The reason I haven’t posted so much in the last months was because the start of the project „Plant Food Management at Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe“ was requesting a lot of preparations, which left me with few time for blog contributions (I’m tweeting my research step by step, though, under: @laura_dtrich).

The main aims of my research project is to reconstruct the use of plants in the food spectrum at Göbekli Tepe, the plant management strategies and the interaction between man and environment on one side, and to contribute to an explanation for the special character of the site through new insights from this point of view on the other side. The study of plant resources and plant food at Göbekli Tepe is of great importance to understand Early Neolithic subsistence in the Levant and, linked to this, economic, social and biological processes that shaped our modern world. The site covers a long time span, in which the Neolithisation, i.e. the domestication of plants and animals, took place, until a point of no return to the world of hunters and gatherers was reached.

Göbekli Tepe is a special site, most probably a central site for meetings, and a cultic place with monumental architecture. It is not likely, at the current state of research, to interpret the site as a settlement (at least not as a “classic” settlement with populations living permanently at the site). But the more or less permanent presence of groups of people, erecting monumental architecture and/or maintaining it has to be assumed, and their subsistence was most likely an important issue. Also, social events like feasting could have played an important role at the site (Dietrich et al. 2012: O. Dietrich, M. Heun, J. Notroff, K. Schmidt, M. Zarnkow, The role of cult and feasting in the emergence of Neolithic communities. New evidence from Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey. Antiquity 86, 2012, 674-695).

Plants seem to be a more stable food resource compared to the partly migratory hunted animals, and the presence of an impressive quantity of storage vessels is certainly a hint for the massive storage of plant food at Göbekli Tepe. Different approaches for a reconstruction environments and plant use exist, for example through pollen and phytolith analysis. These methods can be theoretically used, but still have some methodological problems to be solved. The reconstruction of plant food is largely based on the botanical analysis of the plants discovered at a site (in significant contexts). But objects like grinding stones can make a significant contribution to our knowledge on plant use. Macrobotanical analysis has shown the use of einkorn, emmer, barley, pistachio and almonds at Göbekli Tepe (Neef 2003: R. Neef, Overlooking the Steppe-Forest: A Preliminary Report on the Botanical Remains from Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe (Southeastern Turkey). Neolithics 2, 2003, 13-16). However, there are only very few plant remains from Göbekli Tepe, and they are also badly preserved. The bad preservation conditions for such remains will inevitably lead to a very biased image regarding plant food at the site.

