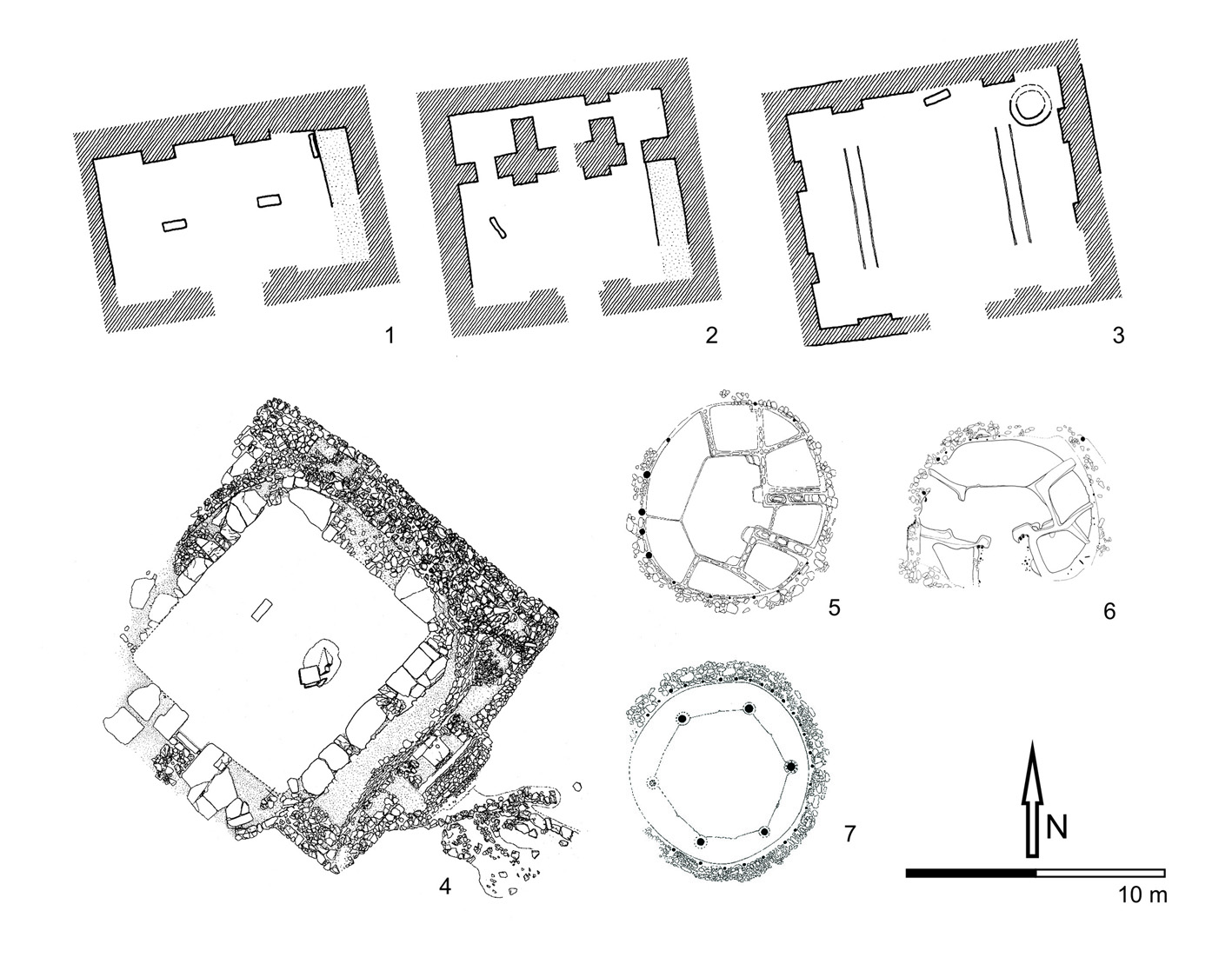

The detailed and complex, often supposedly even narrative reliefs at Göbekli Tepe’s T-pillars are one of the most fascinating features of the site (next to its impressing monumentality of course). The crucial question of its interpretation is well related to our understanding of the iconography and what it meant in its creators’ world view. Do the respective animals represent certain segments within Pre-Pottery Neolithic hunter communities, are they depicting actual events or do they give a more mythological account of spiritual concepts?

