Part 1: A (Re-) Discovery (1994-1996)

Göbekli Tepe before the start of excavations in 1995 (Photo O. Durgut, copyright DAI).

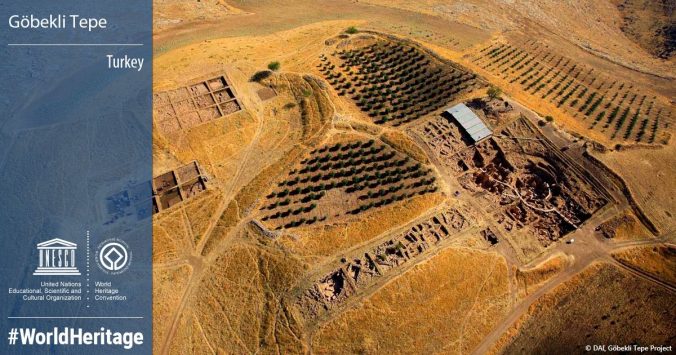

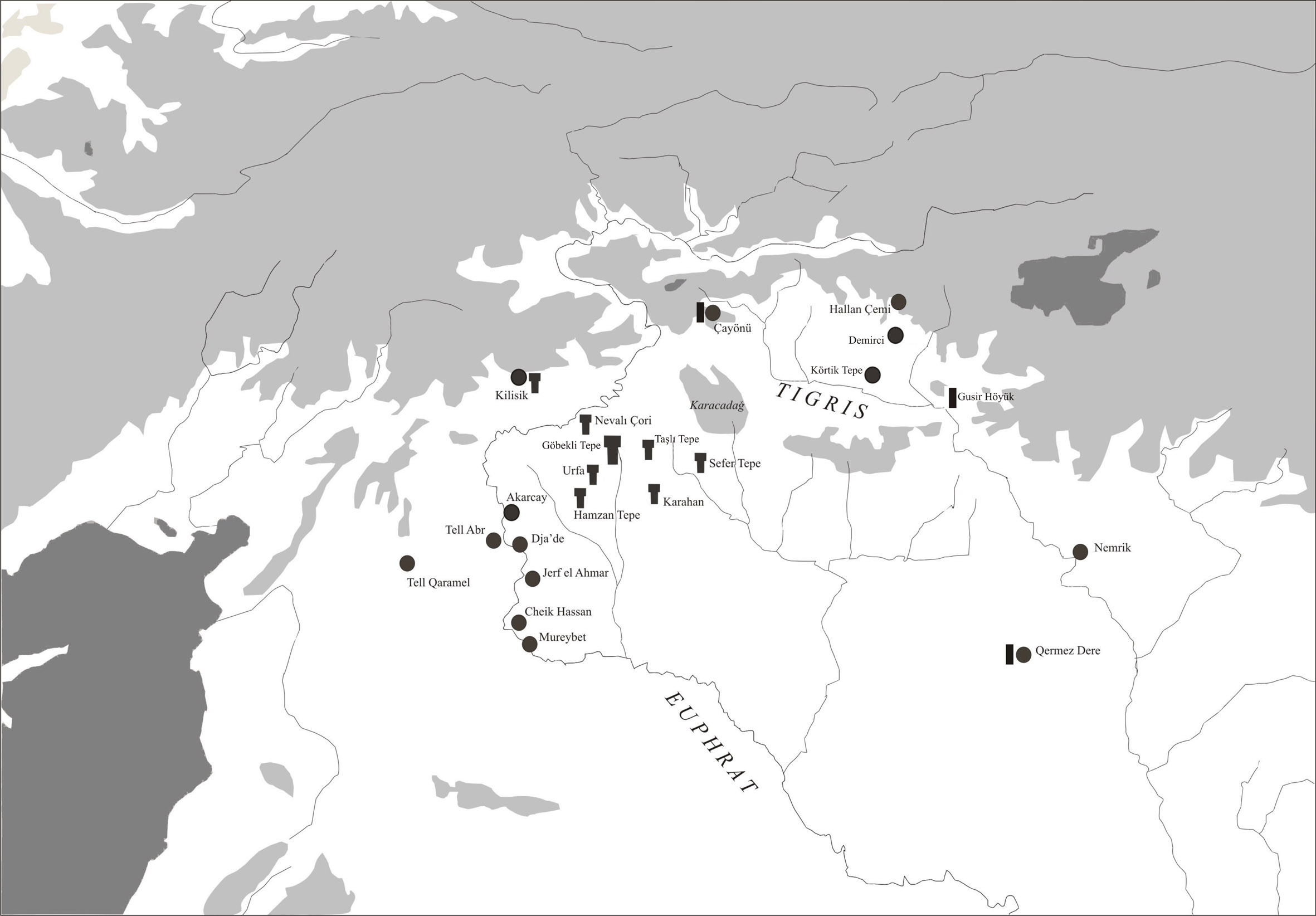

Göbekli Tepe was for the first time recognized as an archaeological site during a large-scale survey project conducted by the Universities of Istanbul and Chicago in 1963. In his account of work in the Urfa province, Peter Benedict describes the site as a cluster of mounds of reddish soil separated by depressions. The slopes were clustered with flint, and he described what he thought to be two small islamic cemeteries. The impressions of the survey team are mirrored in early aerial photographs of the site, taken before excavations started. The reddish-brown tell with its hight of up to 15m and a diameter of 300 m is the only colourful spot on the otherwise barren Germuş mountain range. Situated on the highest point of this geological feature, Göbekli Tepe is a prominent landmark at the edge of the Harran plain. The surveyors identified the materials at Göbekli Tepe as Neolithic, but missed the importance of the site. Further research may also not have seemed possible because of the assumed islamic graveyards.