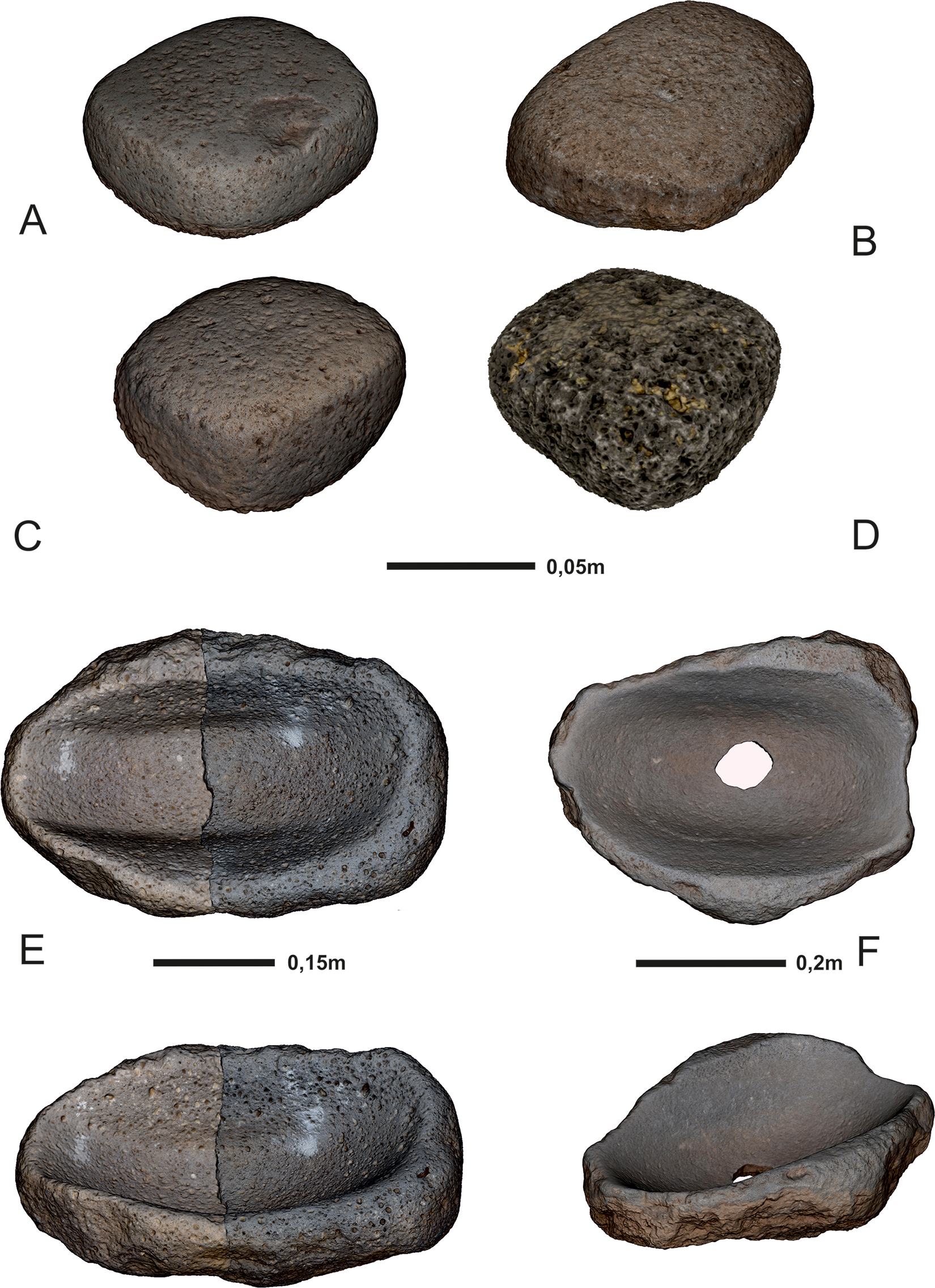

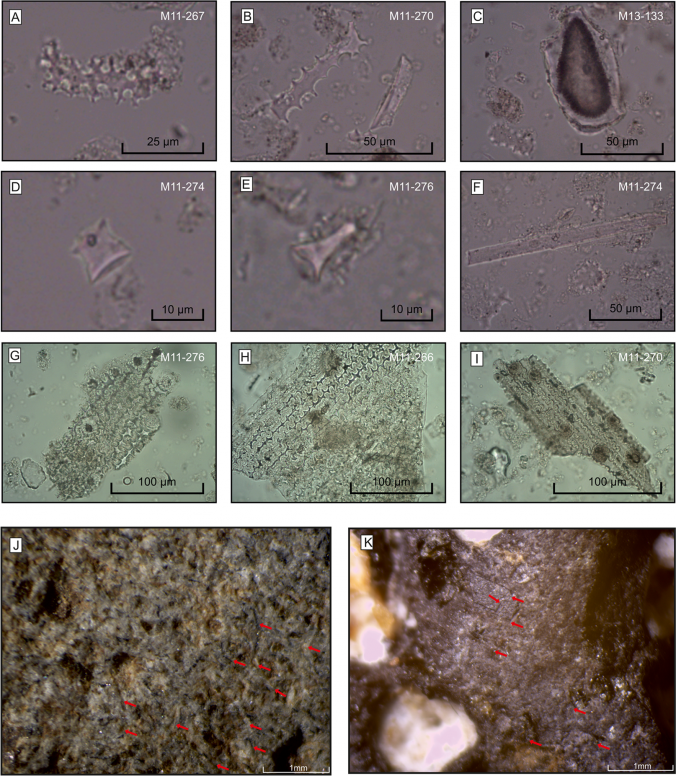

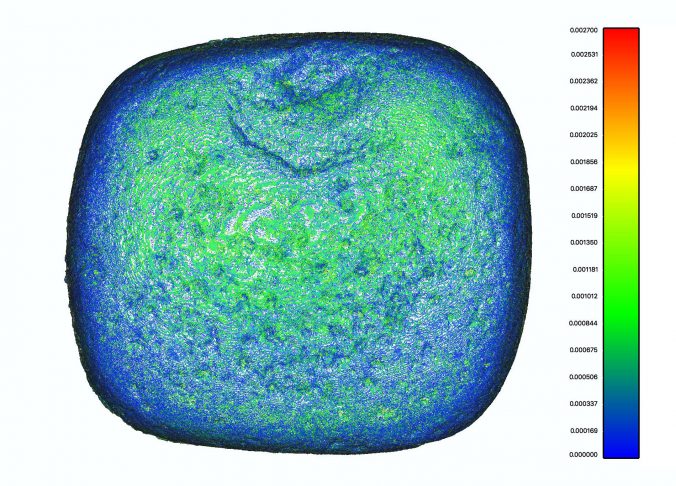

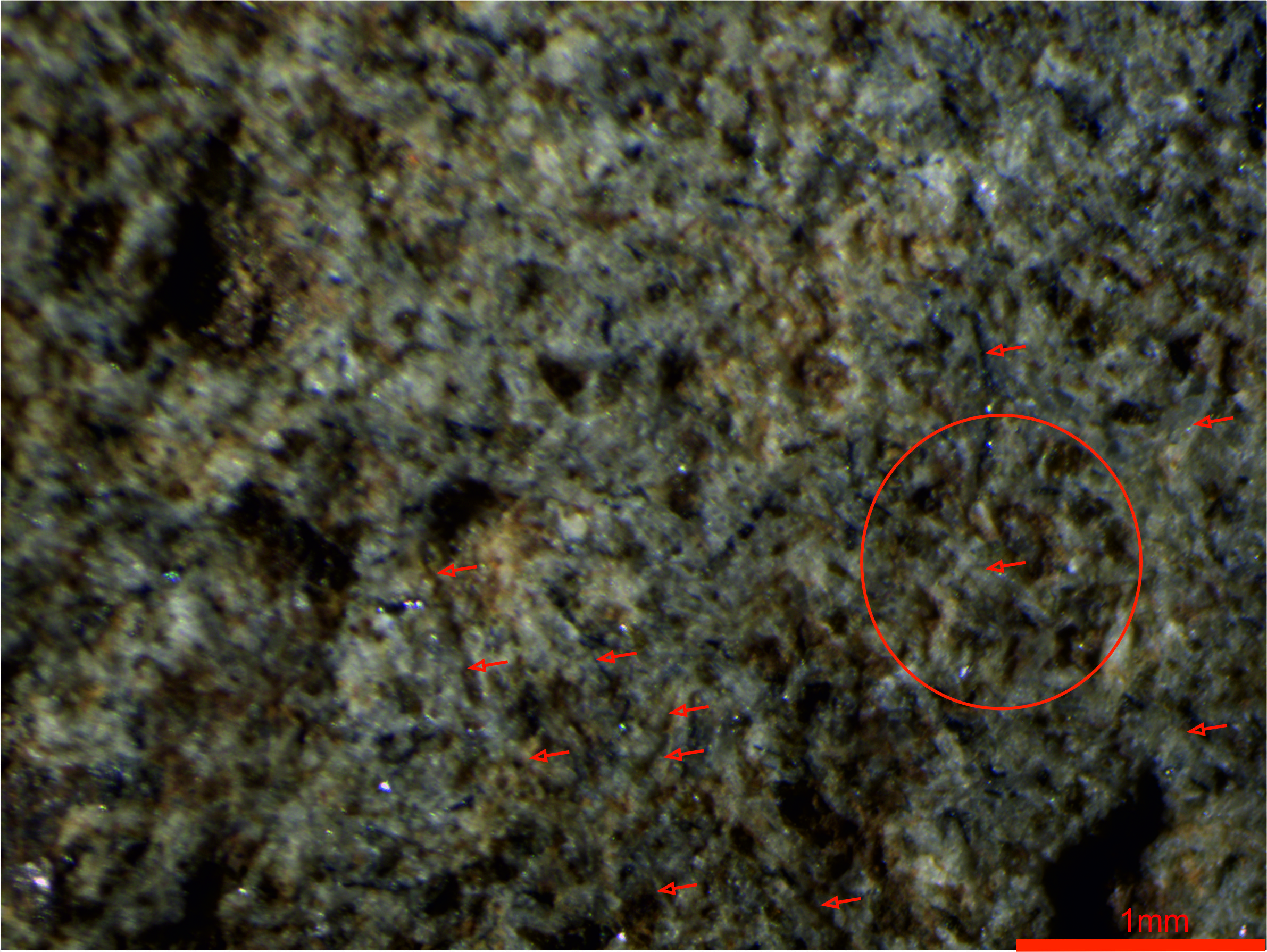

Given this situation, objects for the preparation and storage of food are a much more objective method to quantify the actual use of plant resources. There are over 10.000 grinding stones from the site. It is known from ethnographically sources that grinding stones were used for processing numerous foodstuffs (cereals, nuts, legumes, herbs, even meat, cheese or grasshoppers) but also minerals (salt, ochre), sugar and even animal skins. The processing of meat, ochre and animal skins was observed in several Epipalaeolithic sites in the Levant (Dubreuil et al 2015: L. Dubreuil, D. Savage, S. Delgado, H. Plisson, B. Stephenson, I de la Torre, Use-wear analysis of ground stone tools: discussing our current