Before reading this blog entry we recommend to read the last article on chipped stones from the 5th of July by Jonas Breuers “Chipped Stones: What they are and how they can help understand Göbekli Tepe”

Archaeologists who involve themselves in the work of analysing lithics (synonymous with chipped stones) will early on experience a variety of different possibilities to do so. Already are existing many different systems and methods to reveal as many information as possible from a single silicate rock. Yet, the methods may vary immensely depending on the questions someone researches. Some researchers who work on chipped stones are experts on use-and wear-traces, others are experts in determining raw materials and their origin (e.g. Delvigne et al. 2020; Affolter et al. 2022). In both cases it is necessary to record microscopic features of the chipped stones. At Göbekli Tepe our most recent work focuses on typological and technological developments. Therefore, we record mainly macroscopic visible features on the researched lithics. Some of those are descriptive others are metric. A difficulty is that recording all the features of an artefact takes a huge amount of time and since the number of artefacts at Göbekli Tepe is enormous it is only possible to research small areas in detail. From the results of those in detail researched artefact assemblages we determine historical existing patterns which apply to the whole site.

Next, we shall give an insight into the process of recording artefacts. First and maybe most important is to give every artefact an individual number, so it will always be recognizable. Afterwards the metric values of every single piece are taken. To record weight, length, width and thickness a calliper, a scale and a measuring box are needed (as seen in Fig. 1). While measuring the artefact its condition needs to be considered as well. Is it complete? If not, what kind of fractures does it show? and so on. Combined with the metric values this can for example help to interpret the nature of the researched lithic assemblage, does it consist of disposal and waste materials or is it a cache where blanks or tools were stored.

Furthermore, alterations of the artefacts are recorded. Such can occur through heat, cold and wind as well as through physical and chemical processes connected to the soil an artefact was buried in. Thermic alterations are often visible through frost fractures, “pot lid” fractures, crazing and even change of colour of the raw material, just to name a few (Inizan et al. 1999, 91-92; Floss 2012, 101-104). Physical and chemical processes on the other hand may result in a patination of the artefact which often changes the surface colour and sometimes roughness of the artefact. Even the weight may be affected. The origin and occurrence of different patination is a complex matter. While alterations through cold, wind and chemical processes are often caused by natural developments, alterations through heat are typically connected to human activities, either direct or indirect. People could have used heat to alter certain traits of chipped stones to ease the production of blanks from an otherwise unfavourable raw material or they disposed unwanted chipped stones and tools in a fire pit. Those kinds of alterations tell us a lot about the “life history” of an artefact and how it was handled. In this regard it opens up questions about the chronology of the artefact, which alteration happened when, was the artefact still in use or already disposed et cetera.

