Göbekli Tepe is often compared with other megalithic architecture. Stonehenge is an example here, others include the temples of Malta, the Taulas of Menorca, or the Moai of the Easter Islands. And fairly often, people also construct or believe in direct relations between these sites.

I believe this partly happens because people tend to categorize things in relation to other things they already know. Especially Stonehenge – for many people the iconic example for megaliths par se – can be found in every popular history book, making such comparisons with other sites with large standing stones, some of them decorated with reliefs, easy. But there is a little more to it. I remember that my schoolbooks used to invoke the idea of a somehow interrelated Neolithic „Megalithic Culture“ that spread throughout Europe by migration. This was in the later 1980ies. Of course by this time the diffusionist view on the spread of megaliths had long been discredited by Colin Renfrew, i.a. based on radiocarbon dates (you can see him talk about this here – external link). But textbooks just hadn’t noticed what was going on in academia. This is, by the way, a problem that archaeologists should address in some way also today.

But back to Göbekli Tepe. As we really get a lot of inquiries regarding possible interrelations of important megalithic sites, I thought I should post a short checklist here to show how different these sites really are. So here they are, in chronological order; please note that I am just writing down the main points from memory, if you have further questions please post them in the comments.

Göbekli Tepe

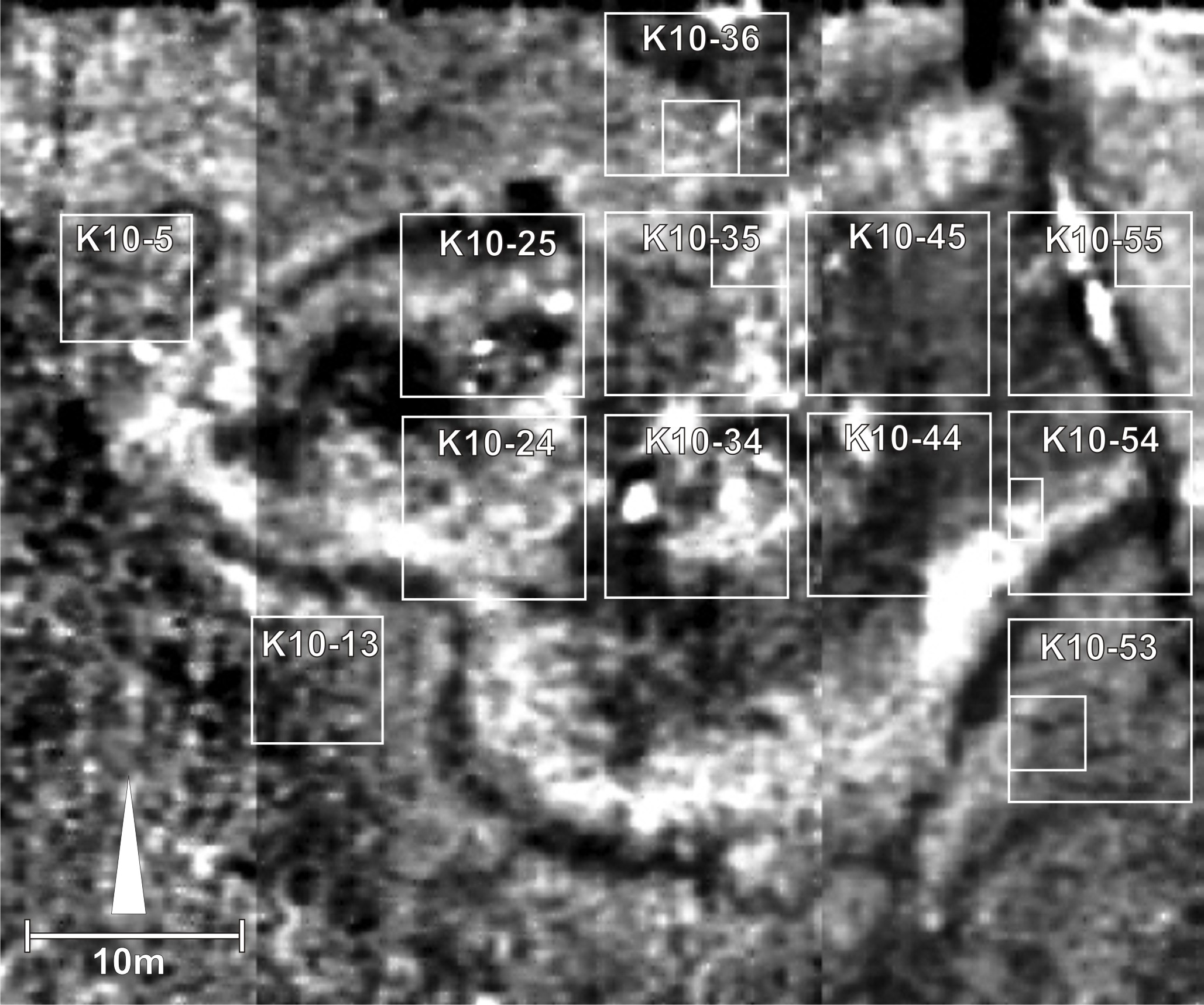

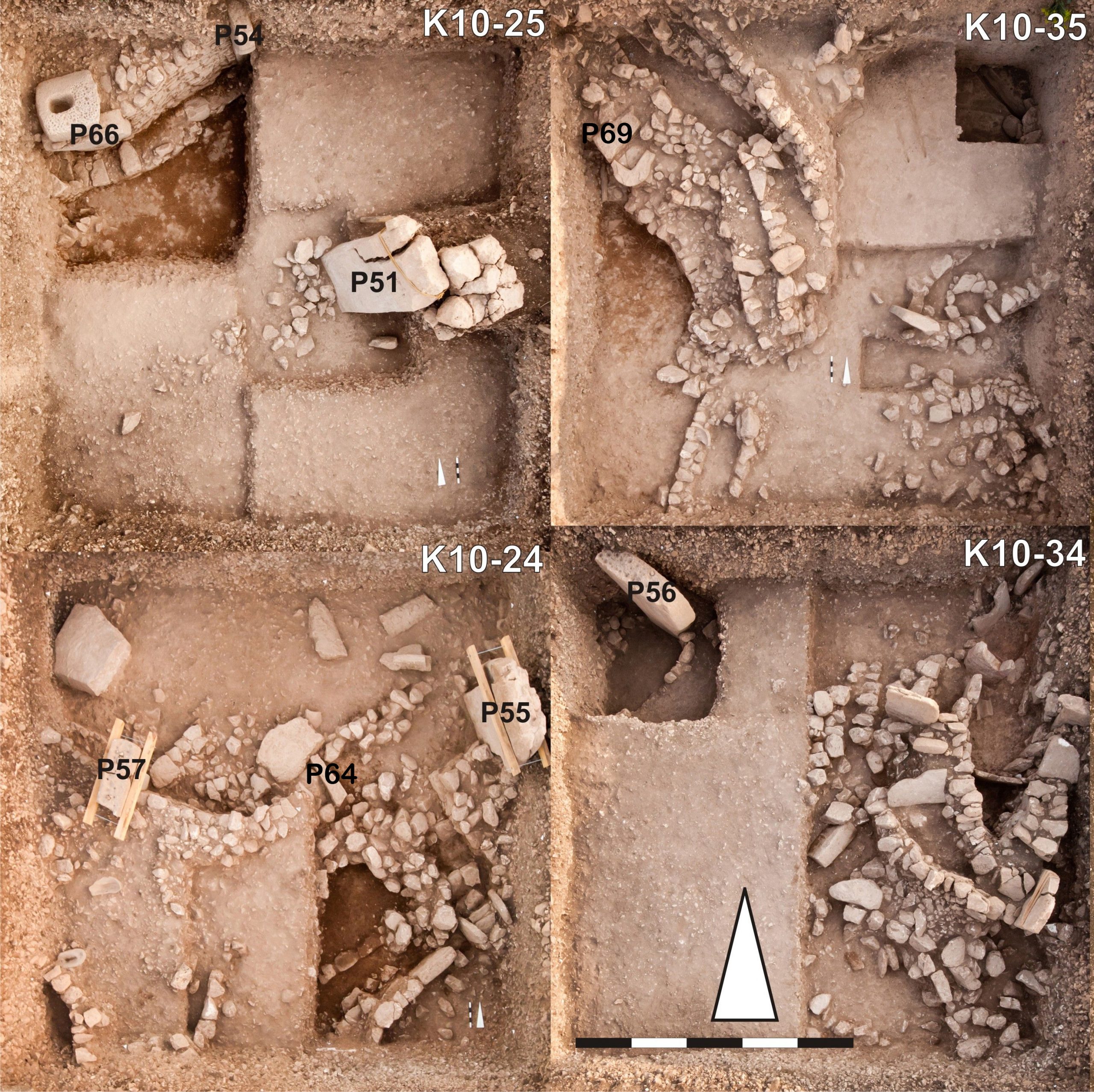

Göbekli Tepe, Enclosure C, illustrating the characteristic layout of the older buildings (copyright DAI, photo K. Schmidt).

