culture’, but rather megalithic cultures (plural) – building with great (Greek: mégas) stone (Greek: líthos).

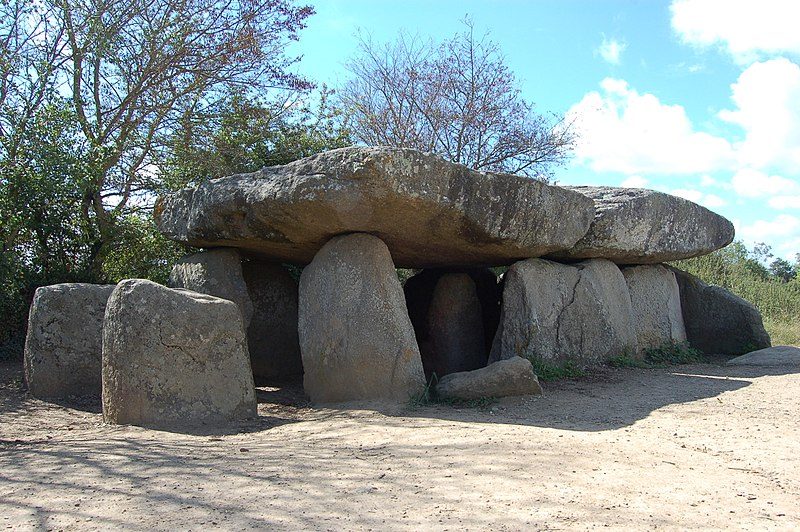

Dolmen de la Frébouchère, France. (Photo: Wladyslaw, Creative Commons: CC-BY-SA 3.0).

In her analysis, Schulz Paulsson looked into the origin of a very specific type of European Neolithic monuments known from the Atlantic coast up to Scandinavia: So-called dolmens, which are basically built of large stone slabs, piled on top of each other, much resembling giant tables. These monuments were erected above ground and most often covered by a mound of stones or soil. Archaeological research could demonstrate that these can be considered megalithic tombs (e.g. i.a. Montelius 1907; Joussaume 1985; Sherrat 1990; Cummings and Richards 2014). The current study could demonstrate, based on more than 2,400 radiocarbon dates from such megalithic constructions and their surroundings and Bayesian modelling (cf. e.g. Bronk Ramsey 2009), that the first megalithic tombs of this type seem to date about 4,800 BC in the Channel Islands, Corsica, Sardinia – and north-western France. But only in the latter region there are also known similar earthen grave monuments actually preceding the first megaliths. Since the other regions are lacking any similar related earlier structures, the possible origin of this specific building tradition apparently thus could be tracked back to the Paris basin (if this really means megalithic building tradition in Europe is necessarily the result of cultural diffusion may be worth a discussion of its own; in an earlier comment, University College London’s David Wengrow noted the interesting possibility of similar underlying principles and related skills in maritime techniques (dragging and lifting canoes) and megalith transport [external link]).

Göbekli Tepe, Building D. (Photo: N. Becker, DAI)

