-

-

The ‘Urfa Man’ in the garden of the old Urfa Museum (Copyright DAI, Photo I. Wagner).

-

-

The ‘Urfa Man’ in the garden of the old Urfa Museum (Copyright DAI, Photo I. Wagner).

-

-

The ‘Urfa Man’ in the garden of the old Urfa Museum (Copyright DAI, Photo I. Wagner).

-

-

The ‘Urfa Man’ in the garden of the old Urfa Museum (Copyright DAI, Photo I. Wagner).

-

-

The ‘Urfa Man’ in the garden of the old Urfa Museum (Copyright DAI, Photo I. Wagner).

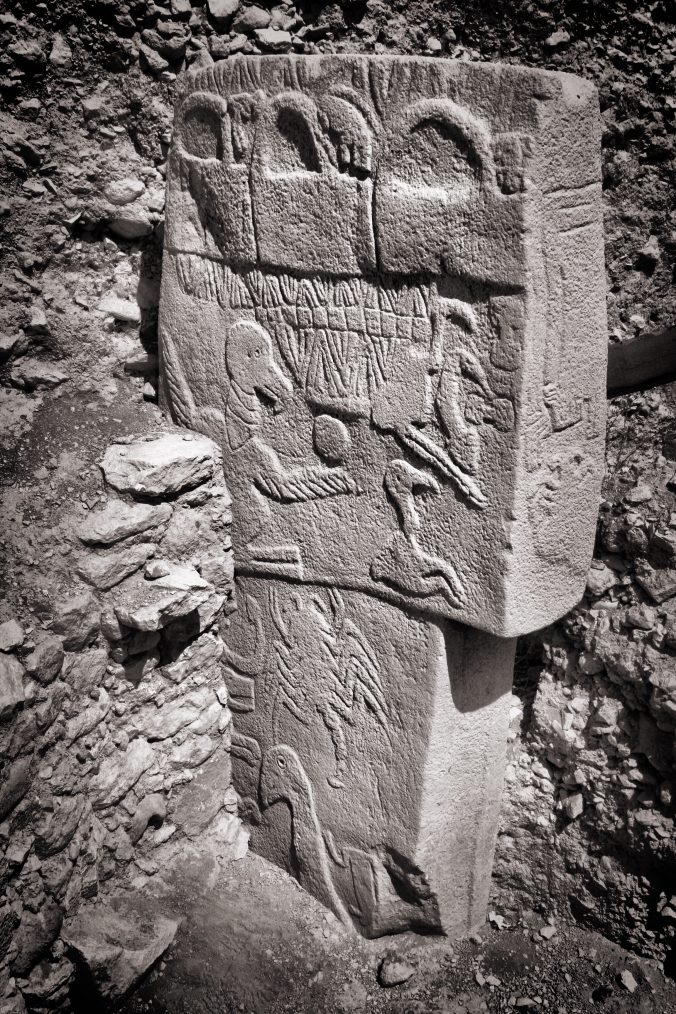

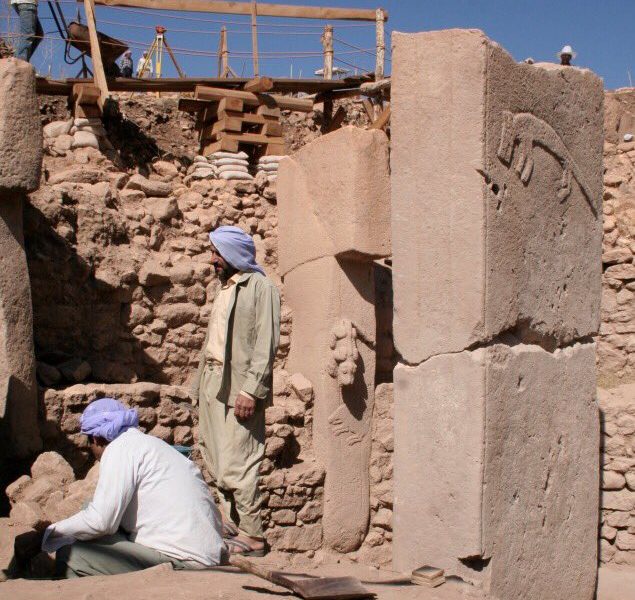

This short post is about the ‘Urfa Man’. Let’s start with an answer to a very common question: no, he is not from Göbekli Tepe. He was found during construction work in the area of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic site at Urfa-Yeni Mahalle / Yeni Yol (Bucak & Schmidt 2003; Çelik 2011; Hauptmann 2003; Hauptmann & Schmidt 2007), broken in four nearly equal pieces.