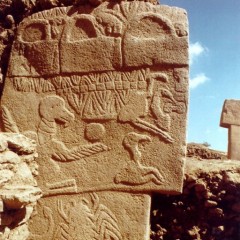

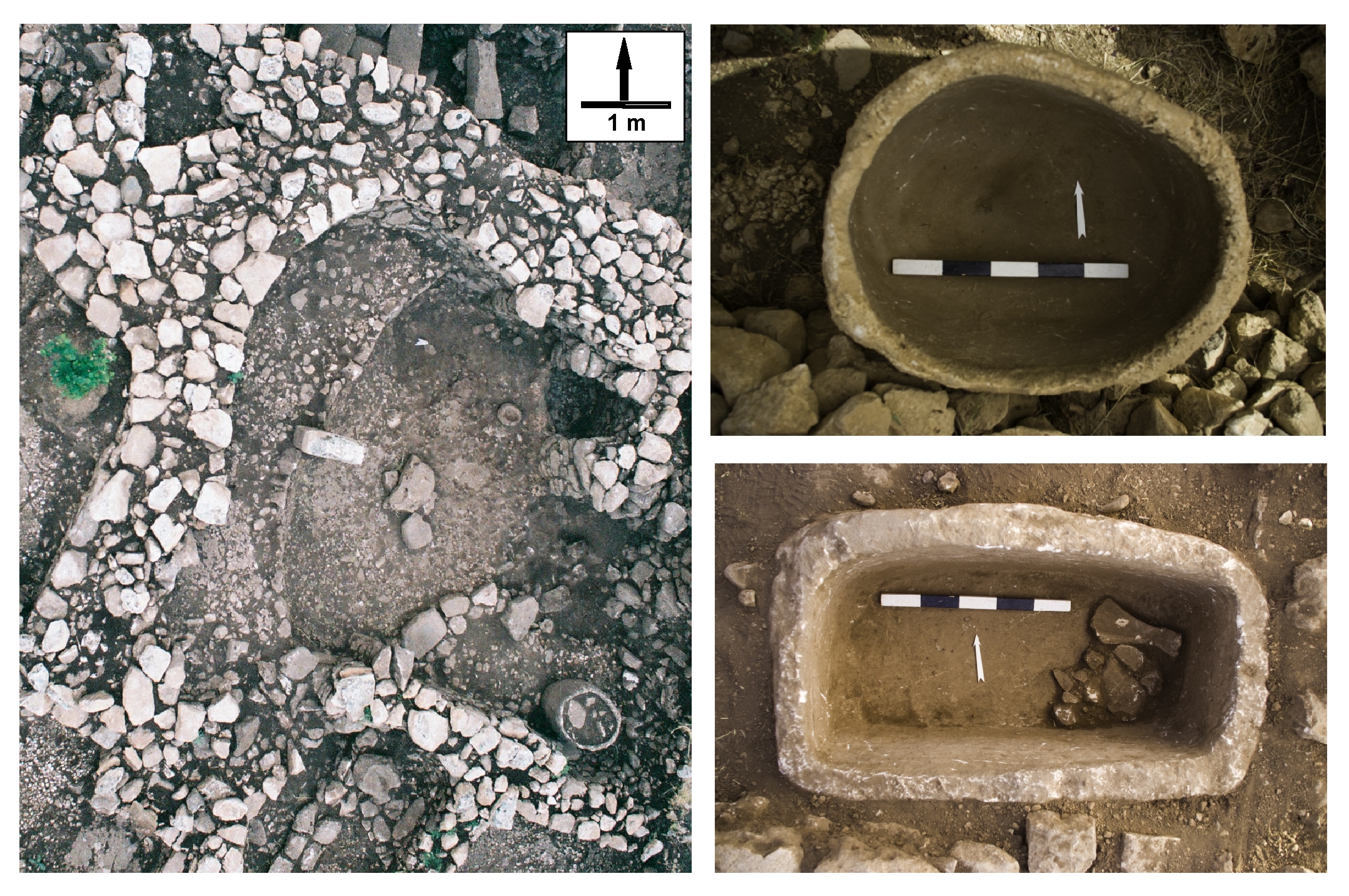

Among the skilful naturalistic reliefs, predominantly depicting animals in an accuracy that bears witness of a close relation to and careful observation of nature, birds seem to take on a special role. Water birds like ducks and cranes, but also storks, ibises, and vultures are a recurring motif in this stone-age picture book. In particular because of this careful and dedicated naturalistic representation of the animals depicted, an image on Pillar 2, one of the earliest discovered T-pillars at Göbekli Tepe, was puzzling from the very beginning (Schmidt 2012, 116-119). There, underneath an aurochs and a fox, a crane was carved into the limestone (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Pillar 2, Göbekli Tepe. Showing reliefs of aurochs, fox, and crane. The latter one with an extraordinary, rather not brid-like leg-anatomy. (Photo: K. Schmidt, DAI)

Again, one can only admire the virtuosity of this work, clear outlines forming the animals in the typical flat relief style well attested at the site from other carvings already. Yet something about that crane looks incongruous. Its long legs seem a bit odd, resembling much more those of a human than what would be expected as typical for a bird. Upon closer inspection a bird’s legs appear to bend backwards – so quite the opposite of what is depicted here. Actually, and we have to emphasise this here for any (archaeo-)zoologist’s peace of mind, this is only half true since bird-knees are situated much closer to their pelvis inside the body and not visible outside; what often is (erroneously) mistaken for the knees are in reality their tarsal (ankle) bones. However, the depiction of that crane on Pillar 2 still looks off from what could be seen in nature – so, would this mean rather poor observation skills or a lazy craftsman in this case? Since other reliefs from the site do properly depict bird anatomy (cf. Fig. 2), ignorant artists do not seem to be the most convincing explanation. Should we thus consider some intentional deviation from the naturalistic mode of representation which dominates the majority of Göbekli Tepe’s iconography here? If so, what could this peculiar depiction mean?