Location: southeastern Turkey, on the highest point of the Germus mountain range.

Built / used between: ca. 9500-8000 cal BC, Pre-Pottery Neolithic.

By: Hunter-gatherer groups from a catchment area of about 200km around the site using stone tools.

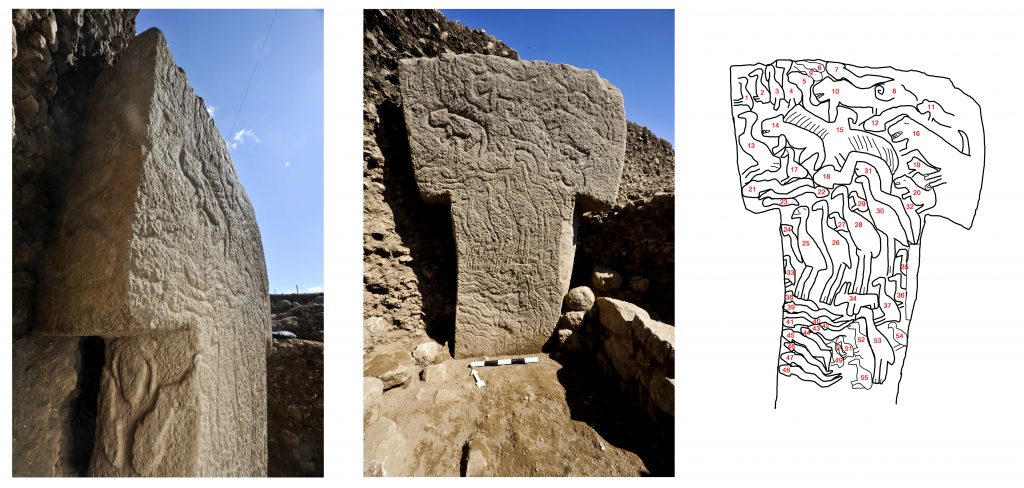

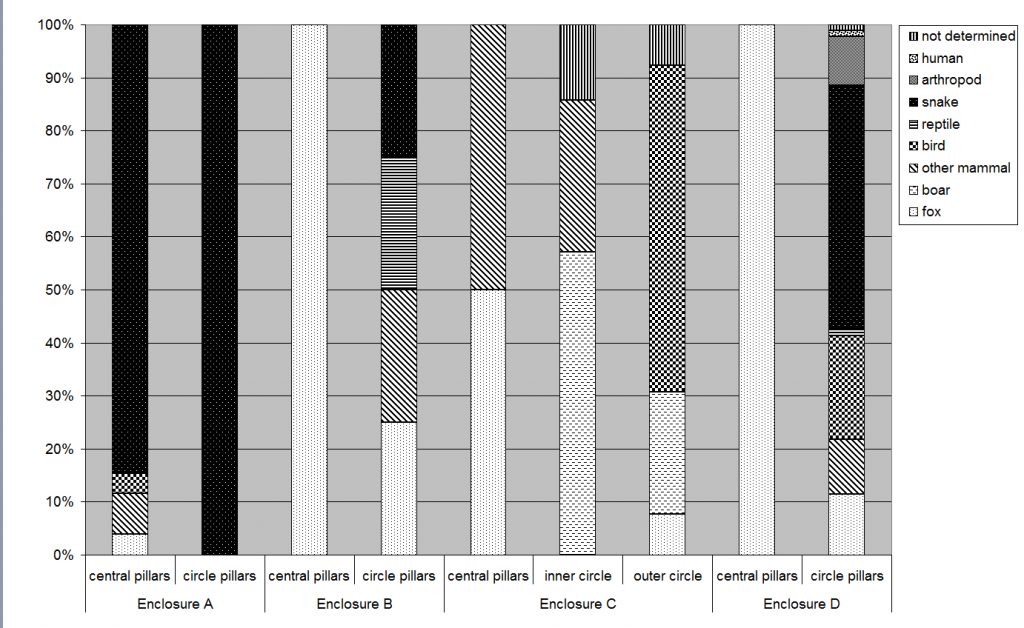

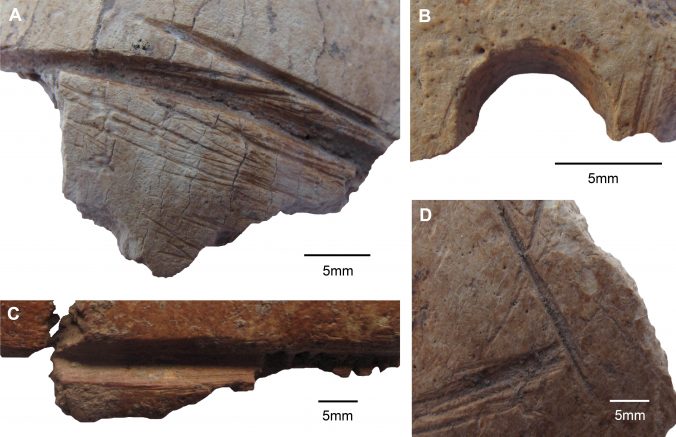