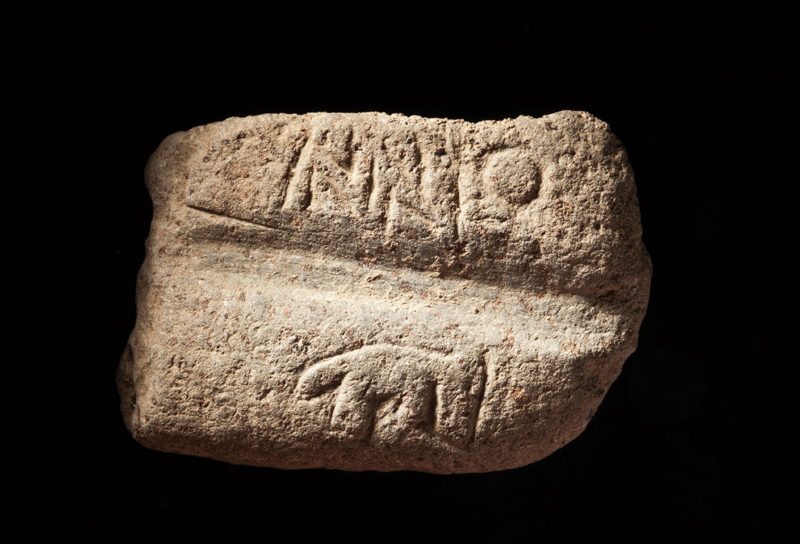

Between 1983 and 1991 large-scale excavations, in fact rescue excavations in advance of the construction of the Atatürk barrage, were under way at another important Neolithic site in the Urfa region, Nevalı Çori. Under the direction of Harald Hauptmann, a Neolithic settlement was excavated that had large rectangular domestic buildings often similar to Cayönü´s channeled buildings. However, excavations revealed also one building (with three construction phases) that was completely different from anything known before in the Neolithic of the Near East. Not only was a large number of monumental stone sculptures discovered, but the rectangular building itself had T-or Gamma-shaped pillars running along the walls, interconnected by a bench, and a pair of T-shaped pillars in the centre. Due to the representation of arms and hands, these pillars could be understood as highly abstracted depictions of the human body.