Fig. 2: Pillar 56 from Göbekli Tepe, however, does show (among many other animals) the depiction of long-legged birds with proper anatomical legs. (Photo: N. Becker, DAI)

In 2003 Nerissa Russell and Kevin J. McGowan published a most fascinating paper [external link] about a notable crane-bone find from Pre-Pottery Neolithic Çatalhöyük (Russell & McGowan 2003). This central Anatolian settlement site dates to the middle of the 8th and the 7th millennium BC (PPN B to Pottery Neolithic) and shows some considerable links with Göbekli Tepe, especially in terms of iconography. The find of particular interest here is a single Common Crane left-wing coming from a deposition at Çatalhöyük’s East Mound. These bones were found together with a cattle horn core, two wild goat horns, a dog head, and a stone mace head. This association of cattle, canid, and crane alone already may be a noteworthy correlation to the depiction on Pillar 2 from Göbekli Tepe. Yet the analysis of the crane bone itself is even more interesting: it is the part of the wing which has little flesh, but the large flight feathers attached. Consequently, the cut marks on these bones do not indicate simple butchery waste, but the intention to separate the wing at the joints. Furthermore, the cutting motions indicate that apparently one or two holes were pierced through the skin between the bones. While one could of course imagine that the wing could have been mounted to a lot of things, the authors plausibly suggest that it might have been part of a costume – fibres running through the holes attested by cut marks could have been helped to attach it to a person’s shoulder for instance (Russell & McGowan 2003, 447-448).