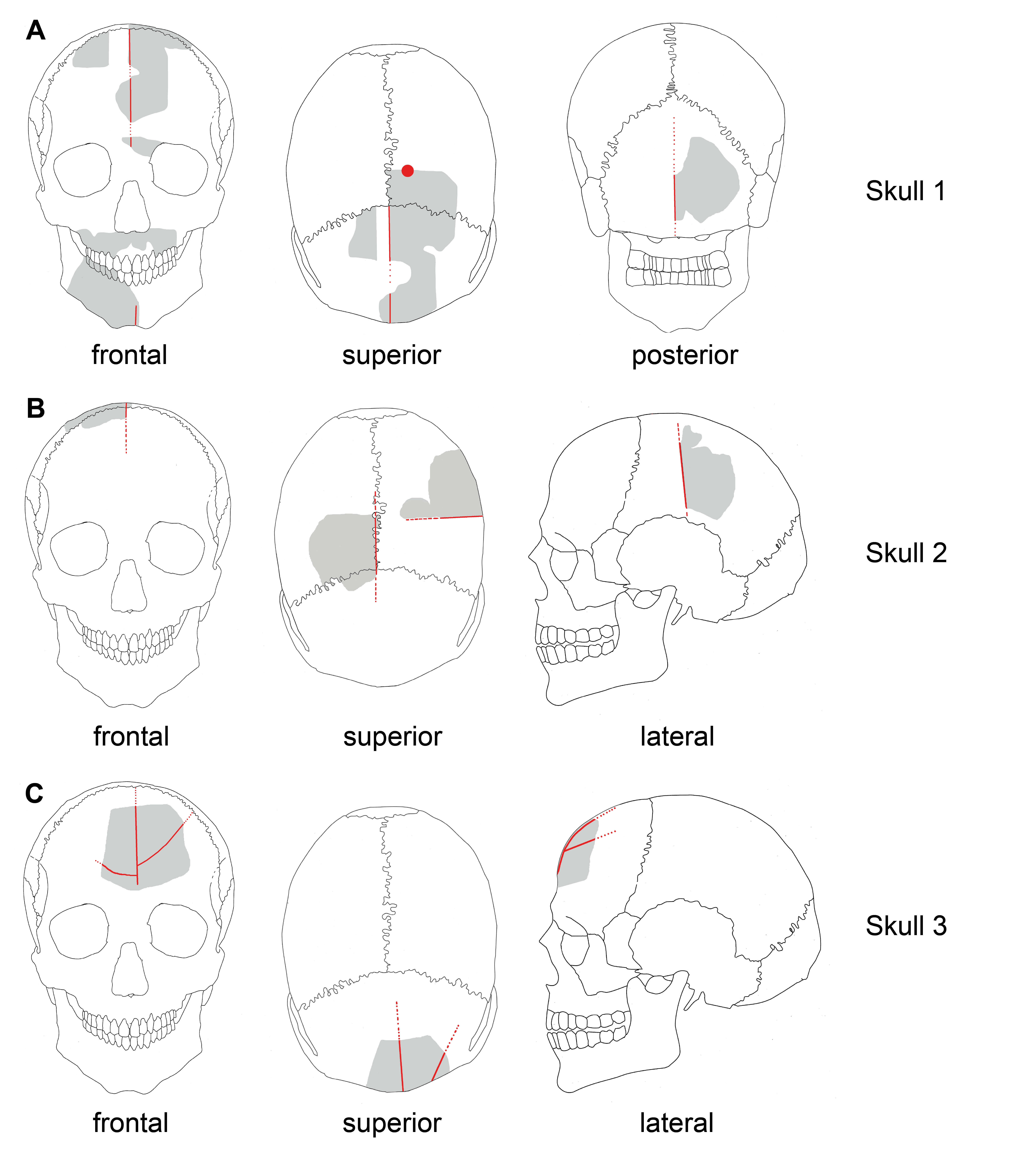

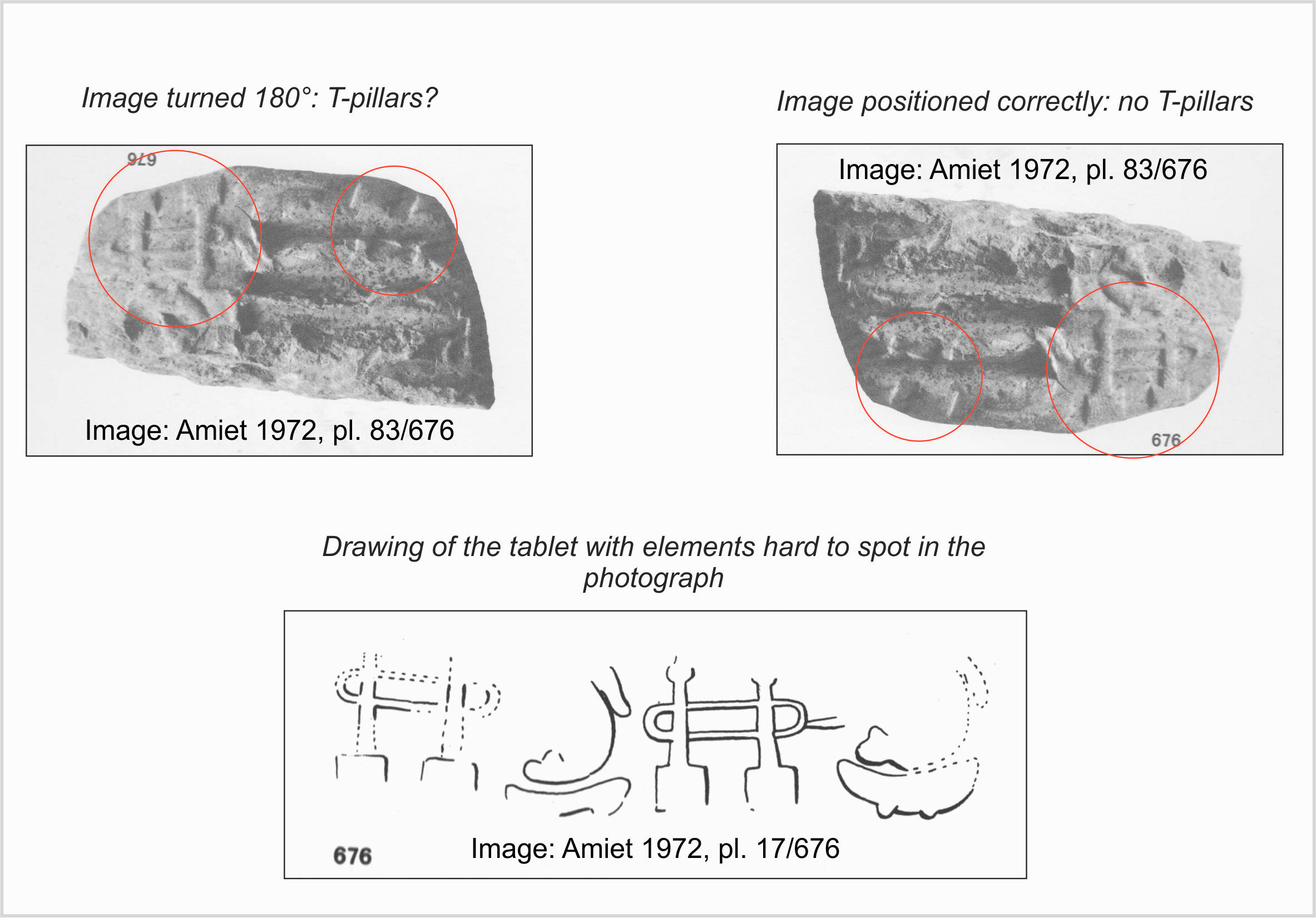

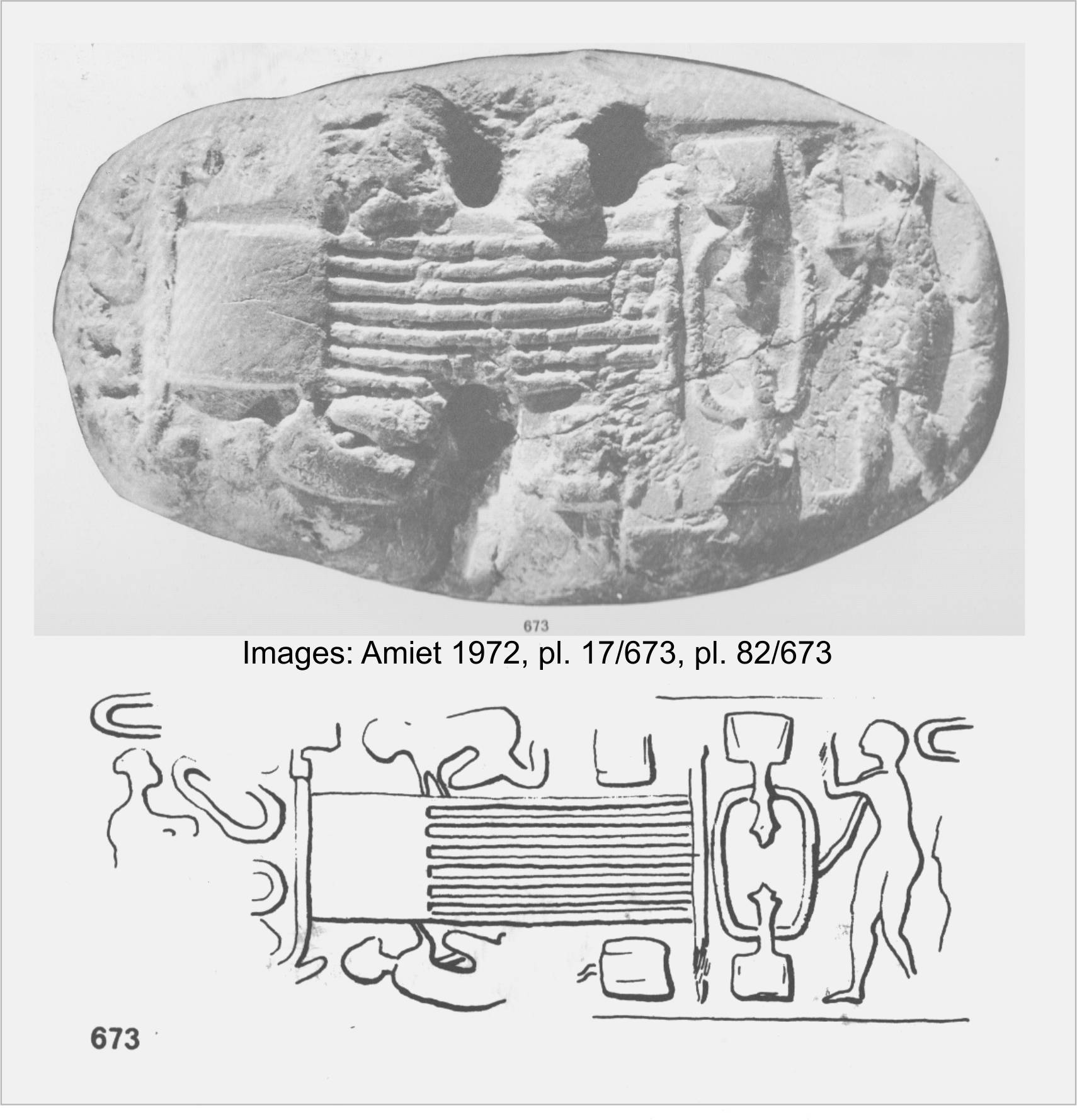

Main characteristics: The oldest layer III (10th millenium BC) is characterized by monolithic T-shaped pillars weighing tons, which were positioned in circle-like structures. The pillars were interconnected by limestone walls and benches leaning at the inner side of the walls. In the center of these enclosures there are always two bigger pillars, with a height of over 5m. The circles measure 10-20m. The T-shape of the pillars is clearly an abstract depiction of the human body seen from the side. Evidence for this interpretation are the low relief depictions of arms, hands and items of clothing like belts and loinclothes on some of the pillars. Often the pillars bear further reliefs, mostly depictions of animals, but also of numerous abstract symbols. Layer III is supraposed by layer II, dating to the 9th millenium BC. This layer is not characterised by big round enclosures, but by smaller, rectangular buildings. The number and the height of the pillars are also reduced. In most cases only the two central pillars remain, the biggest measuring around 1,5m.