framework, in J. Marreiros, J. Bicho (Eds.) Use-wear handbook 105–158. Berlin, Springer 2015). One of the main aims of analyzing grinding stones is to deduce exactly their functions, and that can be done by analyzing their surface with the microscope for usewear; 3 D models are also useful tools for quantifications of use. Grinding different materials will produce different wear on the surface. The specific patterns of usewear traces can be compared with experimental objects (blog contribution coming up), used for grinding just one material. This is one of the best and most exact ways to deduce the function of grindings stones and, through statistically and stratigraphically secured observations, the amount of plant food in daily life.

According to (very) preliminary results, numerous grindings stones were used at Göbekli Tepe for the processing of cereals and nuts, and very few for ochre and animal skins. But a lot of work will follow to put these observations on a statistically firm basis, and – given the huge amount of information and different methods of analysis – it takes definitely more than one scientist to make (10000) stones speak!

So here is my hive mind, which made my research possible this year: Hajo Höhler-Brockmann (German Archaeological Institute), Julia Meister (Free University of Berlin), Julia Heeb (Village Museum Düppel) and Nils Schäkel (Free University of Berlin) and of course Oliver.

And here is a short history in images from the last months:

1: Sorting grinding stones in the excavation house… (photo: J. Meister)

2: Here is just a part of them! (photo L. Dietrich)

3: Analyzing the use wear with the microscope, making 3D-models and taking samples from the surface: me (left), Julia (right), Hajo (behind).