The “wishing tree” at the highest point of Göbekli Tepe in 1995. The slopes of the tell are littered with finds (Photo M. Morsch, copyright DAI).

Nevalı Çori was finally flooded by the Atatürk Barrage in 1991. But one of the members of the excavation team, Klaus Schmidt (1953-2014), wanted to find out whether there were more settlements like Nevalı Çori hidden in the Urfa region, with special buildings and elaborated stone sculpture. In 1994 he visited all Neolithic sites mentioned in the literature. Drawing on the experience gained at Nevalı Çori, Schmidt was able to identify the ‘tombstones’ at Göbekli Tepe as Neolithic work-pieces and T-shaped pillars. The moment of discovery is best described in his own words [author’s translation based on Schmidt 2006]:

“October 1994, the land colored by the evening sun. We walked through slopy, rather difficult and confusing terrain, littered with large basalt blocks. No traces of prehistoric people visible, no walls, pottery sherds, stone tools. Doubts regarding the sense of this trip, like many before with the aim to survey prehistoric, in particular Stone Age sites, were growing slowly but inexorably. Back in the village, an old man had answered our questions whether there was a hill with çakmaktaşı, flint, in vicinity, with a surprisingly clear „Yes!“. And he had sent a boy to guide us to that place […]. We could drive only a small part of the way, at the edge of the basalt field we had to start walking […]. Our small group was made up of a taxi driver from the town, our young guide, Michael Morsch, a colleague from Heidelberg, and me. Finally we reached a small hill at the border of the basalt field, offering a panoramic view of a wide horizon. Still no archaeological traces, just those of sheep and goat flocks brought here to graze. But we had finally reached the end of the basalt field; now the barren limestone plateau lay in front of us. […] On the opposed hill a large mound towered above the flat plateau, divided by depressions into several hilltops. […] Was that the mound we were looking for? The ‘knocks’ of red soil Peter Benedict had described in his survey report, Göbekli Tepe, or to be more precise, Göbekli Tepe ziyaret? […] When we approached the flanks of the mound, the so far gray and bare limestone plateau suddenly began to glitter. A carpet of flint covered the bedrock, and sparkled in the afternoon sun, not unlike a snow cover in the winter sun. But this spectacular sight was not only caused by nature, humans had assisted in staging it. We assured ourselves several times: These were not flint nodules fragmented by the forces of nature, but flakes, blades and fragments of cores, in short artifacts. […] Other finds, in particular pottery, were absent. On the flanks of the mound the density of flint became lower. We reached the first long-stretched stone heaps, obviously accumulated here over decades by farmers clearing their fields […]. One of those heaps held a particularly large boulder. It was clearly worked and had a form that was easily recognizable: it was the T-shaped head of a pillar of the Nevalı Çori type…”.

S1, the first test trench at Göbekli Tepe (Photo M. Morsch, copyright DAI).

At the moment of its re-discovery in 1994, Göbekli Tepe was nearly untouched by modern activities. The tell could be reached only by foot or horse. The only use, agriculture without deep ploughing, was documented by the extensive ‘walls’ of stones cleared from the fields. Due to heavy winter rains, the possibilities for agriculture are good throughout the region, but Göbekli Tepe is the only spot of arable land in the wider area.

Systematic survey preceded fieldwork. It resulted in a wide range of finds, including sculptures not unlike the ones already known from Nevalı Çori. Excavation work was initiated by Klaus Schmidt the following year, as a cooperative project with the Museum of Şanlıurfa under the direction of Adnan Mısır and the Istanbul branch of the German Archaeological Institute under the direction of Harald Hauptmann.