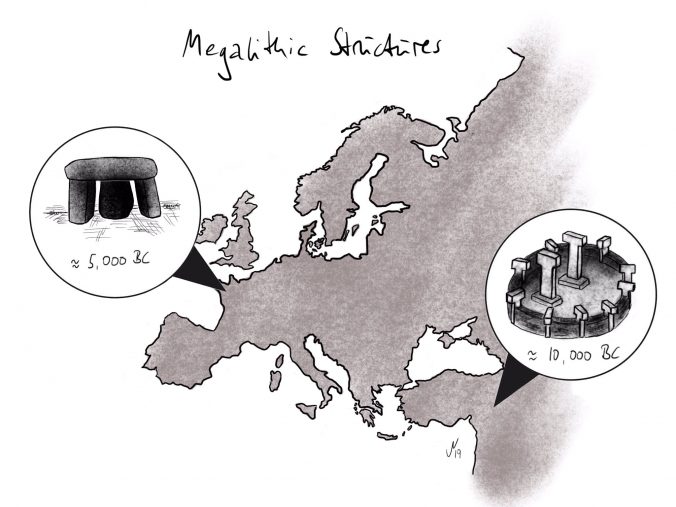

But what about Göbekli Tepe now? First of all, the monumental structures excavated in south-eastern Turkey are significantly older (dating to the 10th millennium BC) – and also significantly different from the European megalithic tombs discussed in Schulz Paulsson’s study. Although a relation to mortuary ritual may be discussed for activities having taken place at Göbekli Tepe as well (cf. Notroff et al. 2016; Gresky et al. 2017), according current state of research these buildings were not primarily constructed as graves (to this day no related burials were found), but as place of complex social gatherings, exchange and communication. Unlike the European dolmens, Göbekli Tepe’s monuments consist of monolithic T-shaped pillars arranged in considerably larger circles, grouping around another pair of similar pillars. Dry-stone walls and stone benches are connecting these pillars, forming the characteristic huge circular structures.

So, to cut a long discussion short: While there is a clear typological, regional, and chronological relation between several of the European megalithic constructions, no link whatsoever leads to (or from) the Pre-Pottery Neolithic monuments in Anatolia. These are very different structures of a very different construction type and a very different function. From different periods and geographical regions, thousands of kilometres and years apart. There are no intermediate forms bridging this huge gap, no other finds suggesting any such relation.

References:

Chr. Bronk Ramsey, Bayesian Analysis of Radiocarbon Dates, Radiocarbon 51(1), 2009, 337-360. [external link]

V. Cummings and C. Richards, The essence of the dolmen: the Architecture of megalithic construction / Préhistoires Méditerranéennes [En ligne], Colloque |2014, mis en ligne le 25 novembre 2014, consulté le 05 mars 2019 [external link].

J. Gresky, J. Haelm, L. Clare, Modified human crania from Göbekli Tepe provide evidence for a new form of Neolithic skull cult, Science Advances 3(6), 2017, e1700564. [external link]

R. Joussaume, Des dolmens pour les morts, Paris 1985.

O. Montelius, Dolmens en France et en Suède, Le Mans 1907.

J. Notroff, O. Dietrich, K. Schmidt, Gathering of the Dead? The Early Neolithic sanctuaries of Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey, in: C. Renfrew, M. J. Boyd and Iain Morley (eds.), Death Rituals, Social Order and the Archaeology of Immortality in the Ancient World. “Death Shall Have no Dominion”, Cambridge 2016, 65-81.

A. Sherratt, The genesis of megaliths: Monumentality, ethnicity and social complexity in Neolithic north-west Europe, World Archaeology 22, 1990,147-167. [external link]

B. Schulz Paulsson, Radiocarbon dates and Bayesian modeling support maritime diffusion model for megaliths in Europe, PNAS 116(9), 2019, 3460-3465. [external link]

In short, using stone for monumental purposes requires no pre-history : stone is an expression of solidity and permanence still, and indeed was the only one available to people who were restricted to natural materials. Declaring that its presence in archaeological sites is proof of cultural links over huge gaps in time and space lacks scientific objectivity. When imagination takes precedence over known facts we leave science enter the realm of science fiction.

I didn’t read the paper. Did it mention the Anatolian migration/invasion into Europe following the 8.2 kiloyear event? This is known from DNA evidence – hard scientific facts. The timing is rather suggestive. In any case, given that we now know of a widespread interest in astronomy, including precession of the equinoxes using the same constellations as today, since 40,000 years ago (see my paper on Palaeolithic art) across Europe (at least), it’s clear the links go much further back in time than these authors are prepared to consider. Also consider Witzel’s ‘The origins of the world’s mythologies’. He makes the same suggestion, that the mythologies of the world (outside Africa and Oceania) are all connected and go back at least 40,000 years. I agree, that while the connections to later European dolmens are hard to prove, it is not fanciful to propose a connection. See my book ‘Prehistory Decoded’ for a serious scientific case, and why 40,000 years, or so, is the timescale in question.

Suggestive is not evidence though, I’m afraid. And I think we agree to disagree on far-reaching connections posed by an interest in astronomy. While I wouldn’t even deny such interest (after all that kind of curiosity is essentially what makes us human), I still don’t think there’s enough evidence to construct a communication-network or diffusion of the scale implied by such longue durée connections. But you know that I’m more on the sceptical side regarding this.