-

-

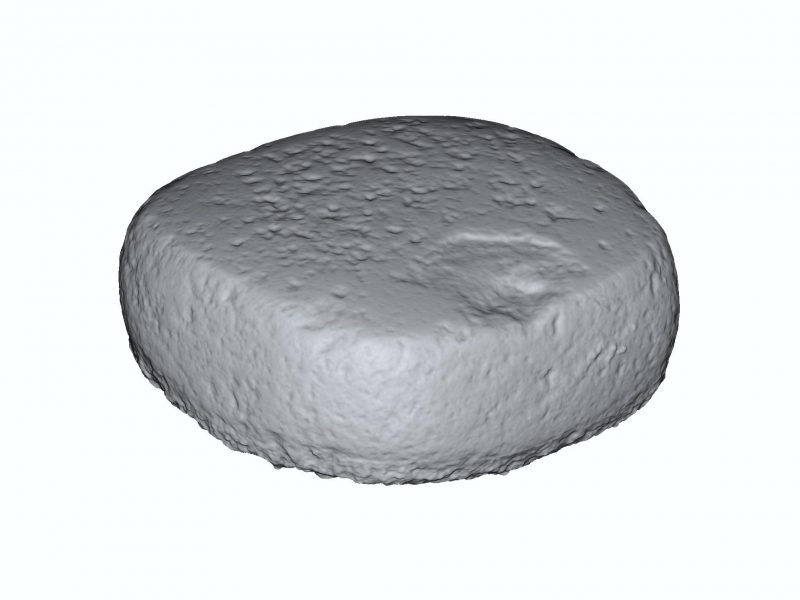

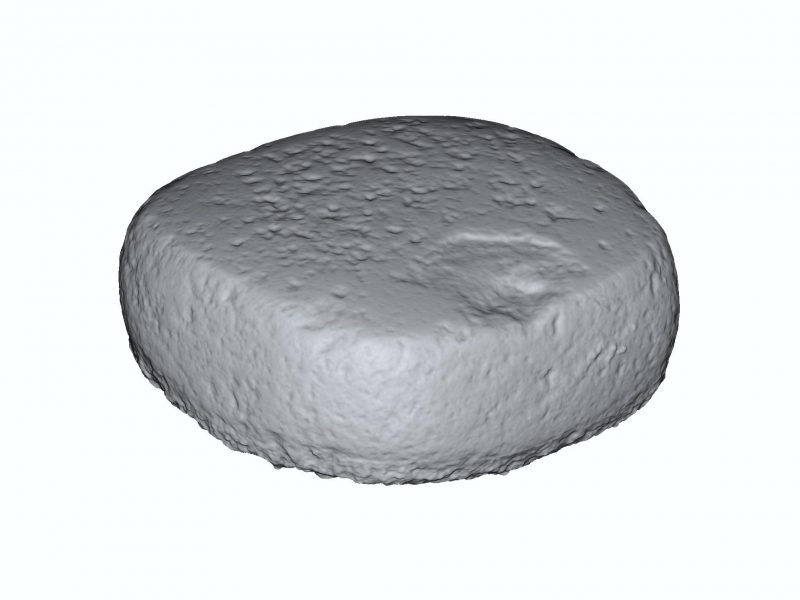

4: Handstone in 3D (model H. Höhler-Brockmann, copyright DAI).

-

-

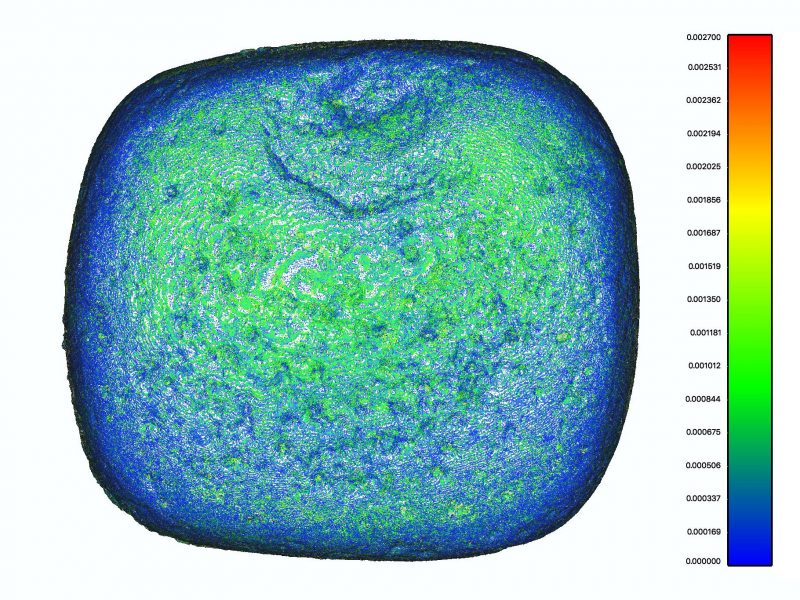

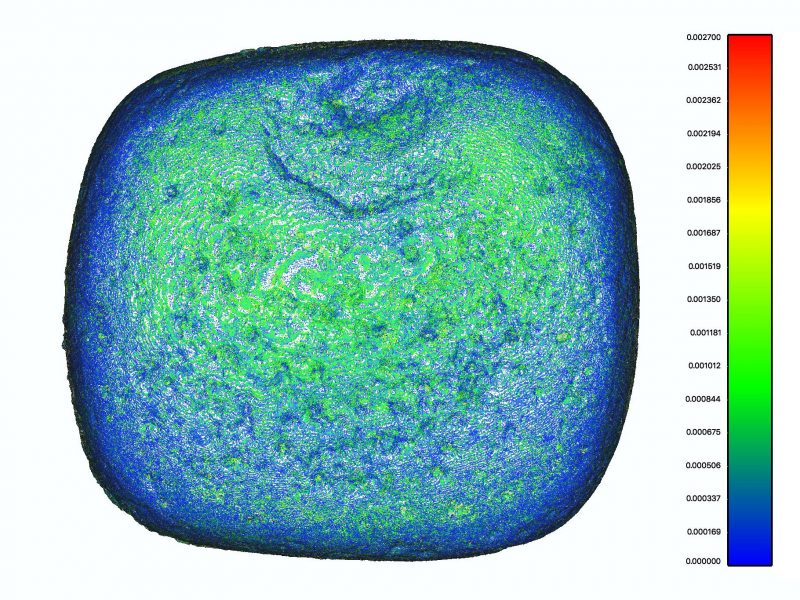

4: Handstone in 3D with analysis of roughness (model H. Höhler-Brockmann, copyright DAI).