A first test trench was opened at the base of the southeastern slope, where a modern pit had been cut through a terrazzo floor. Already in this first excavation area a peculiarity of the site was recognized: the tell is not formed mainly of earth and loam. Göbekli Tepe’s sediments are largely made up of limestone cobbles, bones and flints, mixed with relatively little earth. The trench further revealed rectangular buildings characteristic for what was later determined as Layer II, dating to the early and middle PPN B. Two rests of pillars further confirmed the similarities between Göbekli Tepe and Nevalı Çori.

Enclosure A in 1997 (Photo M. Morsch, copyright DAI).

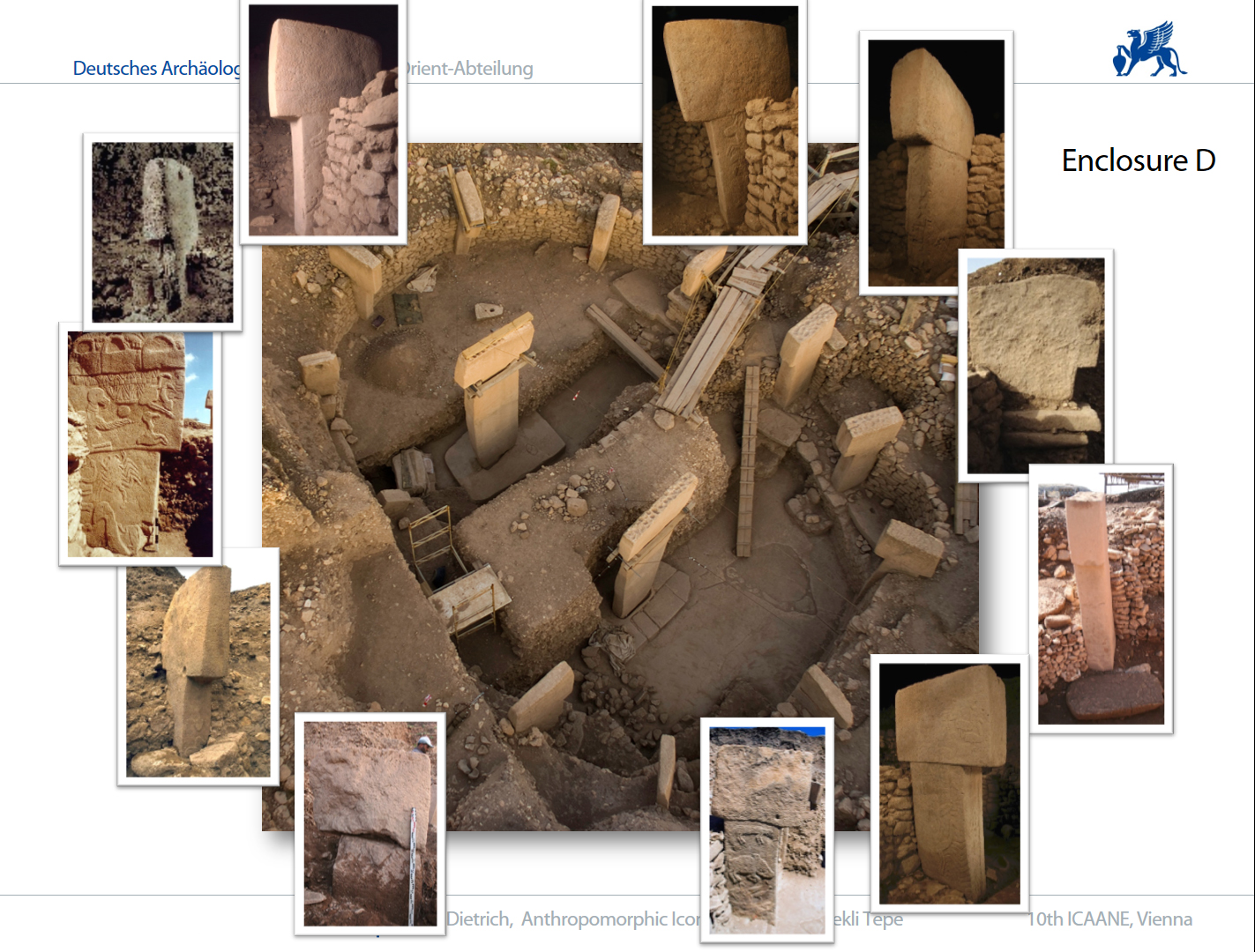

Excavation work did not continue in this area in the next year. During the first field season one of the landowners had started work to clear his field in the southeastern depression of stones that hindered ploughing. He had dug out the heads of two large T-shaped pillars and had already started to smash one pillar head with a sledgehammer. Fortunately he could be persuaded to stop, and in the 1996 work started in this area. What came to light here was the first of the monumental enclosures of Göbekli Tepe´s older layer (Layer III).

-

-

Pillar 1 in Enclosure A shows a net-like pattern formed of snakes and a ram (Photo: C. Gerber, coopyright DAI).

-

-

Pillar 2 in Enclosure A with a vertical sequence of three motifs: bull, fox and crane (Photo: C. Gerber, copyright DAI).