One of the most intriguing facets in this context is that cranes are famous for their dances. Breeding pairs and whole groups of cranes perform these complex movements. Their dances serve purposes of socialisation and pair bonding, but also to avert aggression. As soon as one of the birds starts, others are joining – yes, they even would do so if a human initiated the dance. Dancing was emphasized as integral social behaviour among PPN hunter groups, stressing communal unity and intensifying group cohesion (Garfinkel 1998). Bipedal and almost human-sized, with a comparable life-span and similar social structure, it is easily imaginable that these hunters somehow could identify with the dancing cranes, maybe even consider them reborn humans or ancestors. Russel and McGowan thus suggest that crane dances may well have been imitated to re-enact myths of origin, maybe of the own clan or humanity as such (Russell & McGowan 2003, 451-453) (Fig. 3). Related ritual dances are indeed not unknown from historic and ethnographic contexts and have been attested from a wide geographical and chronological range. Examples are known among Khanty (Ostiak) shamans from Siberia (Armstrong 1943, 73; Balzer 1996), the indigenous Ainu of Japan (St. John 1873), the Twa of central Africa (Campbell 1914, 79), and the sema dances of the Alevi in Turkey (Erol 2010) to just name a few.

Fig. 3: Dancing the crane dance. (Drawing: J. G. Swogger, with courtesy of the Catalhöyük Research Project)

So, since the fascination with cranes and their dances seem to be a thoroughly human phenomenon throughout space and time, the possibility of related Neolithic rituals should not come as a surprise. Cranes seem to have played an important role in the world of PPN hunter-gatherers. Remains of crane bones were reported from PPN B Jericho (Tchernov 1993) and Çatalhöyük (Russel & McGowan 2005) for instance, and they are known in significant numbers from Göbekli Tepe as well (where they form the second largest group in the avifauna right after corvids (cf. Peters et al. 2005, Table 1)). Next to the already introduced crane depiction from Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 2, similar reliefs were discovered on Pillars 33 and 38 which, too, stand out due to their comparatively thick legs and what seems to be ‘human-like knees’ (Fig. 4 and 5). From PPN B Bouqras in Syria a frieze of about 18 painted and incised cranes is known – the repeated depiction of the same posture maybe indicating a dancing scene (Clason 1989/90; Russell & McGowan 2003, 450). Another little known painting at Çatalhöyük displays two cranes facing each other, their heads raised (Mellaart 1966, 190, Plates LXII-LXIII; Russell & McGowan 2003, 450). Since noticeably often pairs of animals facing each other are depicted, cranes may have been linked to a larger symbolism of pairs or twins which well reminds of Göbekli Tepe’s dualistic central pillars as well.

Fig. 4: Of the three birds depicted on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 38 at least two (likely to be identified as cranes) demonstrate rather unusually bend, almost human-like legs. (Photo: K. Schmidt, DAI)

Fig. 5: Detail of Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 33 showing a crane (note the characteristic neck, head, and tail feathers) with unusual sturdy and bend legs. (Photo: K. Schmidt, DAI)

The conspicuousness of the Göbekli Tepe crane depictions, which, since large birds are practically unknown from the older, Palaeolithic pictorial art, might be the oldest yet known images of this bird, was already noted upon their discovery by Klaus Schmidt (Peters et al. 2005, 227; Schmidt 2003, 26-28; 2012, 170-174, 182-184). The representation of human legs somehow evoke the impression of masked people (which would not be surprising, given the discovery of several stone masks at Göbekli Tepe) yet leave us with the still rather bird-like depiction of three (or four) ‘toes’. Schmidt suggested to not just identify this as simple masquerade but, on the basis of ethnographic analogies regarding shamanistic rituals of hunter communities, maybe even as the visualisation of a transformation into the animal itself (Peters et al. 2005, 231; Schmidt 2012, 119, 205-208). A kind of cognitive, and subsequently accepted physical metamorphosis in the course of the ritual by imitating the cranes’ dancing. Although proper evidence for such specific rituals and performances naturally is rare in the archaeological material, this line of thought at least offers an interesting interpretation for the unusual deviation from the strictly naturalistic animal depictions. Furthermore, together with the possible remains of what seems to be a crane costume from Çatalhöyük, it adds a fascinating facet to our slowly growing understanding of Pre-Pottery Neolithic social and ritual life.