4b: …and Hajo taking photos (photo J. Meister).

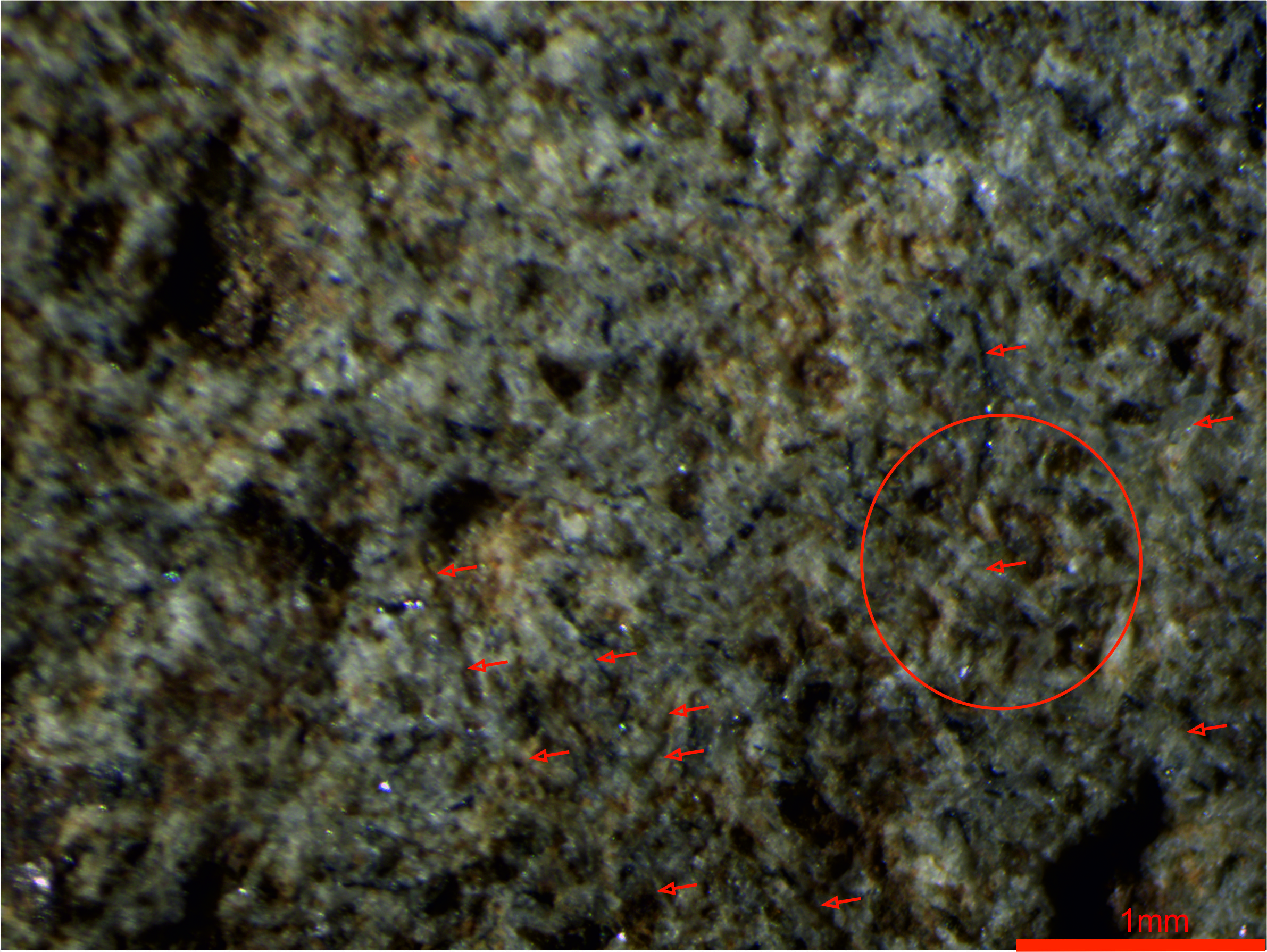

5: Microscopical use-wear of a handstone used most probably for processing einkorn (photo L. Dietrich),