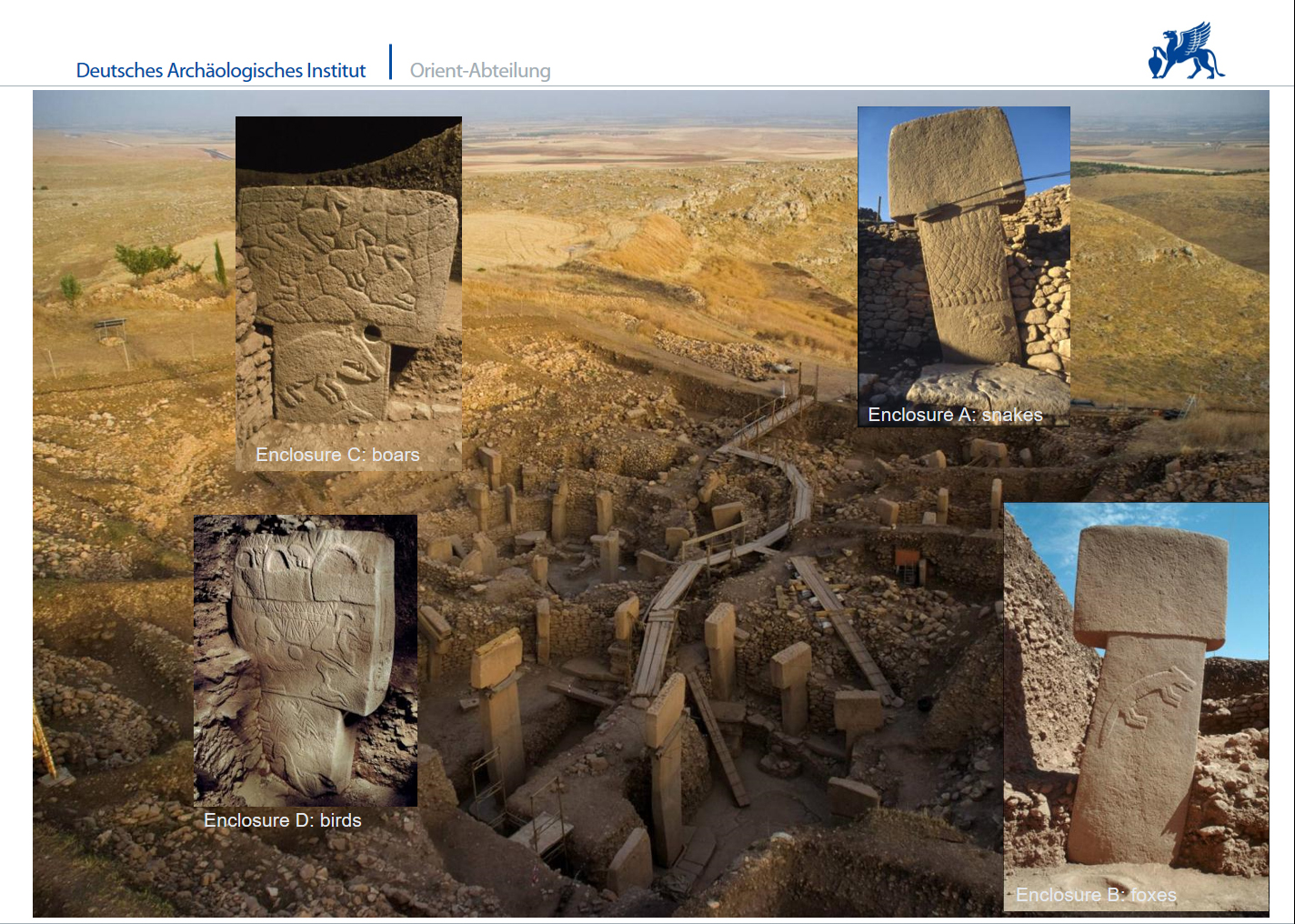

The ground plan of what was later called Enclosure A appears more rectangular than round. Pillars 1 and 2, the central pillars of Enclosure A nearly destroyed by the farmer, were excavated down to the level of the stone bench of the enclosure. Both pillars are richly adorned with reliefs. Particularly striking is a net-like pattern, possibly of snakes, on the left side of Pillar 1. The front side of this pillar carries a central groove running vertically from below the head to its base, covering about one third of its width. This groove and the raised bands to either side are decorated with five snakes in bas-relief. It is most likely that they represent a real object, some kind of stola-like garment.

Pillar 2 carries on its right side a vertical sequence of three motifs: bull, fox and crane. Its narrower back side is adorned with a bucranium between the vertical bands of a stola-like garment. Insights and experience gained in the last years, particularly with regard to typical motif-arrangement, suggests that Pillar 2 is not in its original position but was at some time moved to this secondary location. In the course of this action, the original back side of the pillar became its front and vice versa. Currently, the number of pillars surrounding the two central figures in Enclosure A lies at four.

The following field seasons have revealed astonishing features and finds at Göbekli Tepe that considerably have changed our image of complexity, creativity and organization of the last hunter-gatherers of southwest Asia.