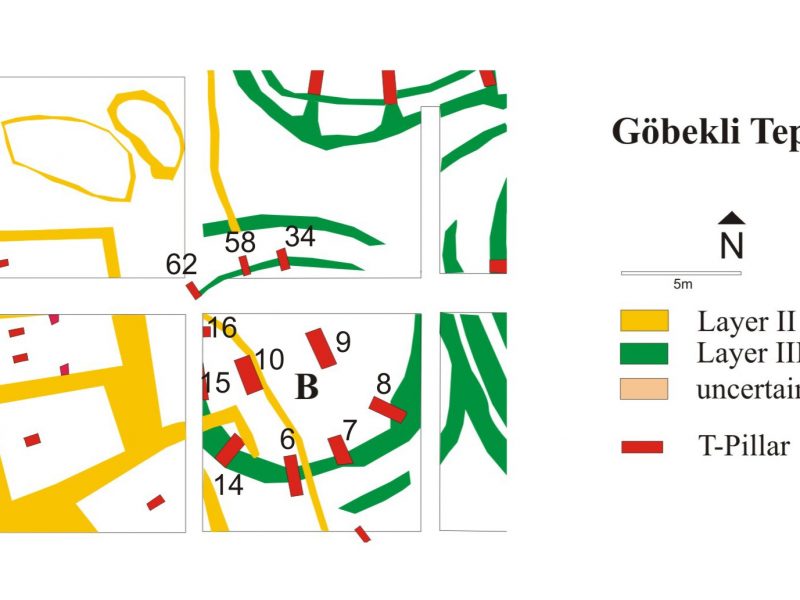

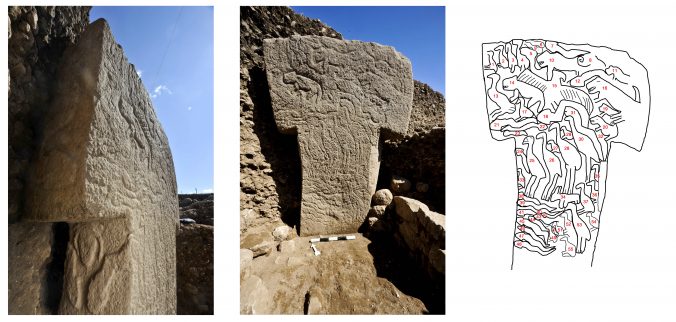

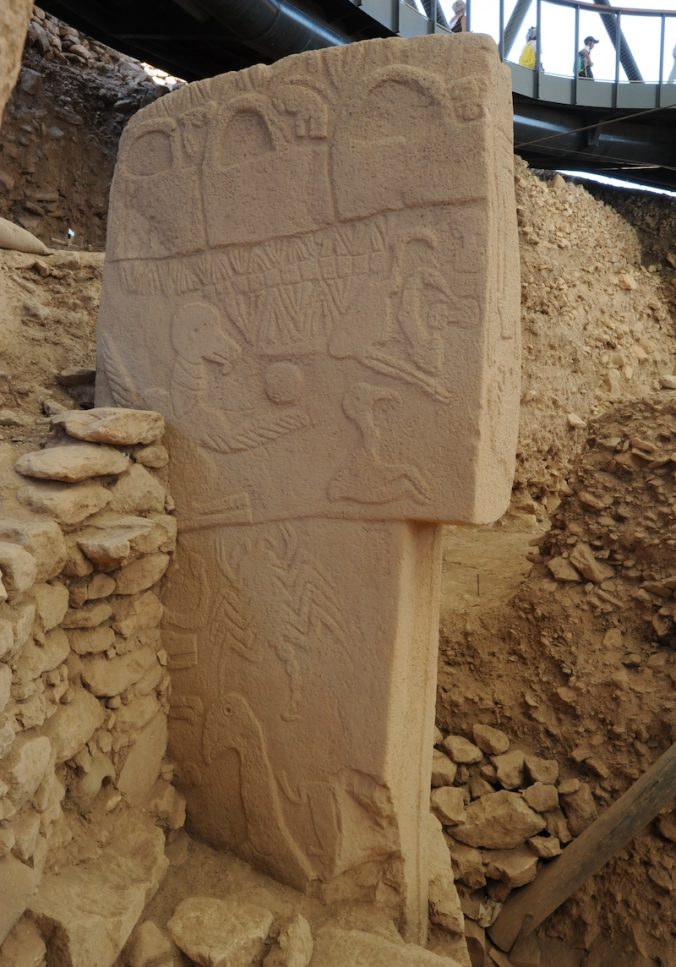

The settlement was largely destroyed, but photos showing the construction work seem to reveal an interesting detail about the site: it featured a small T-shaped pillar (Çelik 2011, 142, Fig. 19), similar to those from Göbekli Tepe’s Layer II. This speaks for a PPN B date, as does the archaeological material recovered (Çelik 2011).

The ‘Urfa man’ himself gives witness to the ability of early Neolithic people to sculpt the human body naturalistically. It is the oldest known statue of a man, slightly larger than life-size. In contrast to the cubic and faceless T-shaped pillars, the ‘Urfa man’ has a face, eyes originally emphasized by segments of black obsidian sunk into deep holes, and ears ; a mouth, however, is not depicted. The statue seems to be naked with the exception of a V-shaped necklace. Legs are not depicted; below the body there is only a conical plug, which allows the statue to be set into the ground. Both hands seem to grab his penis.

As no find context has been recorded for the sculpture, it is hard to evaluate its original function. But there are several fragments, especially heads, of similar sculptures from Göbekli Tepe. At this site, statues like the ‘Urfa Man’ seem to have been part of a complex hierarchical system of imagery directly related to the functions of the circular enclosures. You can find a longer text about this here.