Miniature madel of a Maltese temple from Mġarr, Museum of Valletta (Photo: O. Dietrich).

Temples of Malta

Location: Malta and Gozo, islands in the Mediterranean Sea, temples are spread widely, sometimes forming clusters.

Built / used between: The Neolithic and the Bronze Age. However, the actual ‘Temple Period’ falls within the 4th millennium BC and the 3rd millennium BC. Temples were constructed using stone tools.

By: The local population of these islands, evidence for external contact is rare.

Main characteristics: The temples are made of limestone orthostats forming walls. They usually have an oval forecourt and a facade with an entrance made up of three megaliths, of which two are supporting the third, forming a trilithon. Inside is a passageway of similar construction leading to an open paved space flanked by apses. Decorations inside the temples include spiral motifs, animals and surfaces covered entirely with drilled holes.

Further reading: For an easily accessible and well written overview: Trump, D.H. 2002. Malta: Prehistory and Temples. Midsea Books: Malta. Also, check out the Website of the UNESCO World Heritage List entry [external link].

Stonehenge, features of all construction phases (Drawn by en:User:Adamsan, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons).

Stonehenge

Location: Wiltshire, England.

Built / used between: several building phases between 3100 and 1600 BC.

By: People from a wider catchment area, some of the raw material was transported over vast distances, e.g. the so-called bluestones from nowadays Wales, metal tools available during the later phases.

Main characteristics: The iconic view of Stonehenge shows a ring of standing stones around 4 m high, partly still forming trilithons. But Stonehenge has a highly complex building history that includes many changes to the layout of the site, accumulating to two megalithic stone rings and two orthostat arrangements surrounded by wooden posts and earthworks. Further, Stonehenge is part of a Neolithic/Bronze Age cultural landscape marked by earthworks and burial mounds.

Further reading: Mike Parker Pearson is the person to ask about Stonehenge and here is a great overview article that´s also freely accessible: Parker Pearson, M. 2013. Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present. Archaeology International. 16, 72–83. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334

Taula of Trepuco (Juan Costa Archiv, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons).

Taulas

Location: On the Balearic island of Menorca.

Built / used between: roughly between 1000 and 300 BC.

By: The local, so-called Talaiotic Culture, which is restricted to Menorca.

Main charateristics: Taulas (meaning tables) are formed of a vertical pillar (sometimes made up of several stones) on which another stone rests horizontically. They are around 4 m high and usually stand within u-shaped buildings.

Further reading: There is not so much published about the Taulas in English and available to access freely online, if you are able to read Spanish, this artcle may be a good start: Daniel Albero Santacreu, D.A. 2009-2010. Análisis arquitectónico de los recintos de taula de la isla de Menorca: significación técnica y simbólica de los parámetros constructivos. Mayurqa 33, 2009-2010: 77-94 [external link].

Moai at Ahu Tongarik (Rivi, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons).

Moai

Location: Easter Island, Polynesia.

Built / used between: 1250-1500 AD.

By: the Polynesian colonizers of the Easter island.

Main charateristics: Monolithic human figures with facial features, arms/hands, up to 10 m high and integrated into ceremonial sites The letter consist of a levelled plaza, from which a ramp led up to a rectangular platform, where the moai stood.

Further reading: A classic is Routledge, K. 1919. The mystery of Easter Island. The story of an Expedition. London: Hazel, Watson & Winey [external link]. There isa vast amount of literature though, and also an ongoing research project by the German Archaeological Institute [external link].

Conclusion

The sites discussed here may have had similar social functions as centers for gatherings, expressions of belief systems etc. for the societies that built them. But I believe that this short comparison also shows clearly that we are dealing with very different sites indeed, evolving in different timeframes and regions, and rooted in a very specific local cultural background each. Their architecture is hardly comparable. Superficial similarities like the T-shape of GT´s pillars and the Taulas can be explained much better by a similar function, e.g. as roof supports, than by direct interconnections between the builders over large chronological and spatial distances.

Recent Comments