–

by Fabian Becker, Robert Busch, Mehmet Doğan, Joris Starke

Understanding the dynamics of a river begins with its catchment. This season’s field work has been focused on the corridor of the Selinus river (Bergama Çayı) upstream from the lower Roman city of Pergamon. Geomorphological techniques were used to reconstruct past river dynamics, investigate discharge conditions, and analyze the influence of (modern) human alterations on fluvial processes.

The Bergama Çayı is at the core of the old city center of Bergama. In ancient times, the river – known as Selinos in the Hellenistic world and Selinus by the Romans – and its dynamics were of great importance. Archaeological research in the last decades – partly conducted in the framework of the TransPergMicro-project – has shed light on the ancient measurements that shaped the course of the Selinus river on its way through the ancient city. A famous example of a major intervention in river width, slope, and bedform is the culvert tunneling under the Red Hall Basilica for a distance of about 200 meters. The building research team recently recorded a river embankment and related structures in TransPergMicro, and an artisans’ quarter situated along the banks of the Selinus river was excavated.

Recent fieldwork shifted the focus from the city, where the river is currently being substantially reshaped by the State Hydraulic Works (DSİ), to the river’s valley and catchment area in the Kozak mountains.

Fluvial terraces and past landscapes

Our key to understanding past landscapes in the TransPergMicro project lies in sediment profiles from alluvial environments obtained through percussion drilling (Fig. 1). During this year’s field season, the physical geography groups of Freie Universität Berlin and Ege Üniversitesi İzmir further strengthened their collaboration, ongoing since 2020. For the first time, Doç. Dr. Mehmet Doğan held the official license for the drillings carried out in the Selinus valley. Alongside the TransPergMicro team, three Bachelor’s and Master’s students from Freie Universität and four students from Ege Üniversitesi played an important role in both the fieldwork and the on-site analysis of the recovered cores.

Profiles from three sites along the open Selinus valley revealed a consistent pattern: silty fine- to medium-grained sands overlying the river’s lower terrace. These deposits record the most recent flooding phases of the valley. Radiocarbon dating, conducted in cooperation with the AMS laboratory of TÜBİTAK-MAM, will help establish a chronology of fluvial dynamics and link the results to existing knowledge on human-environment interactions around Pergamon. The findings will also contribute to interpreting the results of this season’s archaeological survey.

Pebbles, discharge, and drift lines

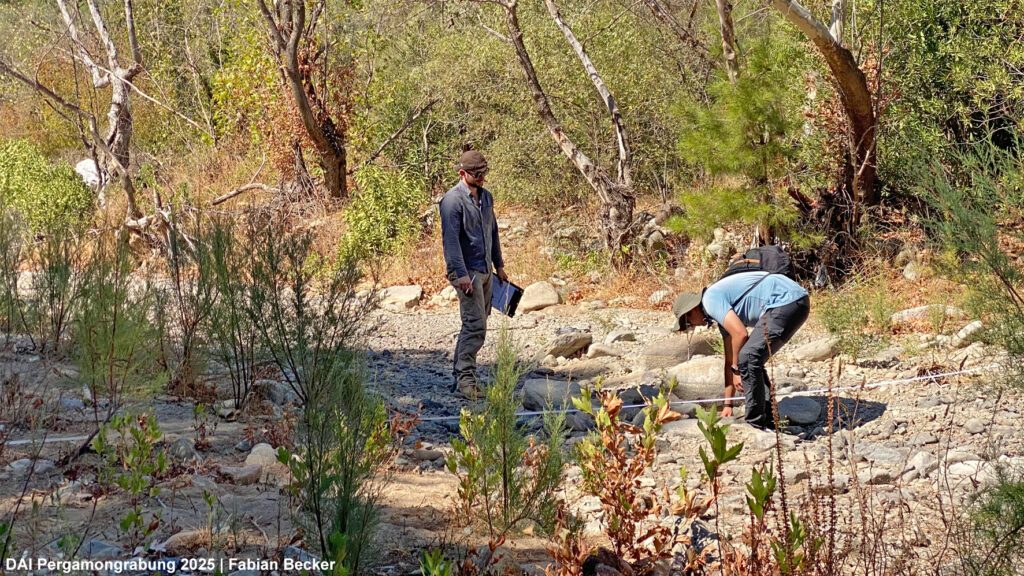

Further research was conducted in the framework of the archaeological survey project. A key tool used in this ongoing work was a modified version of Wolman’s classic pebble count method (Fig. 2). In this method, clasts (pebbles/gravels, cobbles, boulders – all of which are clearly larger than grains of sand) are selected along cross-sections in different reaches in order to estimate the grain size distribution of the riverbed material. From this data, it is possible to estimate past flow conditions, specifically critical shear stress – the minimum force needed for flowing water to move a clast in a river. Coupled with drift line recordings and topographic cross- and longitudinal profiles of the riverbed, our team gained a dataset reflecting possible flood dynamics along the Selinus river. Drift lines indicate high flood levels. They are evidenced by litter that floats on the river and is left in the trees above the riverbed during floods, for example.

As the studied area appears to be much less affected by today’s construction, the research may also establish the limits for potential floods levels that could affect Roman Pergamon. Classical pebble-by-pebble counting data is accompanied by iPad LiDAR scans, drone imagery, and Structure from Motion (SfM) photogrammetry.

Mapping with LiDAR and field walks

High-resolution LiDAR-derived digital elevation model (DEM) data provided the basis for mapping the Selinus riverbed and conducting a geomorphological survey of the terraces and slopes along the river.

In the field, the digital geomorphological data were verified through visits to fluvial and agricultural terraces, braid-channels, pools-and-riffles, and much more. Each feature may be indicative of past river dynamics and helpful in understanding modern changes.

The challenge of ongoing river reworking

One issue quickly emerged during the fieldwork: Active reworking of the modern river channel obscures traces of natural flow paths (Fig. 3) – an issue for research of the past well known from the Pergamon Micro-Region. These dynamics make it difficult to distinguish between semi-natural patterns and short-term reconfigurations. Most of the Selinus riverbed was excavated after the last major flood in January 2024. These measures began with the construction of the Kestel Baraj reservoir, which opened in 1988. Currently, much of the water from the Selinus flows through a channel and tunnel into the neighboring catchment area.

Geomorphological mapping and detailed pebble counts may provide insight into flow patterns closer to those of ancient Pergamon than to the patterns seen today. Insights into the past were obtained through percussion drilling on fluvial terraces along the Selinus river. Hopefully, they will allow us to reconstruct flooding dynamics and establish a chronology of river dynamics.