To be continued – stay tuned for future posts on the fascinating history of research at Göbekli Tepe!

Read the full story here:

Klaus Schmidt, Sie bauten die ersten Tempel. Das rätselhafte Heiligtum der Steinzeitjäger. Die archäologische Entdeckung am Göbekli Tepe. C.H. Beck: München (2006).

Klaus Schmidt, Göbekli Tepe. A Stone Age Sanctuary in South-Eastern Anatolia. ex oriente e.V.: Berlin (2012).

The original survey report by Peter Benedict:

Benedict, Peter. 1980. “Survey Work in Southeastern Anatolia.” In İstanbul ve Chicago Üniversiteleri karma projesi güneydoğu anadolu tarihöncesi araştırmaları – The Joint Istanbul – Chicago Universities Prehistoric Research in Southeastern Anatolia, edited by Halet Çambel and Robert J. Braidwood, 150-91. Istanbul: University of Istanbul, Faculty of Letters Press.

On Nevalı Çori:

Hauptmann, Harald. 1988. “Nevalı Cori: Architektur.” Anatolica XV: 99-110.

Hauptmann, Harald. 1993. “Ein Kultgebäude in Nevali Çori.” In Between the Rivers and over the Mountains. Archaeologica Anatolica et Mesopotamica Alba Palmieri dedicata, edited by Marcella Frangipane, Harald Hauptmann, Mario Liverani, Paolo Matthiae and Machteld J. Mellink: 37-69. Rom: Gruppo Editoriale Internazionale-Roma.

Hauptmann, Harald. 1999. “The Urfa Region.” In Neolithic in Turkey, edited by Mehmet Özdoğan and Nezih Başgelen, 65-86. Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları.

Recent Comments