Connecting the migration of Anatolian farmers into Europe with the megalithic tradition of western Europe would seem plausible, except the archaeological record does not support it. No point building a theory that ignores the wider picture. The Gubekli Tepe style construction disappeared well before the migration and showed no similarity to the megalithic tomb structures anyway.

Absolutely agree, with current evidence. Nevertheless, science begins with questions, not answers. The ‘no point’ view is narrow. It’s a valid question to investigate. Especially given that my work demonstrates, scientifically, an ancient system of astronomy, recorded with animal symbols, possibly going back as much as 40000 years, with examples from western Europe through to Ancient Egypt. If you think this sounds implausible, you should read my book Prehistory Decoded. I think you’ll find it enlightening. Given this scientific context, it seems to me to be very plausible that all these megalithic structures are linked by a very ancient astronomical system. Proving it is another matter, of course, but asking the question is entirely reasonable. Jens doesn’t like my scientific findings, unfortunately. But you can’t pick and choose. Live by the sword, die by the sword.

It’s actually not so much question of ‘liking’, but finding the proposed line of arguments convincing. Or not. Anyway, I appreciate any input and won’t dodge a serious discussion of reliable archaeological context.

I would, however, kindly ask you not to turn the comments section here into an advertising rostrum, assuming the title of your book already came through in the previous comment …

But simply re-stating your argument without addressing the lack of solid archaeological to support a link between the features and purpose of the Gubekli Tepe type of megalithic monument and the much younger western European tombs is indeed without point. Nothing wrong with picking and choosing if the evidence is unconvincing.

It’s not a gigantic paper. It doesn’t really cover anything before about 5ka BP, just diffusion of ideas amongst settled peoples. There’s an unstated model in there that humans were essentially everywhere and there was nowhere “new” to go ; instead ideas move around – ideas of more efficient food production, of societies that work less individualistically and so produce more offspring, etc.

Dear Jens,

while I certainly agree with you on the disconnectedness of Göbekli Tepe and European megalithic culture(s), one thing that’s been most puzzling to me is that I keep stumbling upon reference to neolithic structures of “complex social gatherings, exchange and communication” being deliberately burried or dismantled. One example I’ve been able to dig up quickly just now is the structures at the Ness of Brodgar. See for example the report https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2014/08/neolithic-orkney/ or more detailed at http://www.nessofbrodgar.co.uk

There apparently is evidence of a huge final (?) feast involving some hundreds of cattle too, if I remember correctly.

The time span between the use of these structures and of Göbekli Tepe is immense, yet, while highly speculative, it seems very odd that these people seem to have felt the need or compulsion or indeptedness to tradition to bury their structures.

Cheers,

Claas

Actually, dismantling, destroying, and / or burying structures not in use any longer is not an exception in the course of human history, but happened more often than not (be it to prevent any misuse or profanation of formerly important places or the simple fact to leave no trace). Your example of the Ness of Brodgar is really fascinating and actually seems to prove this kind of interpretation.

Perhaps, Jens. Nevertheless, one can’t help speculating that burying these structures is actually a form of respectful regard for their utility, function, religious or spiritual value. Burying them could be a way of preserving, in a way, the time(s), i.e. eras, that these structures served people. It is a way of demonstrating continuing respect for those times that have now passed, the people that lived then, and effort preserve it all-and I mean, all- for posterity. However, burying them also seems to suggest the need for people to “move on” into the future, past the “need” for such structural symbols or statements.

Some of these sites were buried intact, indicating the burials were supposed to actually preserve “history.” And, possibly, since some are relatively intact, to preserve “history” exactly. I choose to believe that these generations of builders not only worshiped ancestors, they also “worshipped” descendents, or the promise of eventual descendents in future generations. They believed in the future and that, like the lyrics in a song, “There is a time to live…there is a time to die” , a time for this and a time for that. And, then, at the proper “time,” a time to let go.

Thank you Jens. Spot-on. Could not say it better..

Anything about the Dolmens of Russia and Georgia in that study?