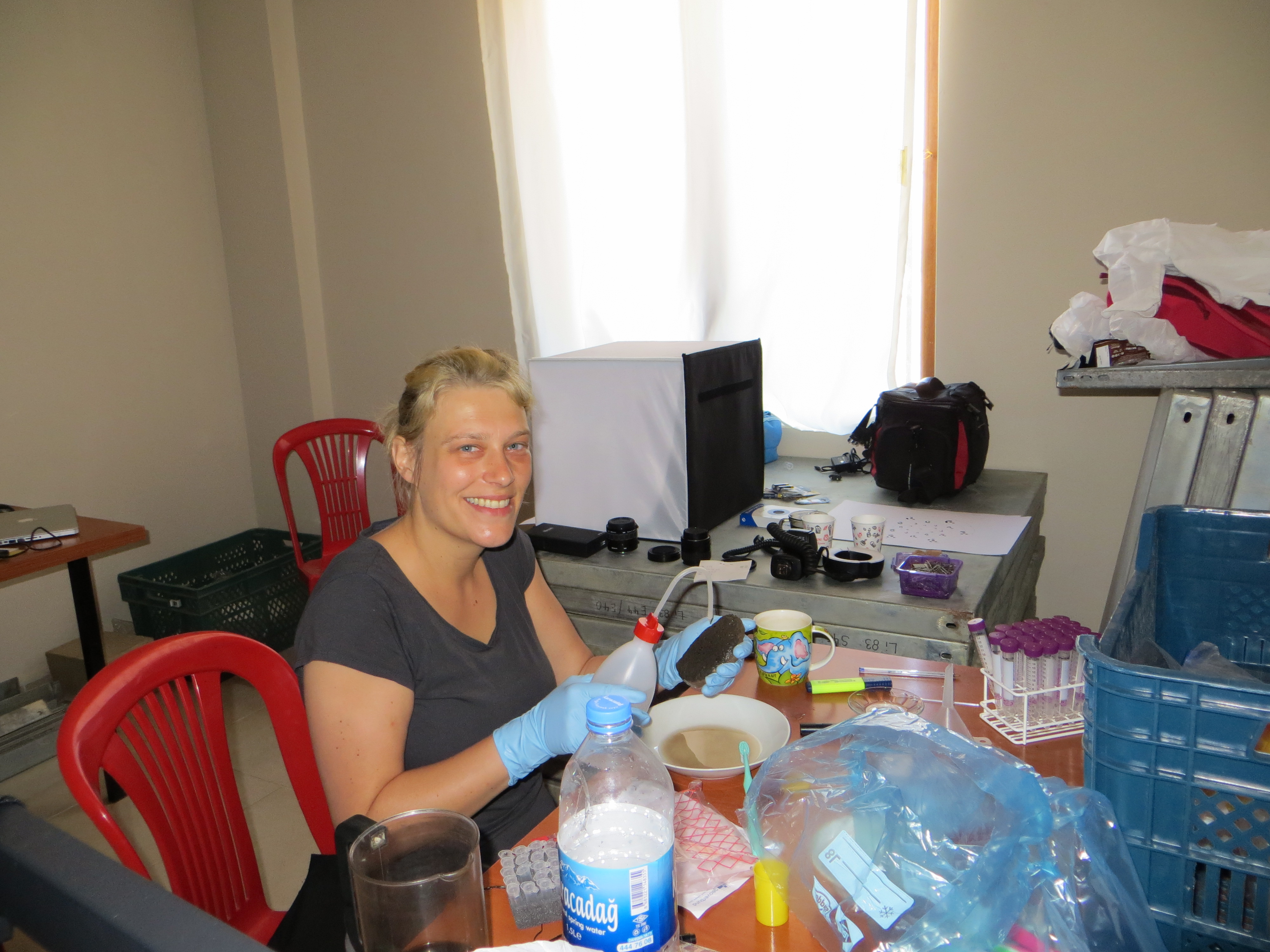

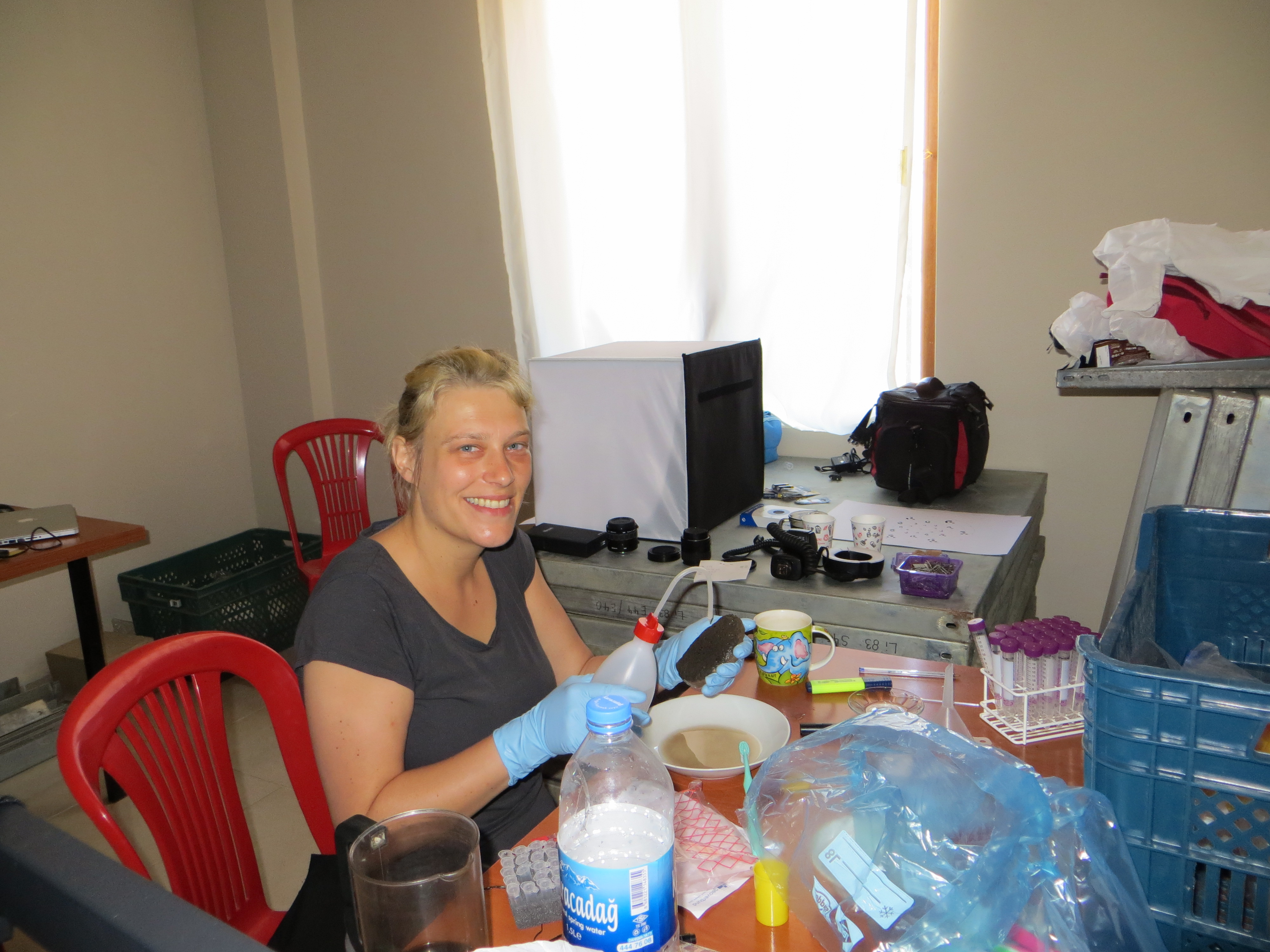

6: …and me analyzing it (photo J. Meister).

7a: Complementary to use wear: sediment samples (photo J. Meister),

7b: …and Julia taking them (photo L. Dietrich)

8: …but also resting in the sunset after a lot of work done! (photo L. Clare)

9a: Back in Berlin: producing experimental grinding stones (photo L. Dietrich),

9b: …of the type used at Göbekli Tepe (photo N. Schäkel),

9c: …grinding einkorn, grinding, and grinding (photo B. Kortmann),

10: …and starting to study use-wear again (photo B. Kortmann)!

And finally: preparing first papers…which is the most exciting part of research!

Recent Comments