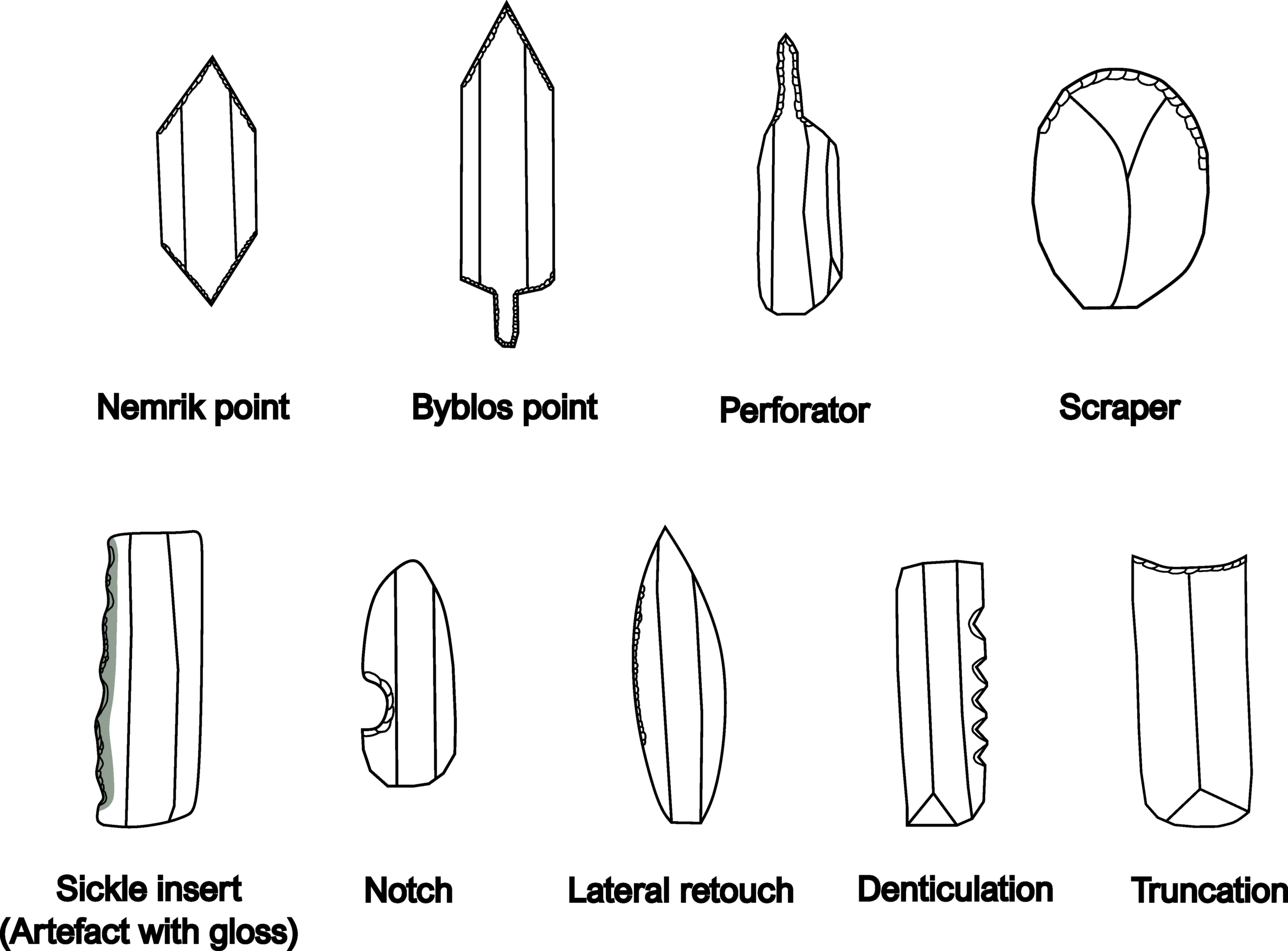

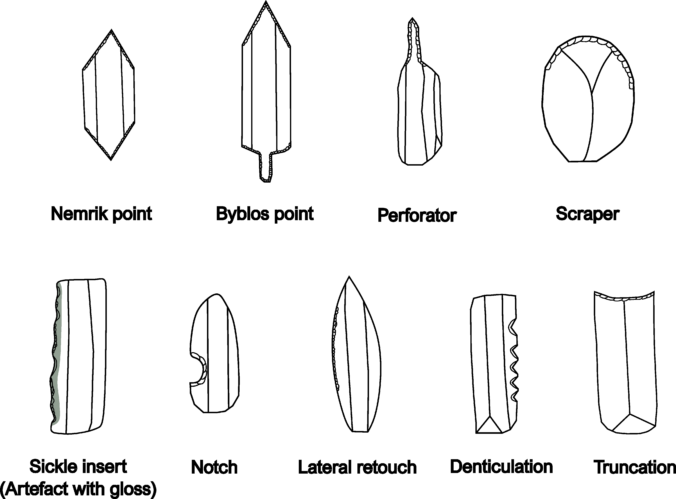

Thanks to their favourable physical properties silicate rocks were used to produce tools, but like in any other industry during the production a lot of refuse emerges. The same goes for Göbekli Tepe where the majority of chipped stones we find are remainders of the production process. Thereby holding information on the used technics from historical flint knappers. Therefore, the relevance of such pieces is not to be underestimated. Because of the physical traits of the lithics different knapping technics also affected the raw material in different ways and intensity. Some features like the extensity of the bulb and shape of butt (= rest of the striking platform, that remained on the blank) can inform us about the used percussion methods like direct and indirect strike or pressure knapping and if the used hammer was either of hard material like quartz or soft material like antler or bone. Identifying the used technics may help archaeologists to discern technological developments and networks of shared knowledge. Going on, one of the major aspects in recording lithic artefacts is, of course, to determine if they were modified into a tool or not. Most tools are defined by shape and type of alteration. To produce the desired shape the edges of blanks, either blades or flakes, were altered by different kinds of fine knapping called retouch. Angle, extent and positioning help to determine the type of retouch (e.g. Inizan et al. 1999, 81; Shea 2013, 170-171). While the type of retouch may in some cases be influenced by the personal preferences of a flint knapper, it often depends on the planned function of the created tool. For an arrowhead a sharp point may be needed, for a perforator a drill like front, for a scraper a steep angled edge. Of course, not always corresponds the description of a tool with its historical function. Most tools were used in a variety of activities and were multifunctional, dependent on the need of its user. Not different from today, where in an extreme case someone may miss a screwdriver and decides to use a knife or key instead. Therefore, the discrimination of tools is firstly a typological one. Still, tools may hold information about knapping traditions, exchange of knowledge and even identity (see Breuers 05.06.23, Tepe Telegrams).