The presence of a sculpture like the ‘Urfa Man’ and of T-shaped pillars are strong evidence for the presence of a special building inside the settlement at Urfa-Yeni Yol. It may have been comparable to the PPN B ‘cult buildings’ of Nevalı Çori (Hauptmann 1993), but this will remain pure speculation.

Bibliography

Bucak, E. & K. Schmidt, 2003. Dünyanın en eski heykeli. Atlas 127, 36-40.

Çelik, B., 2011, Şanlıurfa – Yeni Mahalle, in The Neolithic in Turkey 2. The Euphrates Basin, eds. M. Özdoğan, N. Başgelen & P. Kuniholm. Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yaınları, 139-164.

Hauptmann, H., 1993. Ein Kultgebäude in Nevalı Çori , in Between the rivers and over the mountains. Archaeologica Anatolica et Mesopotamica Alba Palmieri dedicata, eds. M. Frangipane, H. Hauptmann, M. Liverani, P. Matthias & M. Mellink. Roma: Dipartimento di Scienze Storiche Archaeologiche e Anthropologiche dell’Antichità, Università di Roma ‘La Sapienza’, 37-69.

Hauptmann, H., 2003. Eine frühneolithische Kultfigur aus Urfa, in Köyden Kente. From village to cities. Studies presented to Ufuk Esin, eds. M. Özdoğan, H. Hauptmann & N. Başgelen. Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yaınları, 623-36.

Hauptmann, H. & K. Schmidt, 2007. Anatolien vor 12 000 Jahren: die Skulpturen des Frühneolithikums, in Vor 12000 Jahren in Anatolien. Die ältesten Monumente der Menschheit. Begleitband zur großen Landesaustellung Baden-Württemberg im Badischen Landesmuseum 2007, ed. C. Lichter. Karlsruhe: Badisches Landesmuseum, 67-82.

Recent Comments