It seems intriguing to even expand these thoughts beyond the discussion of dancing humans disguised as cranes. One of the wall paintings from Çatalhöyük for instance may also show vultures with human legs according to James Mellaart (Mellaart 1967, 167, Figs. 14 & 15). And at the foot of one of Enclosure D’s central pillars at Göbekli Tepe, right underneath the depicition of a fox skin-loincloth that pillar was ‘wearing’, the bones of a foxtail were found – probably hinting at the presence of a real such item of clothing there. Thus it seems reasonable and necessary to also consider other, even more costumes and their possible application in PPN ritual. As Russell and McGowan already emphasized (2003, 454): bulls (and vultures) are not the only animal symbols in the Neolithic world and we have to keep our eyes open to identify the more fragile clues among the material remains we are studying.

References (incl. further reading)

E. A. Armstrong, Crane dance in East and West, Antiquity 17, 1943, 71-76.

M. M. Balzer, Flights of the sacred: Symbolism and theory in Siberian shamanism, American Anthropologist 98 (2), 1996, 305-318. [external link]

D. Campbell, A few notes on Butwa: An African secret society, Man 14, 1914, 76-81.

A. T. Clason, The Bouqras bird frieze, Anatolica 16, 1989/90, 209-213.

A. Erol, Re-Imagining Identity: The Transformation of the Alevi Semah, Middle Eastern Studies 46:3, 2010, 375-387. [external link]

Y. Garfinkel, Dancing at the Dawn of Agriculture. Austin: University of Texas Press 2003.

J. Mellaart, Excavations at Çatal Hüyük, 1965: Fourth preliminary report, Anatolian Studies 16, 1966, 165-191.

J. Mellaart, Çatal Hüyük: A Neolithic Town in Anatolia. London: Thames & Hudson 1967.

J. Peters, A. von den Driesch, N. Pöllath, K. Schmidt, Birds in the megalithic art of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, Southeast Turkey. In: G. Grupe and J. Peters (eds.), Feathers, Grit and Symbolism. Birds and Humans in the Ancient Old and New Worlds. Proceedings of the 5th Meeting of the ICAZ Bird Working Group in Munich (26,7.-28.7.2004). Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH 2005, 223-234.

N. Russel and K. J. McGowan, Dance of the Cranes: Crane symbolism at Çatalhöyük and beyond, Antiquity 77, 2003, 445-455. [external link]

N. Russel and K. J. McGowan, Çatalhöyük bird bones. In: I. Hodder (ed.), Inhabiting Çatalhöyük: Reports from the 1995-1999 Seasons. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 99-110. [external link]

K. Schmidt, “Kraniche am See”. Bilder und Zeichen vom frühneolithischen Göbekli Tepe (Südosttürkei). In: W. Seipel (ed.), Der Turmbau zu Babel. Ursprung und Vielfalt von Sprache und Schrift. Band IIIa: Schrift. Wien – Milano: Kunsthistorische Musuem Wien 2003, 23-29.

K. Schmidt, Göbekli Tepe. A Stone Age Sanctuary in south-eatern Anatolia. Berlin: ex Oriente e.V. 2012.

H. C. St. John, The Ainos: Aborigines of Yeso, Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 2, 1873, 248-254.

E. Tchernov, Exploitation of birds during the Natufian and early Neolithic of the southern Levant, Archaeofauna 2, 1993, 121-143

Recent Comments