After having recorded all the different features of the chipped stone artefacts like raw material, condition, size, weight, shape, modifications and so on, it is time to analyse the materials. Usually this is done after or in between the field campaigns and not at Göbekli Tepe itself. All the gathered information is processed through comparison and statistical methods, which is the most time-consuming part of the work. We try new statistical methods, interpret the results and sit in the library to compare them with the information from other archaeological sites. Of course, nowadays a lot is eased through Computers and the possibilities of the internet, yet we may only work 40 days a year with the artefacts available and the rest of the year we work with the recorded data, photographs, drawings and documented information from the field work.

References

Affolter, J., H. Wehren, L. Emmenegger 2022. Determination method of silicites (siliceous raw materials): An explanation based on four selected raw materials. In: Quaternary International 615, 33–42.

Delvigne, V., P. Fernandes, C. Tuffery, J.-P. Raynal, L. Klaric 2020. Taphonomic methods and a database to establish the origin of sedimentary silicified rocks from the Middle-recent Gravettian open-air site of La Picardie (Indre-et-Loire, France). In: Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Vol. 32.

Floss, H. 2012. Steinartefakte – vom Altpaläolithikum bis in die Neuzeit. Tübingen: Kerns Verlag.

Inizan, M.-L., M. Reduron-Ballinger, H. Roche and J. Tixier 1999. Technology and Terminology of Knapped Stone (Tome 5). Nanterre: Cercle de Recherches et d’Etudes Préhistoriques.

Shea, J. J. 2013. Stone tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic near East: a guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Further Reading

Beile-Bohn, M., C. Gerber, M. Morsch and K. Schmidt 1998. Neolithische Forschungen in Obermesopotamien. Gürcütepe und Göbekli Tepe. Istanbuler Mitteilungen 48: 5-78.

Breuers, J. 2022. Diachrone Studien zur Lithik des Göbekli Tepe: Locus 166, Raum 16 und die Sedimentsäule aus Gebäude D. Köln: https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/62530/

Breuers, J. and M. Kinzel 2022. “[…] but it is not clear at all where all the […] debris had been taken from […]”: Chipped Stone Artefacts, Architecture and Site Formation Processes at Göbekli Tepe. In: Y. Nishiaki, O. Maeda and M. Arimura (Eds.). Tracking the Neolithic in the Near East. Lithic Perspectives on Its Origins, Development and Dispersals: 469–486. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Clare, L. 2020. Göbekli Tepe, Turkey. A brief summary of research at a new World Heritage Site (2015-2019). E-Forschungsbericht des DAI 2020. doi:10.34780/efb.v0i2.1012

Schmidt, K. 2000. Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Turkey: A preliminary report on the 1995-1999 excavations. Paléorient 26(1): 45-54. Schmidt, K. 2006. Sie bauten die ersten Tempel. Das rätselhafte Heiligtum am Göbekli Tepe. München: C.H. Beck.

Recent Comments